Fellow blogger, Cryptic Garland, recently did a post with a pic of a huntsman spider clutching her egg sac that most likely held a gazillion baby huntsmen.

It started a flurry of comments about Australia’s deadly creatures. We’ve got more than our share of snakes and spiders in the world’s top 10 most poisonous. And of course there are the sharks too.

We’ve hosted many exchange students and most of them come to the country terrified that they will encounter the ‘Three Esses—spiders, snakes and sharks’ probably all on the first day.

I always thought they should have been more concerned about liking school, making friends and fitting in with their host family. But I digress.

The flurry of comments didn’t make a single mention of the prickly critter I saw while walking the dog.

Lately I’ve been walking Indi, our standard schnauzer, around Lake Burley Griffin, a manmade wonder that graces the centre of Canberra, the nation’s capital.

It’s a gorgeous and popular place to be when the weather is nice. We see plenty of people and dogs, as well as an array of birds and bunnies, but Saturday was the first time we ever saw an echidna.

According to Wildcare Australia, echidnas are the oldest surviving mammal on the planet. Their page on echidnas is full of interesting info, so I’ll tell about our experience instead.

We got out of the car near one of the memorials scattered around the lake, and there it was trundling along with purpose. Of course, it was headed straight for the small road that runs alongside the lake, so Indi and I swung around in front of it in the hopes of directing it back towards the lake.

It did so obligingly and I was so proud of Indi (who was on her lead) for not barking or trying to torment the echidna in any way. In fact, we walked alongside it for 20 to 30 minutes, with Indi often sitting and gazing in wonder.

We kept a distance of about two metres and pointed the echidna out to all the passersby. It is rare to see them out in the open like this, and for many it was their first time seeing one ‘in the wild’.

One woman approached to say she had seen another one farther back along the path and had called the ranger to ask what to do. According to the ranger, this is the time of year when echidnas move about a lot and to not worry about them unless they are injured.

Our goal was to keep this one from getting in the road and getting run over, so our walk was aimed at getting it to a place much farther from the road.

The echidna had other ideas. About 20 metres short of where I hoped we’d get to, it did a 90-degree turn and headed straight for the road. By then about 10 people were crowded around. I think our little friend had had enough.

As we watched, nervous that it might tumble into the road, it instead started to dig itself underground. I had no idea echidnas could do this, and apparently when they do, there’s no way of getting them out unless you dig a huge hole around and under them.

One fellow realised this very quickly. The echidna had only just started to dig, when this guy took the pillow out of his kid’s pusher and tried to pick up the echidna. He couldn’t budge it. It was as if its feet had grown clamps.

So we all stepped back and watched it bury itself completely. Wow! I guess they really are solitary, and certainly not very scary.

Indi and I went back on Sunday to check on it, but the echidna had moved on.

If you’re in a hurry to move on, you might check out another one of our lakeside walks or a recipe on my cooking blog.

Africa is still one of my favourite continents. Both Poor John and I lived there for a few years, and spent many more remarkable months (in the 1970s and again in 2009) travelling through a swag of countries on the back of a truck.

So we were delighted to make a side trip to the Congo while we were in France last month.

You might not know that there are two Congos, There’s Congo Brazzaville (slightly more peaceful) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (known formerly as the Belgian Congo or Zaire).

Our brief side trip took us to the latter Congo (or DRC), which is also the more violent and war-torn. Civil war has raged there since 1996 and more than 5.4 million people have died in the conflict. That death toll is almost unbelievable and millions more have been maimed, raped, left homeless and all sorts of other travesties. If you don’t know much about the place, you can learn more here.

While the war continues to be heartbreaking and horrific, there’s much more to the country. We had a short but peaceful time there and a most amazing turkey sandwich, but more about that another time.

The Parisian side trip was all about art—especially art produced over the last 90 years. The artworks, which I hope will make an international tour, are currently on display at the Cartier Foundation in Paris.

The exhibit, called Beauté Congo, features 350 pieces by 41 artists. There are paintings, sculptures, photographs and even some music. Scattered amongst the artworks are music pods, where you can tune into music that reinforces the themes of the art pieces.

