We had a wonderful three weeks in Iran—visiting Tehran, Isfahan, Qom, Shiraz, Yazd, Persepolis, Kerman, Mashhad and even a small oasis.

Everywhere we went, people went out of their way to be friendly and helpful. Fellow passengers were gobsmacked when, during lunch stops in small towns, complete strangers would offer us lifts (rides) to food markets or small restaurants.

Western media is pretty hard on Iran and most Iranians worry that a lot of the outside world views their country with suspicion and mistrust. We were constantly asked how we liked Iran, whether the cities and sights were enjoyable, and if people were being helpful and kind to us. The locals showed visible relief when they heard that we held them and their country in high regard.

High regard puts it mildly. In reality, we were all overwhelmed by the kindness and generosity shown to us throughout the country. And the touristic sites are pretty sensational too.

But there was one big exception and, unfortunately, he played a big role in our day-to-day lives in Iran.

Rafi was supposed to be our local guide, instead he was our local headache.

Sometimes it’s mandatory for a group to have a guide when they travel through Iran. For various reasons, we were such a group. Our driver, Suse, managed to cover the distance from the border to Tehran without a guide, but things changed by the capital.

While Suse had hoped to tour Iran without a guide, she had had some early email contact with Rafi as a possible guide. But her first choice was a woman she met on her first night in Tehran. Unfortunately that woman was already busy with another group.

A third prospect appeared the next morning saying he was our official guide, bragging that he had all the details for our group of nine.

Enough bragging, buddy, said Suse. You must have bought sketchy details from a guard at the border crossing because our group is 14.

So the job fell to Rafi by default. He seemed okay at first, but from the first bush camp it was apparent that he wasn’t the person for us.

In countries where a guide is compulsory, that person’s role is to shepherd you from place to place. They are supposed to keep you on the appointed path and make sure you don’t get up to any ‘mischief’. They aren’t supposed to run the show. On an overland trip, the driver (or the tour leader , if there is one) makes the decisions and keeps the itinerary on track.

For our truck, breakfast happens an hour before departure. Tents should be down and packed away before the meal starts, then we eat, wash up, pack up the ‘kitchen’ and our own day-to-day gear, and brush our teeth. We can accomplish all this in just about an hour.

Suse explained this daily morning routine to Rafi—more than once—but on that very first morning, he begged for a couple of minutes to explain some history of Iran and where we were headed next. Thirty minutes later, we’re desperate to finish our daily duties and get on the road.

Now don’t get me wrong. I would have thoroughly enjoyed a 30-minute spiel that was interesting, informative and useful. But Rafi gave us a rundown of all the dynasties in Iran from the beginning of time—with no dates, embellishments or anecdotes, and virtually no mention of where we were headed next. Good grief, we hadn’t signed up for a history class. And if we had, at least it could have been made interesting, engaging and relevant to our travels.

Frankly, Poor John—with his wonderful story-telling voice and his amazing memory for the details of everything he reads, especially the quirky—makes for an infinitely more entertaining and enriching guide than Rafi could ever hope to be.

So we were lumbered with a guide whose greatest skills were superb English and knowing where things were in a town, but very little information about the cities or monuments themselves.

Worse still, he told fibs, or they seemed like fibs. For example, the day before we arrived in Kerman, he told us there would a bank holiday the next day, but that we shouldn’t worry because everything would be open. The next morning, he told just one passenger, quietly and on the side, that it’s a pity everything will be closed here today because of the religious holiday. Rafi is supposedly quite religious and you think he’d have known about a national religious holiday. Of course, he knew, he was just being devilish and this was not the only occurrence.

The final frustration came a day or so out of Mashaad. The temperatures were blisteringly hot, and Suse and Rafi consulted over stopping at a particular oasis so we could spend the heat of the day in the shade and resume our travels later in the afternoon.

In late morning as we paused at the likely oasis, Suse asked if this was the right place. No, no, said Rafi, another 40 kilometres. So we drove on for another six hours without seeing a single oasis.

In the late afternoon when we were still moving, Rafi told me privately that he had organised with his friend in another oasis—much farther on—for us to stop and have food and tea.

Have you told Suse? I asked. No, he replied, but it will be a very nice stop.

Yes, the oasis, when we finally stopped, was lovely and we spent about 30 minutes there. But after a scorching day on the road and one that ignored a specific request to avoid the heat of the day, Suse was furious. She let Rafi know—in a stern but even-tempered voice—that she was not at all happy and that he must not continue to try to override her decisions and requests.

In the end, Rafi decided to stay behind in the oasis. Suse did not ask him to leave, but he came on the back of the truck, announcing that he was leaving because he wanted to be part of the solution and not part of the problem.

That’s when things went really sour because he knocked himself out trying to be our major problem over the next couple of days.

It appears that he hopped in a taxi at the oasis and preceded us to Mashaad. At each police checkpoint, he must have urged them to interrogate us and make life as difficult as possible.

