Evert Taube, Sweden’s foremost musician, with Stockholm City Hall in the background

Looks can be deceiving and that’s just what Ragnar Östberg set out to do when he designed the iconic City Hall for Stockholm, the capital of Sweden.

Östberg, who won a competition in the early 1900s to create a new city hall, reworked his original designs throughout the entire construction period.

For starters, he added a 106-metre tower, which had been part of the original plan offered by Carl Westman, who came second in the competition. The top of the tower features three crowns from the Swedish coat of arms. He also added a lantern at the top and ditched his plans to have blue glazed tiles in what is still called the Blue Hall. That’s where the annual Nobel Prizes (except for the Peace Prize which is awarded in Norway) are awarded in December of each year. The organ in the Blue Hall, with its 10,270 pipes, is the largest in Scandinavia.

Internal courtyard

Stockholm City Hall with tower

Many of Östberg’s tinkerings were done to make the structure look older than it really is. The eight million dark red bricks used in the construction are ‘munktegel’ (or monk’s bricks) that were traditionally used in the construction of churches and monasteries. After the bricks were in place, Östberg decided it was a good idea to have each brick roughed up so they looked more weathered. All that was done by hand, and contributed to a huge budget blow-out.

The columns in the arches are mix and match, reminiscent of times when materials from old buildings were removed and used in new ones.

Östberg’s efforts seem to have paid off. Our guide asked people in the group to guess how old the city hall was (we’d already read that it opened in 1923) and most of them speculated around 400 years old.

The overall design mixes several styles, blending North European, Venetian and Middle Eastern elements. The building surrounds internal and external courtyards, and overall is very effective.

Golden Hall, far wall

The highlight is the Golden Hall, named after the decorative mosaics made of more than 18 million small tiles. Our guide explained that the gold is 24-carat gold, but pounded so thinly that only about 10 kilos of gold was used in making all of them. The mosaics, designed by artist Einar Forseth, show people and events from Swedish history and legend, as well as images from the rest of the world. The room is 44 metres (144 feet) in height.

Stockholm’s city council has 101 members—50 women and 51 men. The head of the council is a woman. The balance changes regularly. The previous council had 51 women and 50 men, with a man as the head.

Because the City Hall is a functioning government and administrative centre, you can visit only by guided tour. These run every hour and are offered in English and Swedish (and perhaps other languages by appointment). Certainly well worth a visit.

By the way, the City Hall is built on a place once occupied by an old mill, Eldkvarnen, that burned down in 1878.

Oh, and I should mention that one of the hallways has murals painted by the then prince. It took him five years and he was a bit fed up with the whole thing when he was done. Sorry there are no photos of it, but the sun cast such long shadows, I couldn’t do any of the panels justice.

A 1:10 model of the Vasa as she looked when first built

You might not have noticed, but we slipped away from France to visit Finland and Sweden for 12 days. It’s been a great detour and I have lots of stories to share, especially about Finland where we spent most of the time.

But first a couple of posts about Sweden and some highlights of its capital, Stockholm, in particular.

Poor John had the Vasa Museum at the top of his must-see list. It’s home to the 64-gun warship Vasa that sank in the Stockholm Harbour in August 1628 on her maiden voyage. It’s the only almost fully intact 17th century ship that has ever been salvaged.

The museum opened in 1990, and according to its website, it is the most visited museum in all of Scandinavia. It’s easy to see why.

The Vasa sank in 1628 on her maiden voyage

We paid our admission and walked into the main hall to be instantly overwhelmed by an entire ship that was lifted from the sea after being under water for 300+ years.

How she came to be in the museum is a wonderful story.

In the 1920s, a group of divers applied for a permit to find the wreck and blow it up so they could salvage the valuable black oak timbers. That didn’t happen and in the 1950s, a private researcher, Anders Franzén, began to search for the Vasa. He was confident that she had survived in the brackish waters of the Baltic Sea. In salty water, wood is rapidly destroyed by shipworms.

Franzén found her by chance in 1956. For a couple of years, he had avoided searching an underwater mound because he’d been told that’s where great piles of stones had been dumped years earlier. When he learned the stones had been dumped elsewhere, he and Navy diver, Per Edvin Fälting, immediately rowed out to the mound. A sampler brought up pieces of black oak. Fälting then dived down and found the ship’s hulk and cannon ports.

The Vasa’s stern

The Vasa’s bow

It took almost two years and amazing engineering feats to raise the 700-ton ship, but she was brought up in one piece in 1959. This was done by digging six tunnels under her and then threading through six-inch cables that were used to gently lift her from the mud and sludge. After another two years, she was shifted into dry dock, having been put afloat after 333 years. In all, the Vasa was allowed to dry for nine years, with about 500 tonnes of water evaporating away.