About some of the works

This is the first-ever retrospective of art from the DRC. Most of the pieces have never been displayed internationally, and have instead ‘lived’ in private collections in Belgium, France and Switzerland. Others have come from Belgium’s colonial archives, while a few others have come from the artists themselves.

While I never got pictures of this practice, it is common for DRC artists to hang their paintings outside their studios for all the world to see. This fits with the exhibition itself.

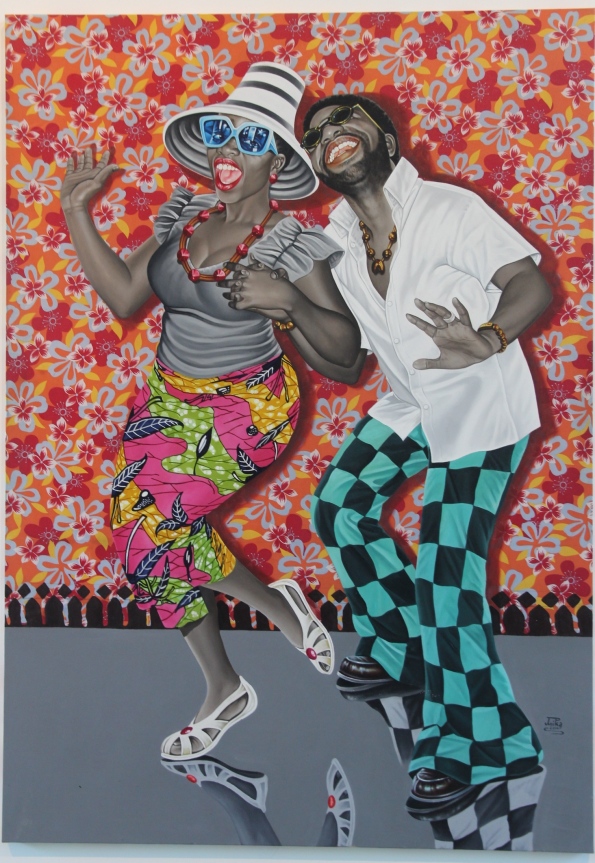

Many artworks reflected DRC’s street life—bars, music, dance, flamboyant clothes and cars. In fact, the exhibition’s vibrant main photo (and the one featured on the cover of the exhibition’s book) is of street dancing. It was Poor John’s and my favourite piece. It’s by JP Mika who was born in Kinshasa in 1980.

Several early artists had pieces that reminded us of Aboriginal art. They were by Sylvestre Kaballa, Mode Munta, Lukanga and Mwenze Kibwanga.

There were two interesting sculptures by people whose names I failed to catch. Sorry. I was sure I’d photographed the ID cards, but can’t find them now.

We really loved some of the ancient pieces from the Belgian archives. These included pieces by husband and wife, Antoinette and Albert Lubaki. The images are near the bottom of this post.

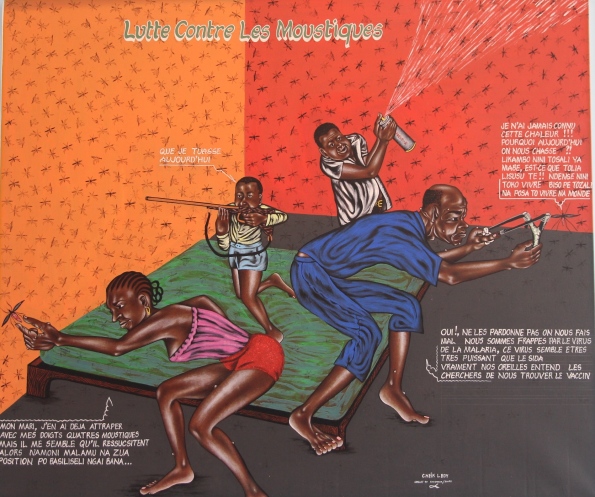

I also got a kick out of Cheik Ledy’s painting of the battle against mosquitos. He/she died in 1997 and I hope it wasn’t from malaria.

