India’s 500 and 1000-rupee notes are no longer valid currency

The waiting game at the banks

Last Tuesday in a bold and controversial move, Prime Minister Narendra Modi demonetised India’s two largest banknotes—those worth 500 rupees and 1000 rupees. Suddenly these bills—worth about A$10 and A$20 each—were essentially worthless.

Modi took the step in an effort to curb the spread of ‘black money’ or the financial gains of corruption. Corruption is rife in India, involving politicians, public servants, business people—virtually anyone who thinks they can get away with it.

The Prime Minister is so determined to halt corruption that he made the decision in secret, not even informing members his cabinet or other high ranking government officials. Clearly he did not want them offloading any of their ill-gotten gains.

We were in a homestay near the village of Koppe when the news broke, and luckily Anand and Deepti heard the broadcast as it aired.

Here was the deal. As of midnight on the Tuesday, all 500 and 1000-rupee notes were no longer valid currency, although they would be accepted for some transactions and for exchange until 31 December. Hospitals, fuel outlets, tourism sites and the like were urged to continue to accept 500-rupee notes or credit cards. All banks were to be closed Wednesday and Thursday.

The honest wait to change their banknotes

Modi made it clear he was not out to disadvantage the poor and honest, but was keen to eliminate the huge stashes of money acquired through corruption.

Starting on Friday, people (including tourists) would be able to go to a bank and exchange 4000 rupees worth of larger notes per day (ID would be mandatory).

Anand and Deepti did the sensible thing on the Tuesday night, and drove into Koppe and withdrew the daily limit of cash. They were hoping the ATM would give them a mix of 100s and 500s, which it did.

I wasn’t particularly concerned for us. Anand and Deepti make it easy for their travellers. The trip is prepaid and virtually all-inclusive, so all our accommodation, meals, admissions, transport and such are already covered. We pay for souvenirs, special drinks, any extra excursions we choose and some tips.

Plus, I am a hoarder of change—more about that later—so even though we had about 20,000 in 500 and 1000-rupee notes (about A$400 or US$308), I had another A$40 in small bills. That would be more than enough to carry us over until the banks reopened on Friday.

I now have heaps of change—a discontinued 1000-rupee note topped by 100 brand new 10-rupee notes

There was overwhelming handwringing and complaints in the aftermath of the announcement. As an example, taxi and auto rickshaw drivers had to decline fares because prospective customers waved only 500-rupees note at them. The same was true at small food stalls and other small operators. The buyers had small change, but didn’t want to part with it. The reality was that the announcement caught everyone unawares so these sellers simply did not have enough change to cater for so many requests.

But change is an issue most of the time, and especially for small operators. More than a week before the announcement was made, Poor John got a pair of shorts mended at a tailor’s in Goa. The fellow asked for 30 rupees (60 cents). Poor John had notes of 10, 100 and 500. The tailor chose to accept 10 rupees as payment rather than make change for a 100.

But back to the demonetisation.

We had a stroke of luck. Because of the outcry, there was a last minute decision to open banks on Thursday. This news was not widespread. In fact, we were surprised to find Koppe’s small bank open after we finished a morning safari drive on Thursday. (By the way, the jerk at the safari ticket office that morning wouldn’t take 500-rupee notes even though tourist outlets had been urged to do so. I could have slapped the smirk off his face.)

Anyway, Anand, Deepti and Poor John sashayed into the bank with photocopied IDs for the four of us. The bank’s photocopier wasn’t working, so a person couldn’t exchange notes unless they had their own photocopy (which the bank kept). Marian only had her passport, but no photocopies.

There were only about five people in the queue waiting to exchange notes, so the whole process went very quickly. The bank was already running low on cash, so only let each person exchange 2000 rupees.

Huge lines at banks

In an effort to exchange a share for Marian, we drove to the only Xerox shop in town (to get Marian’s passport photocopied) but it was closed. Then it turned out Sandeep (who doesn’t speak much English) got the gist of the conversation and produced a photocopy of his own ID. So in the end, we got 10,000 rupees worth of notes changed with little hassle.