A cross-section model shows how little ballast was at the bottom of the Vasa

So why did she sink in the harbour on her maiden voyage?

To make a very long story short, she quite simply was built with the wrong proportions. Too long, tall and skinny to carry enough ballast to keep her upright. She need a deeper and wider hull. It took only a light squall to send her over and down.

When she sank, the Vasa had a crew of 445—with 145 mariners and 300 soldiers. It’s estimated that 30–50 died when the ship went down. It was interesting to see displays of how they might have dressed and see possessions that have been retrieved from the deep.

The museum has excellent descriptions—in Finnish, Swedish and English—of the ship’s history, including how she was built, decorated and, ultimately, renovated and repaired.

Her hull is comprised of thousands of timbers, held together by about 30,000 original treenails and 5500 steel bolts inserted after she was salvaged. Some these bolts are 2 meters long and go through the massive hull. These bolts are rusting and are being replaced by stainless steel equivalents.

A quick comment about the ship’s sculptures and carved ornaments. There are 500 of them and historians did their best to match the original colour schemes. Research on colours was conducted over 12 years and involved more than 1000 pigment samples (see the pic of the final colours used).

The sculptures were a tribute to the king, Gustav II Adolf. They were also a reminder to the people to live up to the king’s virtues of piety, courage and wisdom. One of the largest is the shield with three crowns, which has been part of the Swedish coat-of-arms since the 14th century.

Also, there is a 1:10 model of the ship, which depicts the Vasa when newly built and with all 10 sails set. The model measures 6.93 metres long and 4.75 metres tall.

Shield with three crowns

Sculptures including shield with three crowns

View of the nave and to the pipe organ (see scaffolding on left)

The Basilica (Cathedral) of Saint-Denis in Paris has a wonderfully creepy story of how it came to be where it is. In the 3rd century, Saint Denis, a patron saint of France and the first bishop of Paris, and two of his followers were beheaded on the hill at Montmartre. The legend goes that Saint Denis, carrying his own head, then walked to the site of the current church and indicated that’s where he wanted to be buried.

A special church (a martyrium) was built on the site of his grave and became a popular pilgrimage destination in the 5th and 6th centuries.

Towards the altar (also called choir)

Now I won’t go into all the building, rebuilding, renovations and expansions that have taken place over the centuries, but I will say that the basilica (and its accompanying abbey) became a popular burial place for the royalty of France. In fact, it’s often referred to as the ‘royal necropolis of France’.

In fact, all but three of the French monarchs from the 10th century to 1789 have their remains at Saint Denis. But after the French Revolution, the ancient monarchs were removed from the church. Their bodies were dumped into mass graves and covered with lime to destroy them.

The north transept rose features the Tree of Jesse

In 1817, the ruling Bourbons ordered that the mass graves be opened and the royal remains be returned to Saint-Denis. By then, only a few parts of three bodies remained intact. The remaining bones from 158 bodies were collected into an ossuary in the crypt of Saint Denis. Today a marble plates bears their names.

Poor John and I spent more than an hour wandering around the church, admiring the sculptures and stained glass windows. A commenter below (Buying Seafood) reminded me that this church is considered to be the birthplace of gothic architecture, initiated by the Abbot Suger.

Some renovations are being carried out in the nave at the moment, so there wasn’t a completely clear view of everything.

After ‘doing’ the main part of the cathedral, which is open to the public at no charge, we even paid the 9 euros (each) admission to access the inner parts of the cathedral and the crypts below.

There are some amazing statues throughout the cathedral. A touching one is of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette praying. Another is the tomb of Charles V and wife, Jeanne de Bourbon. Still another tomb (for Louis XII and Anne de Bretagne) was capturing the reflection from stained glass windows. I got a couple of pics of it, and within minutes the sun had moved on and the colour was gone.

Students listen to stories about Saint-Denis and the cathedral

We got a kick out of the teacher/guide with a group of school children. We could only watch him from the back, but he was full of animation and the kids were spellbound. One was even videoing his ‘performance’.

By the way, keep your wits about you if you decide to visit the cathedral. Libby and Daniel warned us that Saint Denis is in a rough neighbourhood—not as rough as it used to be, but still requiring caution.

I carried my camera in a small backpack, rather than in the normal camera case. And I didn’t bring the camera out when we wandered through the market that is almost directly opposite Saint Denis. That said, we never felt threatened or unsafe.