We spent longer at the exhibit than we’d planned for and have no regrets. The exhibit was supposed to end this month (November), but it’s been extended through January. Great decision.

Yes, we went shopping

There are two floors of works and another floor of sales. We actually got sucked into the sales, which is most unusual for us.

One purchase was an overview of the exhibit. After Paris, we were going to Belgium to stay with a friend who taught in the Belgian Congo for a couple of years. I knew he’d love the overview, so we bought it as a thanks-for-having us-stay-with-you gift. He loved it.

Our other purchase was one we dithered over. Poor John spotted it first—a not-so-slim volume of Kim Jong Il Looking at Things. It was a back and forth conversation.

I can’t really justify this, he said.

Oh for heaven’s sake, you’ll get a lot of mileage out of showing it to friends, I countered.

He thought for a nanosecond and bought it.

When we got back to Libby’s place, we showed it to her straightaway.

Her reaction, Oh thank goodness you bought it. I agonized over whether to buy it and finally decided not to.

I guess we know who gets it in the will. Maybe we should have bought multiple copies.

Our trip to Europe wasn’t all about art, galleries and museums. We managed to cram in villages, valleys, restaurants (of course), markets, wineries, landmarks, cycling and even a battlefield.

That battlefield was the famous Waterloo, in what is now Belgium, where Napoleon met his defeat in June 1815, and stepped down as emperor of France.

Now I’m not going to give you a lengthy history lesson—you can look that up if you’re really interested in more detail—but here’s a brief rundown.

In 1814 and after a military retreat from Moscow, Napoleon abdicated the throne in France and was exiled to the island of Elba. Less than a year later, he escaped from Elba and returned to Paris, where he regained supporters and reclaimed his title as emperor.

As a restored emperor, he re-gathered an army and set a goal of bringing Europe under French control.

The next few months are known as The Hundred Days or Napoleon’s Hundred Days. The period ended in July 1815 when King Louis XVIII was returned to power after Napoleon ‘met his Waterloo’ and relinquished his title.

So a bit about the battle

The battle involved almost 200,000 men, 35,000 horses, 500 cannons and seven European countries. Napoleon’s army faced two other armies—a multinational army led by the Duke of Wellington and a Prussian army led by Gebhrart Leberecht von Blücher.

Both Napoleon’s and Wellington’s armies were near Brussels when the fateful day began. Blücher and his army were much farther away.

It had rained heavily overnight and the battlefield was sodden. It’s possible that Napoleon’s decision to delay his attacks until the ground dried a bit may have cost him victory because it allowed Blücher to arrive at Waterloo.

You can check this website for more detail about how the battle progressed during the day, but I’ll jump to the end.

The attacks were vicious and bloody, but Wellington’s and Blücher’s armies managed to stop Napoleon’s march towards European domination. Wellington secured a peace deal with France and became Britain’s prime minister in 1828. Napoleon was exiled to St Helena, a small island off the coast of South Africa, where he died in 1821.

The site today

Waterloo’s terrain has changed. You can make out some of the ridges where battles were fought, but today’s main hill—Lion Mound—was created from soil nearby. This clip shows how the area might have looked in 1815.

Of course, we had to climb up the mound and walk as many of the pathways that were open for view. It’s sad to think how many lost their lives that day.

And a final footnote

Waterloo is also where Poor John captured his latest walking convert.

Food

And if you’re hungry, try out one of the recipes on my cooking blog.

I’ve never been a huge fan of modern art. It’s okay, but I don’t feel the need to rush out and see it. That all changed when I visited the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris.

Located in the Centre Georges Pompidou, it is Europe’s largest museum for modern art and it absolutely blew me away.

Room after room, piece after piece, I finally found a true love for modern art.

In reality, the love affair began when we were still waiting in the queue to go in. The building, which was commissioned by Georges Pompidou when he was president of France from 1969 to 1974, has its innards on the outers.