Oh wait, there was a slight hassle. While Marian and I sat in the van waiting for the others to finish the banking, a policeman stopped and asked where the driver was. He said he’d noticed that our van had driven up and down the street four or five times that day and wondered what was going on.

Now Koppe isn’t a big place, but at one end of town are entrances to two stretches of vast wildlife parks. Out the other end of town are many kilometres of homestay places that cater for the tourists—Indian and foreign—who come to visit the parks. I suspect all tourists travel back and forth on that road all the time.

That said, I was so very tempted to tell him they were inside robbing the bank instead of exchanging the large rupee notes.

More waiting to change banknotes

It’s now a week later and we haven’t yet had a chance to exchange our large notes. We managed to spend a few in the first days, but now no one will take them. The queues at the banks have been overwhelmingly long—virtually thousands of people are waiting as we drive by.

ATMs are now dispensing only 100-rupee notes and a new 2000-rupee note has been released. A new 500 note is planned and the 1000 is to be scrapped completely.

Today Deepti found an ATM in a small town that was working and had only one person in the queue. Cash-wise Poor John and I are still fine.

Other people haven’t been so lucky! As of Saturday, quite a few banks were being investigated for exchanging large sums of notes without getting IDs, and up to 600 jewellers are under suspicion for taking large payments for goods.

Ah, the corruption continues.

One of the reasons I hoard change

I’ve hoarded change and small bills ever since I lived in Egypt in the 1970s. Shopkeepers loved saying they didn’t have change, so unless you had exact change you were usually out of pocket and sometimes by quite a bit. As a creature of habit, I still accumulate change.

It served me well in Burma in 1986 when U Ne Win demonetised the Burmese currency. He instantly withdrew all the 25, 50 and 100-kyat notes. A huge change given that an Australian dollar was worth 6 kyats.

And guess what? His astrologer advised him on good replacements, so we ended up getting 15, 35 and 75-kyat notes. Did wonders for our multiplication tables.

These rupee notes were not affected

When our host at the homestay near Koppe suggested that we set out at 5am and go for an hour-long drive/hike to see a sunrise from a hill, I was rather ho-hum about the whole thing.

In our extensive travels, we’ve seen scores of sunsets in scores of countries, and only a few have ever really impressed. Perhaps you have noticed that I only occasionally post sunrise and/or sunset photos.

So we put the option to a vote. Anand said he’d drive for those who wanted to do the sunrise, and Deepti said she’d lead a walking tour for those who wanted to bird-watch. Sleep was also an option, but no one ever chooses that.

Marian and Deepti take a closer look

Marian’s argument tipped the balance. She so sensibly said, I’m doing the sunrise. It’s probably the only time in my life that I’ll have the chance to see the sun come up over this valley.

She had a point. We’d be aiming for a hill in the Nawallakulaguda district of the Western Ghats, the mountains that run down the southwestern side of India. We’d drive for 30 minutes or so and then pick up a guide, Monappa.

He’d show us the rest of the way by road, and then lead us up an unmarked path to the top of a stony hill and the best viewpoint.

When we got out of the van at the base of the hill, I looked to my right and saw a small slice of clouds billowing below us. Hey, look at this everyone, I said, but Monappa (who spoke no English but understood Hindi) indicated that we were to hurry up before we missed the best bits.

Poor John and me in the Western Ghats

So on we trudged. By then, it was 5:50 and still on the chilly side. It took just short of 20 minutes to reach the top, and one of the most remarkable views I’ve ever seen.

The hill itself was a mix of intricate colours and textures, but there before us was the breathtaking spread of clouds shrouding the valley below.

The pictures can never do the scene justice, but I share them here for your enjoyment. The sunrise itself was lovely but pretty much unremarkable, but the sea of clouds dotted with close and distant hills was magical. Add temple music that started to play somewhere below about the time the sun started to appear, and we had the perfect start to a new day.