Final resting places including remains of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

Emile Zola, novelist

Paris is one of the few cities in the world that is famous for, of all things, its cemeteries. Last time we were here, we visited the catacombs, which aren’t exactly cemeteries, but are filled with the bones of thousands of Parisians long gone.

This time we headed to Montmartre with its famous church, the Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Paris (or the Sacré-Coeur Basilica), and the nearby cemetery, which is the final resting place for many famous artists who lived and worked in the Montmartre area.

Now before we get there, I have to have a little whinge about finding the entrance to the place.

I visited this cemetery in 2003, and I recall arriving at the gate without any difficulty at all. This time we walked around the entire perimeter and then back and forth over the Rue Caulaincourt viaduct that overlooks the entrance gate. The place seemed impenetrable and I began to think the only way in would be to abseil, but finally we noticed a small sign that pointed to a steep staircase that took us to ground level. If you’re ever in a similar situation, remember this address—20 Avenue Rachel in the 18th arrondissement.

Part of Montmartre Cemetery runs under Rue Caulaincourt viaduct

Anyway, on to the cemetery.

We spent ages trailing around the cemetery (map in hand), looking for famous graves and admiring the beautiful landscapes. The graves of unknowns—at least unknown to us—far outnumber the famous and many are quite beautiful.

I’ve included some pics of both here and, for the most part, only added captions for the famous.

Okay, I’ll admit it. I didn’t know who all the famous people were but the map told me why they were famous and I’ve added that too.

P.S. I’ll try to stop by Montparnasse Cemetery before this trip ends. And more to come about Montmartre, in general, and the basilica.

P.P.S. If you need a laugh check out the goat cheese torta recipe from my other blog. It’s from Being dead is no excuse: the Official Southern Ladies Guide to Hosting the Perfect Funeral.

A photogenic grave

A grand staircase in the Musée Carnavalet

Paris is overrun with museums, but few give you a true idea of what the city was like, say, at the time of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Luckily, the Musée Carnavalet fills in the gaps beautifully.

Housed in two townhouses in the Marais district, the Carnavalet is the city’s oldest municipal museum

We had the luxury of spending an afternoon there, exploring the more than 100 rooms that hold more than 600,000 items.

There are paintings galore showing scenes of Paris in bygone days, as well as countless re-creations of rooms in styles ranging from the 17th to the 20th century. Clocks were an important feature in every room, and I seem to have taken way too many pictures of them. Sorry!

Room occupied by Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette

Room occupied by Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette

One of my favourite displays was the re-creation of the Temple Tower rooms where Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette were imprisoned for about six months in 1793. Later royalists viewed the Temple Tower as a sign of the suffering faced by their royal family after the French Revolution. To keep the tower from becoming a destination for pilgrims, Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the tower destroyed in 1808.

The fact that the furnishings from those rooms still exist at all is thanks to donations and the estates of Jacques-Albert Berthélemy, an architect who lived in the tower, and Jean Baptise Cléry, the king’s last valet.

Fouquet’s extraordinary jewellery shop, designed by Czech artist Alphonse Mucha

My other absolute favourite was the gorgeous art nouveau shop owned by jeweller, George Fouquet.

The entire room is from the original jewellery store designed by Czech artist Alphonse Mucha in 1901. Fouquet donated his shop in its entirety to the Carnavalet, and it was reassembled as it was. It’s a small room brimming with colour and grandiose, a completely preserved Belle Epoque work of art. I could live in this space.

Some other special exhibits are a prince’s cradle and the cork-lined bedroom of French writer Marcel Proust.

Marcel Proust’s cork-lined bedroom

A prince’s cradle

A bit more about the museum and its two townhouses

The idea of a museum devoted to the history of Paris came about during the Second Empire (1852–70), when a large part of the historic heart of Paris was being demolished.

In 1866, at the instigation of Baron Haussmann, the city council bought the hôtel Carnavalet, which had been built in 1548, to house the new institution.

The museum opened in 1880. It has been extended several times and since 1989 it has also occupied the adjoining townhouse, hôtel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau, built in 1688.

P.S. I mentioned earlier that, in French, the word ‘hôtel’ often refers to a mansion and not an actual hotel.

The Orangerie des Tuileries in Paris seems destined to spend its life housing plants in one form or another. It started life in 1852 when it was first built to provide shelter for the orange trees that lined the garden of Tuileries Palace.

The trees mustn’t have lasted long in Parisian winters, because the Orangerie got side-tracked for several decades, serving different functions (such as an exam hall, exhibition hall and concert hall). Then in 1920 it was chosen to house a completely different type of plant—large painted panels known as Nyphméas or Water Lilies by French impressionist Claude Monet.