Yeah, you read right. The centre has been built inside out. The plumbing, escalators, ducting, pipes, air vents, stairs and all the other normal guts of a building are on the outside.

That seems to work because there’s plenty of amazing stuff reserved for the inside. In addition to all the modern artworks, the 7-storey structure houses a public information library and a centre for music and acoustic research.

Anyway, we had plenty of time to admire the exterior. We chose to go on the first Sunday of the month when admission is free. The queue was long, but there were plenty of buskers (including a woman playing the didgeridoo) and ice cream sellers to help pass the time.

But in the end, we didn’t wait all that long. The only hold-up was to make sure everyone passed through the airport-style metal detector, where I think my underwire bra set off the alarm. Oops, sorry, too much information.

And then we were let lose to travel up the escalators to the roof to see the great views of the Eiffel Tower (in one direction) and Sacred Heart (Sacré-Coeur) Basilica of Montmartre (in another).

Then it was back to levels 4 and 5 where the modern artworks awaited.

One of the most riveting pieces was a video and collection of stills by Jean-Paul Goude. Singer Grace Jones features in these, and I have to admit that I watched the video through twice. Absolutely spellbinding. So many images, so many themes, so much to look at.

But there are so many other noteworthy pieces. I loved an unknown-to-me piece by Picasso, especially because a mum lifted up both her sons to show the piece to them.

And then there were the wooden chairs at the round table, wrapped globes, hanging glass and…and…and!

Just go if you get to Paris. You can bet I’ll go again when I return.

A bit about the Centre Georges Pompidou

First an embarrassing confession! I’ve been to Paris four times since the Pompidou Centre opened in 1977, and this is the first time I’ve ever gone inside. So I’m giving myself a huge kick up the bum for being so remiss.

Three main architects—Renzo Piano and Gianfranco Franchini of Italy, and Richard Rogers of Britain—designed the centre. They won a competition that was, for the first time ever, open to international architects.

Early reaction to the structure was negative. National Geographic called it ‘love at second sight’ and an Italian newspaper said Paris had created ‘its own monster’.

Today’s opinions are much kinder and more positive. That’s my opinion, but plenty more agree. When it was built, the centre expected to have 8000 visitors a day. In its first two decades, it had 145 million visitors, more than five times the predicted number.

And attendance continues to be on the increase.

So go if you ever get to Paris. Please go! And you’ll be surprised to know that it doesn’t seem crowded.

Musée d’Orsay is one of my favourite museums in all of France.

A sense of awe swept over me even as I approached. The building itself, a converted railway station, is massive, stylish and stunning. The collection it holds is even more so.

The art, mostly French pieces dating between 1848 and 1915, includes sculptures, furniture, photography and, of course, paintings. Many of the paintings help to make up the world’s largest collection of impressionist and post-impressionist masterpieces.

We’re talking the greats of the world with works by Monet (86 paintings), Manet (34 paintings), Degas (43 paintings), Renoir (81 paintings), Cézanne (56 paintings), Gauguin (24 paintings), Van Gogh (24 paintings), Toulouse-Lautrec (18 paintings) and many more.

I was talking to my friend, Tony, about Musée d’Orsay a few days ago. He had a little grumble and said it had taken him 30 years to get over the creation of the museum.

Prior to the opening of Musée d’Orsay in 1986, many of the paintings were displayed in the Galerie National du Jeu de Paume, which Tony preferred. That building, which we didn’t have a chance to visit, is now a national gallery for contemporary art. In Napoleon’s day, it housed the courts for a special royal tennis game called jeu de paume.

But back to Musée d’Orsay.

The building

I’ll start with the building itself because it’s the first thing that overwhelms you. It started life as a railway station, Gare d’Orsay, which is obvious from the moment you enter. The station opened in time for the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, and served as the the terminus for the railways of south-western France until 1939.

By then, it was decided that its platforms were too short to accommodate the longer trains of the day. So it became a suburban station and centre for mail. It was also used as a movie set, temporary auction house and a haven for a theatre company.