Monappa enjoys the view

It must be one of Monappa’s favourite places. Soon after we reached the top, he went to the edge to sit for a few minutes so he could enjoy the sweeping views.

The only cloudy sunrise I’ve seen that rivals this one was about 55 years ago. My dad flew a DC-3 and, as a child, I was often allowed to accompany him. One morning we took off to the east well before sunrise.

Below us was a thick blanket of clouds. I was sitting in the cockpit when the sun lit the clouds from below—flashing red, orange, gold, pink and purple, along with flashes of white. No camera back then, but my mind’s eye remembers it well.

To quote a line from Rudyard Kipling’s poem ‘Mandalay’—the dawn comes up like thunder.

Everyone wants their picture taken in front of Bibi Ka Maqbara

The Taj Mahal in Agra is, without doubt, India’s most visited tourist attraction. It’s the mausoleum that Mughal emperor, Shan Jahan, built to honour his beloved third and favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal, who died while giving birth to their 14th child.

With that childbirth record, she deserved an Eiffel Tower and Empire State Building as well, but the truth is that few buildings in the world match the beauty of the Taj Mahal.

Poor John and I have been lucky enough to visit to the Taj twice. You can read about our most recent visit here.

Looking up at Bibi Ka Maqbara

Decorative plaster work at base of pillar

This year, we had the chance to visit the Taj Mahal’s lookalike in Aurangabad, Maharashtra. I have known of this clone for several years, but have never been in the ‘neighbourhood’.

Bibi Ka Maqbara (or the Tomb of the Lady) was built in the 1650–60s by Azam Shah, son of Aurangzeb. It honours the memory of his mother, Dilras Banu Begum. Posthumously she was known as Rabia-ud-Daurani.

It’s not surprising that the two mausoleums are so similar in appearance. Mumtaz Malah was Azam Shah’s grandmother. On top of that, Bibi Ka Maqbara was designed by Ata-ullah, the son of the man who designed the Taj.

Bibi Ka Maqbara was originally supposed to rival the Taj, but budget constraints left it smaller and much less lavish.

Unlike the Taj, we were able to take photos inside this mausoleum. Rabia-ud-Daurani’s tomb is on the lower level at the centre of the hexagonal-shaped main building. It’s covered with an embellished cloth that is further decorated with many coins and banknotes, and the odd scrunched up entry ticket.

The tomb at Bibi Ka Maqbara is covered with coins, banknotes and paper scraps

Marble for the mausoleum was brought from Jaipur, more than 1000 kilometres away from Aurangabad. According to gem merchant and traveller, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, when he journeyed from Surat to Golconda, he saw 300 ox-drawn carts hauling marble to the construction site.

The compound includes an arched, rectangular mosque built by a Nizam of Hyderabad. It can accommodate almost 400 people for prayers.

We spent more than an hour wandering around the mausoleum, its expansive platform and the surrounding gardens. The whole compound is surrounded by a wall and overlooked by hills.

While Bibi Ka Maqbara may not outshine its inspiration, the Taj Mahal, it is a very fitting tribute to any mother.

Hills overlooking Bibi Ka Maqbara

Mum shapes potato cakes with son beside her

On the day that million of Hindus in India celebrated Diwali, the annual festival of lights, six of us piled into the Overland Expeditions India van and headed south through the state of Maharashtra to Tarkarli Beach.

Departure was around 6:15am. We had 300-plus kilometres to cover and plenty of dismally poor roads ahead. We’d get breakfast along the way.

Most of our travels have been away from India’s main highways, so our en route breakfasts and lunches have often been at roadside stalls, hole-in-the-wall eateries and government-managed rest stops.

Open-air kitchen at Mauli Snack Corner

But this morning, we were on very quiet back roads with not a paratha or chai in sight. This wasn’t because it was a holiday—just because there was a landscape of crops everywhere.

About 8:30am and just as we were about to dig into the communal bag of not-at-all-healthy snacks, we came upon a small food stall next to a field of sugar cane. We were 11 kilometres past one village and 35 from the next.

We ditched the snack bag as Anand pulled over to the side of the road.