Over the last 30 years of his life, Monet focused on painting the water lilies in the flower garden at his home in Giverny. About 250 of his paintings feature these flowers (many were painted when Monet had cataracts),

But the Orangerie paintings were done especially for that location. They were considered such an important contribution to the setting that Camille Lefèvre, the architect in charge of the renovation, followed Monet’s instructions to the word when designing the two elliptical rooms that house the masterpieces to this day.

Lefèvre then designed the rest of the building to be an exhibition hall. I’ll write about that soon and share some of the images that are included in what is now known as the Walter–Guillaume collection.

But for now I’ll share some of the pics (including some close-ups of some panels) from the day we visited the water lilies. I haven’t added captions. We were lucky enough to go on the first Sunday of a month when many museums offer free admission.

P.S. Over the years I’ve seen many of Monet’s water lily paintings, but all of these were new to me.

P.P.S. I hope you like the Little Miss who features in many of my photos. She was taking in everything and seemed to pop up everywhere. I wonder if she’ll remember this day when she’s much older. Do you have childhood memories of seeing art exhibitions?

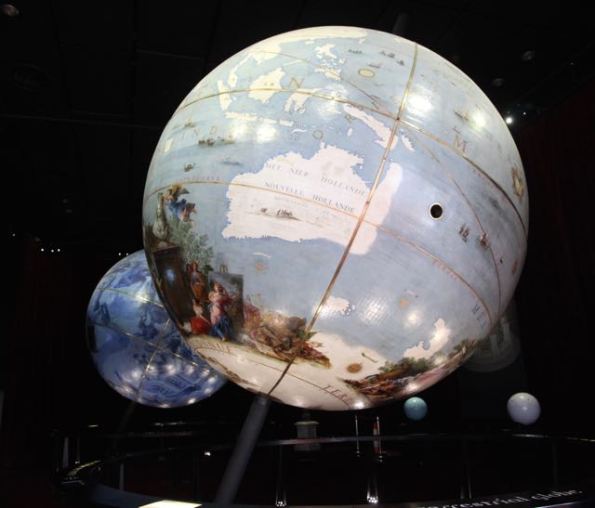

Australia is mostly there on Coronelli’s terrestrial globe

Two of the four towers that surround a one-hectare garden. I’m at the other end with my back to the other two towers

Our plane landed in Paris early Thursday morning and we were determined to stay awake as long as we could in order to set a new time routine. It seemed to be a challenge. We’d flown over eight time zones and were faced with the prospect of a cool and wet day in Paris. Luckily our daughter, Libby, presented us with a list of rainy-day activities to keep us occupied while she went to work.

Most listings were for museums we hadn’t seen before, but one destination offered the greatest temptation—the National Library of France.

Australia has a wonderful national library with regular exhibitions, so we dumped our bags, had a quick shower and some food, and headed out to explore part of the French equivalent.

Known officially as the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the library is composed of seven separate sites and we went to the largest, the François-Mitterrand Library, which opened in 1996.

It was fantastic to walk around the library, but the big bonus was the free exhibitions on display. The first to catch our attention was the Science for All 1850–1900. It covers the array of scientific subjects being studied during the last half of the 19th century.

The exhibit is pitched at high school age, so our French was good enough to make out most of the explanations. We got a kick out the drawing showing an experiment to see how electric shocks affected the body. The guinea pig was a woman, but all the spectators were men. Or perhaps she was in charge.

This exhibit continues until 27 August.

But two large globes were the most unexpected and rewarding exhibit we saw, and one that neither of us had ever heard of.

Venetian cosmographer Vincenzo Coronelli designed the globes in Paris between 1681 and 1683. Jean-Baptiste Corneille and Jean-Baptise Franquelin were two of the most important artists to illustrate them. One depicts the celestial sky with all the constellations known at the birth of Louis XIV. The other is terrestrial and gives a complete cartography of the world at the time (California is shown as an island).

The Cardinal of Estrées offered both pieces to King Louis XIV at the end of the 17th century.

Measuring measure 3.8 metres in diameter and weighing about 2 tons each, the two spheres are the most monumental pieces in the library’s collection. They have been in the collection since the 18th century, but were rarely shown until they went on permanent display in 2006.

We had the luxury of walking round and round both globes, but the lighting was low, which meant I couldn’t photograph all the angles. In fact, we initially thought they were copies of the originals but, no, we were looking at pieces created more than 330 years ago.