It was supposed to be demolished in the 1970s, but the then minster for culture opposed plans for a hotel to be built in its site. Luckily for us, by 1978 it was listed as a Historic Monument.

At last it was decided to convert it to a gallery that would bridge the gap between the Louvre’s older art and the National Museum for Modern Art in the George Pompidou Centre (which I also love and will write about soon).

A team of three architects won the contract to design the new museum’s floor space and an Italian architect was chosen to design the internal arrangement, decoration, furniture and fittings. Once the building was ready, it took six months to install the thousands of works and the museum opened in December 1986.

In my opinion, the design is a brilliant success. There’s plenty of light and space, and I never got the crowded feeling that pervades the Louvre.

The artworks

Musée d’Orsay holds some of the biggest names in art masterpieces in the world. I’m not going to share a whole bunch of them (names or photos) here because you can go online and look up most of them. And what you find online will most likely have more information and a better resolution.

But here’s a short but stunning run-down.

Van Gogh’s Self Portrait and Starry Night over the Rhone

Gauguin’s Tahitian Women on the Beach

Cézanne’s The Card Players

Renoir’s Bal au moulin de la Galette, Montmartre

Monet’s Blue Water Lilies

Seurat’s The Circus

Whistler’s Whistler’s Mother

The furniture and sculptures are incredible too, but I have to confess that I didn’t recognise all the names, in fact, not many of the names. One I was surprised to see was Sarah Bernhardt. I had completely forgotten that, in addition to be a famed actress, she studied sculpting and produced some lovely works.

I was also pleased to see a bronze Pénélope by Émile-Antoine Bourdelle. I know her well because she also ‘lives’ in the Australian National Gallery’s sculpture garden in Canberra.

The photographs have missed out too. Oh, I saw them, but I didn’t photograph them. Photos under glass with museum lights all around mean reflection, reflection, reflection.

Interestingly, Libby told me on the telephone today that the museum’s current exhibitions include one on the prostitutes of France/Paris and another, which showcases photographs done by females.

A few last words

All I can say is that if you ever get to Paris, put the Musée d’Orsay at the top of your must-see list. And give yourself plenty of time—maybe a whole day (there’s a café so you won’t starve).

I’m not the only one who thinks the place is worth it. Libby, the daughter who lives in Paris and who has a degree in art history and curatorship, has bought an annual membership for only one museum—this one. And a brief check of TripAdvisor shows that it is the number 1 attraction in Paris. I have to agree.

It doesn’t take much time in France to realise that there is an entire etiquette and culture around the sacred baguette (or largish bread stick).

Every day someone in the family takes the short (sometimes extremely short) stroll to the local boulangerie (bakery) at least once a day and sometimes twice. Bread nuts might go three times a day.

Poor John did the daily bread runs during our stay, catering for the appetites and whims of four hungry and bread-starved adults. Every night there was a discussion about the coming day. How many ‘traditions’ (the name of the loaf we bought) do we need tomorrow? One, one-and-a-half or two?

No matter the choice, it was usually never enough and we had to have a second or third foray of the day.

Libby’s local boulangerie was less than 300 metres from her flat, but she and Daniel agreed that the bakery was going downhill. It used to be good, but the baguettes of late had been disappointing.

In fact, they were so disappointing that we decided to make Poor John walk an extra 200 metres to a boulangerie that was consistently good. And even though we didn’t need it, they sold gluten-free bread twice a week.

But using the new boulangerie was rather embarrassing. By now the closer baker knew us, and then he had to watch us walk by without purchasing. And then see us return with another loaf in hand.

What was he thinking? And where had we bought the other tradition?

But here’s when some more knowledge about France and bread comes in.

Most of France goes on holiday for the month of August. We arrived in Paris towards the end of August and can confirm that most of the city is closed and silent. Shop after shop had their shutters down, and the city seemed to be in hibernation.

But not all the boulangeries.

Up until two years ago, a boulangerie had to get permission from the government to go on holiday. It meant that no one would go without their beloved bread. Good grief, you can’t deprive your locals of a decent baguette.