This was a major change because we had had no police issues up to that time, and usually Rafi never even showed his face at a checkpoint, so they had no way of knowing whether or not we had a guide on board.

He also began to send Suse a barrage of emails threatening to have us deported, saying she was in cahoots with the devil, and a range of other ridiculous claims and accusations.

Before our last night in Mashaad, he fabricated a story that as overland passengers, we could not remain at the homestay we were using—that we must move to a hotel. Funnily enough, the ‘recommended’ hotel was hugely expensive and one, we later learned, from which he got a commission.

Unwittingly, Suse booked us into a different hotel and the manager of that place told her that Rafi (who considers Mashaad his hometown) was a nasty character and not to be trusted. Hmm! Useful news, but given way too late.

Since we left Iran, he has continued to be a menace from afar. Sending threatening emails, promising to report the overland company and the homestay place we used to the authorities, in an attempt to have everyone banned. All very annoying and disappointing behaviour.

Admittedly, Poor John and I, and Diego (our Italian travelling companion), did go around most of the cities we visited with Rafi. He was quite useful as a map and translator, but as Poor John said, the problem is he doesn’t know anything else about the places we visit.

But you know what gave it all away for me? Early on in the trip, he said he wanted to buy a gift for his wife and could I help him choose something. How sweet, I thought.

When’s her birthday? I asked.

I don’t know, he replied.

Well, at least what month?

I don’t know.

Now there’s a man not to be trusted.

Have you ever had a crappy guide on your travels? Oh, do tell!

P.S. Luckily, I have many more good stories to tell about our time in Iran. Stay tuned. And be sure to check out my cooking blog.

I’ve always planned that when I fall off my perch, I‘ll be bundled into a cardboard box and burnt to a crisp, but then I saw Tomb of Astan-e-Shah Nematallah-e-Vali in the desert near Kerman in Iran!

There’s a park in front of our house in Canberra. The neighbours (and us too) have always worried that this lovely space might be sacrificed for a complex of apartments, but I’m sure a sacrificial new tomb would make a great touristic site. And give the neighbours something wonderful to look at.

As with so many of the sights we visit, I had never heard of Shah Nematallah or his tomb. Born in 1330 in Aleppo Syria, Nematallah (there are a whole bunch of slightly different spellings of his name) was a Sufi master and poet.

In his younger years, he travelled throughout the Muslim world, studying under different philosophers and searching for a spiritual leader. He ultimately became a disciple of Abdollah Yafe’I in Mecca.

He went on to settle in Samarkand and finally in Kerman, in southeast Iran. He is considered to have established the Nematallahi order of Sufism. This order has now declared itself Shia Muslim.

By the time Nematallah died in 1431, his fame had spread across Persia and India. His tomb, in fact, is under the authority of Achaeological Survey of India.

I reckon few tourists make it to Nematallah’s fabulous tomb and surrounding gardens. That’s a pity. We made a special side trip to visit, and I’m so glad we did. The complex was built in the 15th century and is about 35000 square metres in area.

Now we just have to convince our kids to squander any inheritance they might receive on a Canberra version of such a tomb. The park out the front of the house would be just the right size!

Everywhere we travel, I like to take pics of people going about their daily jobs.

Iran is still a country where lots of work is done manually, without the benefit of aids to lift or shift heavy loads.

Oh wait, there are such aids—they’re called muscle power. And the work involves a lot of pushing, pulling, stretching, bending, digging, sweeping, loading and twisting.

The pics here come from all over the country and give glimpses of markets, streets, alleys, shops and touristic sites. These are all city shots and I’ll do a separate blog on the countryside at work.

I really wish I could have included a few snaps of the women who looked after us in the hammam (bathhouse) in a village near Mashaad. A bathhouse is not the place to take a camera, unless it’s an underwater version. Water is flung everywhere. And you wouldn’t call the staff modest.

The two gals who tended to the four of us were weathered old birds. Perhaps as old as me! J And they were wearing only shower caps, saggy underpants and slip-on rubber sandals—just the gear for exfoliating and scrubbing down four tourists who were wearing even less.

This was my first-ever trip to a hammam as a customer—I’ve been into plenty old decorated ones as a sightseer.

My fellow travellers were most apologetic that it wasn’t more deluxe for my first scrub-down experience. But I didn’t mind visiting this simple village bathhouse with none of the fancy décor, tiled pools and perfumed luxuries of the tourist traps.

Because we were in the local bathhouse, there were already several women bathing when we arrived. Over time, a couple of families arrived—even one with three generations of grandma, daughter and granddaughter. One toddler screamed in terror when she saw these four strange foreign faces that dazzled back at her, our skin almost as white and clinical as the tiles on the wall and floor. Mum was super embarrassed, but we thought it was funny. The tears and wails subsided soon enough, so I doubt the child is permanently scarred.