There were other customers—some had arrived on bicycles and others on motorbikes—and they jumped up to offer us seats at the plastic table.

Vada pao

The compulsory group shot everywhere you go in India

We ordered a round of potato cakes (the only dish she was making at the time) and a round of chai.

Each cake (vada) was served in a bun (pao) with a good sprinkling of a chilli powder mixture. It may not be to everyone’s taste, but this is my kind of savoury breakfast. Oh, and I skipped the bun. I get enough bread anyway.

The potato cakes were so good that we ordered a second round, which our hostess shaped and fried in just a few minutes.

Small cups of milky chai came next, and I have to say that it was the nicest chai I’ve had on this trip. Just the right amount of spice and sugar. That’s a huge recommendation, given that I don’t normally add milk or sugar to coffee or tea.

The food stall is called Mauli Snack Corner, but I never got the name of our hostess/chef. Mauli is a common business name in India but not a woman’s name. I did learn that she opened the stall about two months ago, selling packaged and homemade snacks. It’s her enterprise, but her husband and son help. She said that business has been pretty good. It’s not surprising with such good food, and in a remote location that has good traffic.

She was quite modest about it all, but quick to say that she was especially proud that her son was doing well in his middle form English school.

All that said, I wonder how quickly she is making a living. Each vada pao (potato cake with bun) cost 10 rupees (about 20 Australian cents) and each cup of chai cost half that. So breakfast for six was a grand total of A$2.70.

Mauli Snack Corner in rural Maharashtra, India

A service station all dressed up for Diwali

Beginnings of an elaborate rangoli

Note: I tried to post this yesterday, but couldn’t get a stable connection. Diwali officially started Sunday.

As of yesterday, India is in the midst of celebrating Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights and one of the happiest and most important holidays of the year for Hindus all over the world.

Wherever Diwali is celebrated, you will see millions of candles, lamps and party lights twinkling from rooftops and verandahs, outside doors and windows, at temples and businesses, through whole communities—even trucks and tractors get the works.

Dad buys flowers for his daughter’s hair

Accompanying the lights are floral displays, colourful decorations, rangoli (chalk designs), new clothes, copious amounts of food, fireworks and blaring music.

Spiritually Diwali signifies the victory of light over darkness, good over evil, knowledge over ignorance, and hope over despair. It is a time to worship Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity.

Other religious significance attached to Diwali varies regionally within India, depending the local school of Hindu philosophy, legends and beliefs. Most use the day to honour the return of Lord Rama, his wife, Sita, and his brother, Lakshmana, from 14 years of exile after Lord Rama defeated Ravana. Diyas (lamps and candles) help to illuminate their path home.

I read today that for the first time ever, an American president, Barack Obama, honoured Diwali by lighting diyas in the White House.

This is the second Diwali we’ve enjoyed in India in the last three years. The first we spent camping just outside Pench National Park. That year, Deepti convinced us to buy party clothes at a shop called Bombay Dyeing in Jabalpur.

The poor salesman was completely flummoxed trying to find anything that would fit across my bosom. As a result, I spent rather too much time in the dressing room calling out for someone to come help me get out of yet another ‘straitjacket’.

At last, he came up with an almost florescent, multi-coloured frock with bright skin-tight blue leggings and a red and blue chiffon scarf—a fetching combination that would do well as a Halloween costume. Just add a mask!

My Diwali dress had more colours than this rangoli

I won’t be showing any pictures of that get-up unless Poor John wants to slip an image to fellow blogger, Brian Lageose, who writes hilarious dialogues to accompany often disturbing vintage photos.

Luckily, this Diwali was different. We had an epic 300-plus kilometre drive from the backwaters of Bhigwan (east of Pune) to Tarkarli Beach on the Indian Ocean.

This time we wore everyday clothes, and Anand drove 13 hours, with few breaks, through beautiful rolling countryside and then down a section of the Western Ghats (mountains).

All the cities, towns and villages were festooned with Diwali lights and decorations.