Even now, when the law has been lifted, boulangeries coordinate their days on and off. Flayosc, a village we stayed in for eight days, has two boulangeries. They each closed one day per week, but on different days. And never on Sunday.

But back to Paris. Libby’s nearby boulangerie closes two days each week, but not the same days as the one farther on.

We also hear that, for the time being, she’s returned to the original boulangerie for most purchases—it’s lifted its game. Maybe the usual baker was on holiday.

And what happens after you buy

There’s an interesting etiquette about what you do after you buy a baguette.

I have to say that when you buy a baguette, it smells so darn wonderful and looks so tempting, that your first desire is to bite off the end.

Guess what? That’s another etiquette.

Most people chomp off a bit as soon as they walk out of the boulangerie. I didn’t know that at first and managed to take home complete loaves for a while. Once Libby told me of the chomp-off etiquette, I followed suit. And the evidence is here. Plus, I started noticing that almost everyone does the same.

Yum, yum, yum!

P.S. Poor John thinks there’s the makings of French film based on ‘when your boulanger goes bad’. Oh, and if you are a bread lover, my cooking blog has several great recipes including this one for yoghurt and herb bread.

Saint Tropez in the south of France may be the playground of the rich and famous, but it’s also home to a wonderful maritime museum.

Located in the dungeon of the town’s old citadel, the museum is only two years old, but it feels like it’s been there since ships first sailed into the town’s harbour. The views are great and the exhibits are beautifully done with explanations in both French and English.

As an aside, I’m always super impressed when museums in non-English-speaking countries go to the trouble of translating their display cards into English. You don’t see institutions in English-speaking countries translating their display cards into any other languages very often.

But back to the museum—or shall I say into the museum? We crossed a drawbridge to go in, and got one of those rare benefits in France—a senior’s discount. Libby and Daniel had to pay full price, but then we paid for them, so our reduction didn’t matter much.

The museum is well laid out, with simple but effective displays that showcase the everyday lives of those who went to sea, and the men and women who lived and worked around the harbour.

Near the end of the tour, there’s a remarkable film showing a ship sailing through calm waters and then surging through a terrible and frightening storm. The display is especially clever. There’s a place for four to six people to lie back and watch the film being projected onto the ceiling. My photo is a bit out of focus, but I’m using it anyway because I really wanted to share the cleverness of the presentation. I think one of our party dozed off during the film, but i was spellbound.

Looking back over my photos, I’m surprised that I took so few in the museum—must have been mesmerized.

And if you’re new to the blog, you should check out the great meal we had in St Tropez or another great ‘seafood-y meal’ from my cooking blog.

After the warm and fuzzy post about Samuel and Poor John and their clasped hands, I have grumpy news to report.

Yesterday, for the first time ever, I encountered an extremely rude member of Australia’s ‘official’ airport welcoming committee (immigration). She was behaving rudely to incoming travellers. I was horrified and embarrassed.

An elderly Chinese couple were on the receiving end of her grumpiness. They may have had Australian passports, but it was obvious that English was not their first language and paperwork was not their strong point.

When I was next in line to go through border control, the couple was off to the side, and had just finished filling out their entry cards. I let them in ahead of me.

Nope, said the border officer gruffly, these aren’t complete. You haven’t done the back, she said tapping the card angrily. It was easy to see that they were confused and distressed, but she waved them away to get on with the job.

I was next and was soon to learn that I had committed my own special crime. I can’t accept this. It’s done in purple ink. You have to do it in blue or black. My explanation that my blue pen had run out of ink on the plane, which was true, was rejected.

Do it again, she ordered, and as I picked up a pen from the counter and unconsciously put it in my mouth, she added with a finger wag, and get that pen out of your mouth. Who knows how many people have handled it!

So I spit out the pen and moved to the ‘Group W bench’ with the Chinese couple—if you don’t understand that reference, listen to Arlo Guthrie’s song Alice’s Restaurant.

I started to re-do an entry card. Mind you, crabby Border Force woman—she was no lady—did not offer me a blank card, but I had miraculously taken two when they were passed out on the plane.