More about the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

The library itself is an unusual and impressive structure. It consists of four towers, with each representing an open book. The towers are connected by outdoor platforms, and surround a one-hectare garden. Architect Dominique Perrault designed the complex. He was selected at the end of an international competition organised in 1989.

If you’re a numbers person here are some of the stats. Each tower is 80 metres tall with 22 floors. There are 60,000 square metres of platforms, 57,000 square metres of book stacks, and 54,000 metres of reading rooms. The library holds 14 million documents or 400 linear kilometres of stacks.

Admission is free (except for a couple of special exhibits).

The celestial globe depicts the constellations

Graeme looks very tiny standing in front of castle Rock

The second day we were on Flinders Island, Graeme said we absolutely had to do the Castle Rock walk that started near Allport Beach.

He confessed that he’d only ever driven to Castle Rock, but knew that the actual walk was highly recommended as a top thing for tourists to do.

So off we set in the car. Flinders Island is 75 kilometres top to bottom and you pretty much have to have a car to get places.

The sign said it was an easy walk—3.3 kilometres one way and 1.5 hours to go and come back. We headed out on the trail and within about 300 metres came the sea of bowling balls.

Now picture this. I’m wearing thongs (I don’t know why the rest of the world has decided to call them flip flops?) and suddenly there’s about 50 metres of path that is a bed of round rocks of differing sizes, but mostly smallish.

The sea of bowling balls

Poor John has, as usual, shot ahead and Graeme is just starting to navigate this unexpected obstacle course. Get back here please, I said to Graeme, as I tried to step from ball to ball. I took off my thongs and took hold of Graeme’s arm. But two metres into the escapade, I surrendered.

No way I’m starting this holiday with a broken ankle! Graeme had to agree that he didn’t fancy struggling across. Poor John, of course, had made it to the other side and was disappearing around a corner.

Graeme and I back-tracked to look for a better path, but in the end gave up and decided to drive to Castle Rock.

Coming to Castle Rock from behind

As we headed to the car we met a family of four and told them what was ahead, saying them might find it problematic. We later learned they they also turned back.

So Graeme and I drove to Castle Rock, which is magnificent, and waited for Poor John. Graeme, who rarely feels the cold, also went for a swim.

Well guess what! It took Poor John a whole 1.5 hours to go one way, and he said the terrain got worse just after the bowling balls, and then got much, much better.

Poor John is out there somewhere

Poor John fitted in another short walk. When we got back to the car Graeme realised he’d left his keys on a rock where he went for the swim, and Poor John went back to get them.

That night we read an entertaining blog post by a woman who had done the walk with friends. One way took them three hours. On the way back, they found an inland path which cut the return trip to two hours.

In spite of all that, Castle Rock is really worth the visit, and I’d quite happily do the walk if I can ever find the way around the bowling balls.

By the way, we’ve heard that Flinders Island has received a million dollar grant to update their tourist signage. It will be a good investment.

Our whereabouts

We start another adventure today—France, Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and Belgium. Home at the end of June.

Poor John heads out to retrieve the keys

Tink almost snoozing

Just over a year ago, a video clip of Derek (or Derrick) the Wombat brought fame to Flinders Island, off the northeast coast of Australia’s state of Tasmania.

Guess what? Derek has grown up and moved into the bush. Teenage wombats can be quite aggressive. Nevertheless, he stops back at Kate Mooney’s rural home often and even lets himself in by the ‘dog’ door. April and May, two other orphaned wombats reared by Mooney, also drop by, but now Tink rules the house.

She—I think Tink is a she—in the latest resident at Mooney’s home, and we were lucky enough to go around to her place for lunch the other day.

I knelt down to photograph Tink and she scurried over to create her own ‘cubby house’ between my calves

Tink craves human contact and immediately endeared herself to us, snuggling between our feet and legs, and even attacking Poor John’s feet.

It was a real privilege to get to know this young beast and know that she’ll survive to rule the bush.

Mooney is often known as the Wombat Lady of Flinders Island. Her 40-hectare farm is a refuge for wombats that have lost their mothers, usually because they’ve been hit by a car. We were stunned to see how many wallabies and wombats on Flinders end up as roadkill on the island.

Thank goodness Mooney steps up to help some of them survive.

Here are two links to articles and videos about Derek and Mooney. You can find more on Google. You might also find a way to donate to Mooney’s efforts.

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-09/derek-baby-wombat-bringing-tourists-to-flinders-island/8338768

http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2016/03/derek-the-baby-wombat-melts-hearts

Tink thinks Poor John’s feet provide a perfect mattress