We were surprised to discover that Diwali doesn’t necessarily mean a day off for many people. Roadworks were underway in many places, and most businesses and shops were open. Poor John could even have had a haircut.

The celebrations for Diwali actually carry on over four or five days. Decorations are still up and the festive spirit remains.

By the way, Diwali goes by other names, especially Deepavali. It is observed worldwide by Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs.

Decorations for trucks

If you’ve never seen this holiday celebrated, maybe you should keep a lookout in your own country. In addition to India and Nepal, the main countries observing Diwali/Deepavali are Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Ireland, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, the Netherlands, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Suriname, Guyana, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Bhutan, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Mauritius.

Oh, and this holiday is not without its tragedies. The news this morning said there were 173 major fires reported yesterday, all caused by fireworks.

Firecrackers for sale in Malvan, near Tarkarli Beach

Two days ago, a major blaze swept through the firecracker market in Aurangabad (the city we had just left). More than 150 cracker stalls were destroyed, along with 40 vehicles (mostly two-wheelers). Thank goodness, only four people were injured.

But going back to that tight-fitting, eye-smiting Diwali dress I wore in 2013. It reminded me of the low-cut black velvet dress I made for a university dance in the late 1960s. It was the longest night of my life. I’ll get around to that story one day.

P.S. It’s been almost impossible to capture pics of the Diwali lights at night. I don’t have a tripod with me and the van travels too fast to get sharp pics. So most of the pics here are of the colourful and often intricate chalk decorations called rangoli.

Round rangoli

Simple Diwali decorations

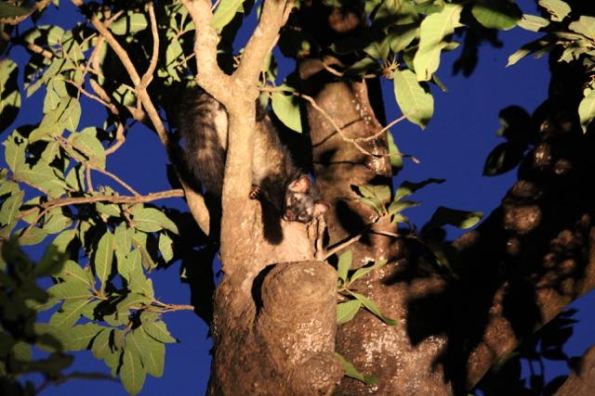

An Asian palm civet peers at us

The palm civet makes ready to go

We’ve had the chance to do a couple of night drives in the buffer zones that surround a few of India’s national parks.

The core areas of the parks close at sunset, but the buffer zones, which encircle most parks, remain open 24 hours. They have to because villages are often located in these zones.

So it was a treat on our first night near Satpura National Park to have a longish (almost two hours) night drive. We piled in an open-air Gypsy (small four-wheel drive) and bounced along dirt roads, with Anand and the driver using powerful torches (flashlights) to see what was around.

Wild boars trotting into the distance

Our first glimpse was of an Asian palm civet. It was high up in a tree—no idea how the fellows managed to spot it. Luckily it sat still long enough for me to snap a pic.

Then there was a troop of wild boars, followed by an Indian owl, an Indian hare and a nightjar.

The big bonus was several sightings of jungle cats. I even managed to photograph one.

We’ve had a few other fruitful night drives, but none that yielded any decent (meaning even remotely in focus) photos. But that said, we have seen snakes, a mongoose, another palm civet, spiders and more.

I promise to share more pics from night drives when I’m lucky enough to capture them. 🙂

A big thank you to Ben Vang

And a big shout out of heartfelt thanks to Ben Vang of Camera Check Point in Dubbo, New South Wales. Ben cleaned and serviced several camera lenses for me—especially the telephoto—which has allowed me to get some of these closer-up shots. If you are anywhere in Australia, I can highly recommend Ben’s services.

Jungle cat

The main gate at Sanchi’s main stupa

Approaching Stupa 1 at Sanchi. The heat is already setting in and the glare is intense

The Great Stupa at Sanchi is the oldest stone structure in India and we were lucky enough to visit it on a day trip from Bhopal.