But as I scrawled my black-ink version—hey, if I was going to get done for a violation it should have been for poor penmanship—the Chinese couple stepped forward to present their cards once again.

Nope, nope, still not right, still not complete, she said tapping the card again and not explaining what still needed to be done. The man was so flustered and then came the official’s last snide comment, almost under her breath, but I heard it and understood it.

Surely you can fill out the form right. The last Chinese guy could do it right, and he was a ‘real’ Chinese. Didn’t even have an Australian passport.

I could have slapped her silly, but then I’d be reporting from jail, perhaps even solitary confinement.

But the saga continues. We had dinner with a large group of friends tonight and I heard a similar story from someone who had recently received a similar ‘welcome’ from our front-line at the airport. Same nasty spiel, but a different person.

I can’t help but think the surly and unwelcoming manner stems from Tony Abbott—our mean-hearted and recently ‘deposed’ prime minister.

He renamed our immigration officers as the Australian Border Force and put them into military-style uniforms. And all at a cost of $10 million.

I hope this gruff attitude is short-lived. It’s a sad change from the welcomes I’ve received in Australian airports in the past.

Louise, one of our exchange students from France, summed it up well. She remembers that her arrival in Australia a few years back was one of the nicest she’d ever experienced.

She had something to compare to. When she arrived in the USA when she was 14, she was interrogated as to why she was travelling there on her own. She was on her way to visit relatives.

A year later and at age 15, she was coming on her own to Canberra for a year and she rather expected similar treatment. But she remembers fondly that the immigration officer opened her passport, checked her visa, added a stamp and with a big smile said, Louise, welcome to Australia.

Seriously, it’s not that hard to be nice.

P.S. I’m embarrassed to admit that I did not stop to help the elderly couple complete their cards. I should have and would have if we had not already been running late.

P.P.S. Oh, and a comment about those damn entry cards and Poor John’s experience. He had gone ahead of me. We both have ‘smart’ passports. His in-built smart chip still works and mine doesn’t, so he was cleared by a machine and not a person. No one ever looked at the offending purple ink on his entry card.

So I wonder whether anyone will ever look at my black-ink version besides the crab-puss at the immigration counter (she only glanced at it to make sure it was done in black or blue). I still have the purple version and share it here as evidence.

Regular visitors to this blog will know that Poor John has a tendency to walk with his hands clasped behind his back.

After years of watching him do this, I have concluded that the condition is both genetic and catching.

There is plenty of photographic evidence already on this blog. His daughters do it, his siblings do it, friends do it, sometimes I even do it. People even send me pics of other, unknown, people doing it.

But we had an especially amusing episode the other day at Waterloo in Belgium.

We were there with Jean-Mi (our very first exchange student), his partner, Sali, and their two-year-old son, Samuel. Ah, two years old, you say. Yes, two-year-olds have some very definite ideas about how the world is supposed to operate around them.

On this day, hands behind the back were a big no-no.

Samuel trotted along behind Poor John—determined to stop him from having his hands behind his back. Stop, stop, he ordered in French, as his small hands tried to prise apart Poor John’s interlocked thumbs. We all smiled, but were careful not to encourage him by laughing out loud.

Yet he persisted until suddenly it dawned on him that this might be worth trying. Maybe Poor John had the right idea. Hmm! I guess I’ll give it a try, he decided.

So he clasped his hands behind his back, and that’s the way things went for the rest of the afternoon.

The pics are here to remind him of that day. I wonder if it will be one of those childhood memories that, in years to come, he’ll vaguely recall some guy who ‘taught’ him to walk with his hands behind his back.

And speaking of kids and their memories, my great nephew Georgie remembers helping me make scones just before Christmas. Thanks Georgie.

The Gates of Hell, commissioned in 1880 for a decorative arts museum that was never built. Note The Thinker near the top, and The Three Shades at the very top

A life-size version of The Three Shades. They point to the inscription that reads ‘Abandon hope all ye who enter here’

Artworks by French sculptor Auguste Rodin hold a special interest for most Canberrans, probably because our National Gallery of Australia has a set of his famous The Burghers of Calais.