Buddhist emperor Ashoka, often thought to be India’s greatest ruler (more about him another time), commissioned the original stupa during the Mauryan period in the 3rd century BC.

The core was a simple dome-shaped brick structure built over relics of the Buddha. It was topped with a parasol-like structure (a chatra) that symbolised high rank and served to honour and shelter the relics.

History says that Ashoka’s wife, Devi, oversaw construction of the stupa. She was born in Sanchi, and it was where she and Ashoka married.

We headed to Sanchi early in the day, so arrived well before the hottest part of the day and the arrival of most of the visitors. The place gets a lot of traffic. It is considered sacred, plus it has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1989.

The view of Stupa 1 from the monastery

Stupa 3 just near Stupa 1

During the Shunga period (2nd century BC), the stupa was expanded (or possibly vandalized and rebuilt) and the bricks were covered with stone. A century later, four elaborately carved toranas (ornamental gateways) and a balustrade encircling the entire structure were added.

We walked around the stupa on the upper level and visited all the gates, which mark the cardinal points of north, east, south and west. The main gate is on the north.

Although made of stone, the gateways were carved and constructed as if they were made of wood. They are covered with narrative sculptures.

These show scenes from Buddha’s life integrated with everyday events that would be familiar to onlookers and make it easier for them to understand the Buddhist creed as it applied to their lives.

At Sanchi (and many other stupas), the local population donated money to embellish the structure and to gain spiritual merit. There was no direct royal patronage.

South gate at Stupa 1 overlooking old monastery

Detail at the main gate

More detail at main gate

Devotees, both men and women, who gave money towards a sculpture would often choose to have it done as their favourite scene from the life of the Buddha and then have their names inscribed on it. This is why there is often repetition of particular Buddha episodes on the stupa.

But with the decline of Buddhism in India, the Sanchi monuments went out of use and fell into a state of disrepair.

In 1818, British officer General Taylor of the Bengal Cavalry recorded a visit to Sanchi. He was the first known Westerner to document (in English) the existence of Sanchi. At that time, he found the monuments to have been left undisturbed for a long time and generally well preserved.

Unfortunately, after his discovery, amateur archaeologists and treasure hunters ravaged the site until 1881, when proper restoration work was begun. Between 1912 and 1919, the structures were restored to their present condition under the supervision of Sir John Marshall.

Today, around 50 monuments remain on the hill of Sanchi, including three stupas, several temples and the remains of a monastery.

Stupa 2

We visited as much of the sie as we could find, including Stupa 2, which was way farther down the hill than we expected. Never mind, we got in our exercise for the day. The collage of pics above show some detail at Stupa 2 and the steps to it.

Oh, and if you’re in to numbers, the main stupa is 12 metres tall (54 feet) and 32 metres in diameter (120 feet). The others are much smaller.

One of the temples at Sanchi

A view of the countryside below Sanchi

Romance was in the air today!

It all started this morning at Pench Tiger Reserve in central India. We’ve had numerous safaris through Pench over the last three years, but today was the first time we’d ventured to a distant end of the reserve.

That’s when we saw her, strolling along the road enjoying the solitude of a chilly morning. Within seconds she spotted us and bolted into the bush before we could get a pic. We raced forward in the Gypsy (small four-wheel drive) to where she’d vanished, but she was now just a blur in the scrub. We lingered a while, hoping she’d gather courage and reappear, but nope.

As we were about to give up and turn back, he came in to view, padding toward us, yet not seeing us.

It didn’t take long to figure out he was a man on a mission. He zigzagged back and forth across the road, sniffing the ground, the grasses and the air. Ah, yes, he was on her trail.

And for the next 70 minutes we watched poor Albert (I’ll soon explain why I’ve called him Albert) do his best to lure her out of hiding.

He sniffed and scratched, piddled and sprayed, and sawed. Male leopards make the most extraordinary bellowing when they are trying to call a female to them. It’s called sawing and that’s because it sounds exactly like someone cutting down a tree with a handsaw.