We’re frequent visitors to the gallery’s sculpture garden and never fail to admire these colossal statues that represent a group of 14th century citizens of the northern French town of Calais. The six men had offered themselves as hostages to induce the English to lift a siege during the Hundred Years War, and spare their starving city.

Years later, when Calais was planning to tear down its medieval walls, the town decided to erect a monument reflecting its ancient history. Rodin pursued the commission eagerly and won it in 1884.

I’m not sure how many sets of his bronze burghers have been cast (possibly 12), but we were delighted today to see a complete set—along with many prototypes—in the Rodin Museum (Musée Rodin) in Paris.

Hôtel Biron and surrounding gardens. This main museum of Rodin’s work is currently being renovated and is not open to the public

Well, we weren’t actually in the museum proper—the Hôtel Biron—which Rodin used as his workshop from the early 1900s until his death in 1917. At present, the main museum is closed for renovations, but the garden is open, as is another building with a temporary exhibition of about 140 pieces of Rodin’s plaster casts and other studies.

The top drawcards for most visitors are the burghers ensemble, The Gates of Hell and The Thinker. But many other items are displayed with accompanying explanations—in French and English—so Poor John and I were able to read all the details.

I hadn’t known that a small version of The Thinker was originally created as part of The Gates of Hell, which depicts ‘The Inferno’, the first section of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

The massive gate sculpture is 6 metres high, 4 metres wide and 1 metre deep, and has 180 figures. Some are as small as 15 centimetres high (6 inches) and others range up to one metre.

The Directorate of Fine Arts commissioned the work in 1880 and expected it to be delivered by 1885, and used as the showy entrance for the planned Decorative Arts Museum.

The museum was never built, but Rodin kept working on the gates until his death. He enlarged many of the individual parts, including The Thinker, to life-size sculptures in their own right.

As we went through the exhibition we got a distinct impression that a lot of Rodin’s work was never completed, completed late or a source of criticism. In fact, Poor John wondered if Rodin ever got paid for his work, but Libby and I thought that he must have had a patron or received advances or both.

Nevertheless, the scandals and furore are interesting.

Rodin spent years working on a monument to Victor Hugo, the famous French author who wrote, among other things, Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

The saga began in 1883 when Hugo refused to pose for Rodin. Instead the artist spent hours one day on the author’s veranda, making 60 sketches of the author, who paced the garden at a distance.

After Hugo died in 1885, the French government commissioned Rodin to design a monument to him.

Rather than a routine approach, Rodin depicted the author in exile, seated among the rocks of Guernsey. This first effort was deemed to lack ‘clarity’ and the ‘silhouette was muddled’. It was unanimously rejected by those commissioning it.

Rodin tinkered with this and other versions on Hugo (including a nude) over the next decade before abandoning the project completely. The seated version was first cast in bronze in 1964.

The plaster sculpture of French author, Honoré de Balzac, drew criticism from the moment it was first unveiled to the commissioning organisation, the Societé des Gen de Lettres in Paris in 1898.

By then, Rodin had worked on the sculpture since 1891, rather longer than the 18 months allowed for in the original agreement. That was because Rodin had become obsessed by the author’s works and history.

After reading all of Balzac’s works and carrying out almost 50 studies on the man who died in 1850, Rodin decided to create a sculpture that captured the author’s ‘persona’ rather than his image.

While the critics were not impressed and the societé rejected the sculpture, Rodin’s contemporaries, such as Cézanne, Monet and Toulous-Lautrec, liked it.

The sculpture was not cast in bronze until 22 years after Rodin died. Today many castings are displayed around the world and the work is often considered the first truly modern sculpture.

Near the end of his life, Rodin donated sculptures, drawings and reproduction rights to the French government.

I have a story to tell about Rodin’s mistress, Camille Claudel, which I’ll tell when I do a post about the two guided walks we did in Paris.

In the meantime, enjoy a drink on me—limoncello cocktail.