Anand and Deepti say it is most unusual for leopards to linger in plain view for as long as Albert did. They are naturally skittish and a sighting of a minute or two is considered a long viewing.

But Albert had only one thing on his mind, and it wasn’t us. So we were left to follow him for as long as he stayed within view. He roamed back and forth across the road, scratched trees and sat on rocks to saw pitifully.

Either the girl was far away by now, or just not interested. His woeful sawing reminded me of another Albert, a likeable yet semi-tragic figure who graces some of the stories on Fifty Words Daily.

I hope both Alberts end up getting the girl.

As for us—it was the most remarkable leopard sighting I will probably ever see.

P.S. I took about 200 photos in 70 minutes and it’s been hard to choose the ones to share. Plus I had to rush before the lodge turned off the internet—my first connection in a week. I may be compelled to share more later. 🙂

Adam and Eve of the Baiga tribe. Part of a display in Bhopal’s Ethnic Museum explaining how the earth came to be.

Today was an eye-opener for me.

So far, we’ve had four days in India. Twelve hours between flights were in New Delhi—a city we know fairly well—and three days have been in Bhopal—a city I first met in the news in the 1980s.

Too many people will remember Bhopal for the tragic chemical gas leak and explosion that happened 32 years ago, just after midnight in December 1984.

Almost 4000 people have died as a direct result of the disaster and more than half a million were affected. It’s often called the world’s worst-ever industrial disaster, and it never should have happened. Even today, there is a general view that Union Carbide has never really paid its dues on this matter.

Thankfully Bhopal has gone on to recover, grow and prosper.

But that hasn’t been my eye-opener.

After four days in India, I realised I haven’t shared anything with you.

I’ve looked, liked and/or commented on blogs I follow. I’ve plowed through several hundred emails and still have 50 unviewed and another 22 that need answers. I haven’t written to my kids except to say we arrived safely.

And most of all, I haven’t told you a darned thing about all the amazing things we’ve seen.

This is worrying, especially when the internet connection drops out regularly and each page takes several minutes to load.

Part of the Bada Gumbad Complex in New Delhi’s Lodi Garden

When I said I was heading to India, fellow blogger and excellent photographer, Vicki Alford, told me to ‘forget’ about dealing with all the online stuff and enjoy the travels.

So I’m taking Vicki’s advice seriously. I’ll try to post as often as I can about where we are and what we are doing. But just for the time being, I am going to stop worrying about liking, following or commenting on other blogs.

Internet connections in the big city have been slow and unreliable. In an hour we head into Satpura National Park and connections will get worse or non-existent. Hey, this post took about six hours to get loaded.

Hope you’ll understand that for now, I’m going focus my patchy internet time on sharing India with you.

P.S. In the last few days we seen vast gardens, multiple festival celebrations, two mosques, a fort, two museums (including the most amazing ethnic/tribal museum I have ever seen), two scenic lakes, traffic jams like you wouldn’t believe (because the Prime Minster was visiting Bhopal), and a hairdressing salon, where three of us gals got the works.

P.P.S. If you are interested in knowing more about the gas disaster in 1984, I can highly recommend the heartbreaking Five past midnight in Bhopal by Dominque Lapierre and Javier Moro.

P.P.S. Don’t forget to check out my cooking blog. Here’s a great Indian recipe for spinach and lentil dal.

Overlooking Bhopal and one of its lakes

Poor John and I are about to board a flight to Singapore, with a final destination—many hours from now—of India.

Looking forward to 45 days of road trip in India’s south with the young naturalists we have travelled with twice before. It’s mostly about the animals—lions and tigers and bears. Yes, India has all three—Asiatic lions, Bengal tigers and sloth bears. When we aren’t exploring, we’ll be enjoying the wonderful cuisines of India.

Obviously, I’ll have a lot less online time, so forgive me if I miss liking or commenting on your blog posts. I’ll do my best. We’ll be travelling remotely a lot of the time.