We were scrubbed and sloshed down from huge rubber buckets and I think my hair was washed with what might have been carbolic soap. It certainly displayed a fantastic stiffness for several days after the experience—until we reached our next showers.

The display of flesh, jiggling of boobs and vast expanses of cellulite were most unexpected in this hugely conservatively and normally covered-up country.

We did, however, miss out on the dilapidation. Our hostel host, Vali, organised this outing for us through his wife. His parting words as he dropped as at the door were to ‘be sure to have the dilapidation’.

This service was never even offered to us! But it was to the fellows who visited the gents’ side of the hammam. Diego and Quinn opted for some hair removal. Quinn, ever the goofball, chose to have a smiley face of hair removed from his chest. Sorry ladies, but no pics.

And Poor John—yes, Poor John willingly signed up for a stint in the hammam (and I nearly fainted when he said he’d go). He declined the hair removal option—just like he skipped getting a tattoo in Thailand. He hasn’t said much about the hammam experience, and I’m wondering if he’ll ever do it again. I’ll keep you posted.

Have you ever been to a hammam? How was it?

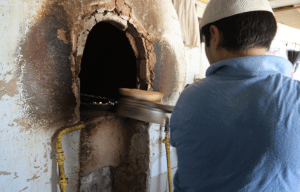

There’s nothing better than fresh bread, but when you get something like this—it’s better than better.

Poor John was talking about a small loaf of bread given to us by a woman who was baking hundreds of loaves every hour in a small bakery on the back streets of Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan.

We’ve had lots of fabulous bread as we’ve travelled through Central Asia, but this loaf was somehow more fabulous than all the others.

It was pure luck that we found it. We were walking along the streets of old Tashkent behind the Friday mosque—the area isn’t really that old because much of the city was flatten in an earthquake in 1966.

As we passed a boy selling bread, I said, that bread smells incredible. But we walked on. Cripes, we’d finished breakfast only an hour earlier.

Then Poor John spied the doorway of what he thought was a small restaurant. Oops, still too early for more food. But as we passed by the window of the ‘restaurant’, I caught a glimpse of the bread oven and a whiff of the baking bread.

Time to double-back. I ventured into the ‘restaurant’. Hello, I said. A plump woman kneading bread flashed a broad smile and replied good-bye in English, and then caught herself. No, no, I mean hello. Come in. Please come in.

This was bread heaven—four 50-kilo bags of flour, scores of dough balls already waiting to be oiled, kneaded and punched into loaves AND that bread oven! It was about the size of a largish walk-in closet and powered by gas, and the woman’s assistant was loading it with up to 100 loaves of bread at a time.

We watched a demonstration of the whole process and I even got to punch a couple of loaves with the nail-studded tool used to imprint the middle of each loaf. Psst! I bought a couple of those tools in Khiva and can’t wait to try them out at home.

We stood, watched and listened for probably 15 minutes—seeing dough slapped against the oven wall and then, later, being lifted off and stacked on a wooden tray for the young boy (remember the one I saw earlier) to collect loaves for his next sales expedition.

As we said our thank yous and good-byes, the woman slapped her forehead with the heel of her hand and slipped into Russian or Uzbek. I can’t confirm what she said, but it must have been along the lines of—Good grief! Where are my manners? After all this, you must have a loaf to eat. Here, take this one. And she popped it into a small plastic bag and thanked US profusely for OUR visit.

We, in turn, thanked her profusely for such an amazing experience.

Poor John and I continued on our walk and took about 10 minutes to polish off the entire loaf. I will remember the taste forever, and will try to duplicate at home. Just in case, I bought a book of Uzbek cuisine with a large collection of bread recipes. If I crack a good recipe, I’ll share it here.

And if you love bread, please try out my page-32 recipe for Middle Eastern bread. It’s darn good, but nowhere near as good as the bread we ate today.

If we’d been in a movie, the flames would have shot 20 metres in the air and the bus would have exploded just when we got close enough to be saved by a local hero or blown into tiny pieces that had to be scraped off the nearby newsstand.

But it wasn’t a movie, so the crowd surged forward to watch the burning bus and the fire department turned up in time to bring everything under control.

The newspaper reporter in me is so glad we didn’t miss this. We were descending the stairs from the Kukeldash Medressa (more about that soon), when both Poor John and I noticed smoke billowing from the back of a local bus.

My instinct for getting a decent picture for the front-page kicked in and I rushed forward to get a closer look. Poor John hesitated and pointed out the knuckleheads who were throwing buckets of water on a gas-fueled fire.

Hmm, not smart, so I stepped backwards for a moment, then realised this wasn’t a movie and the chances of the bus exploding were slim, or at least a couple of minutes away.

So I snapped away until a random fellow on the street crossed his arms to signal that photos were forbidden. ‘Oh, pleeze, Mr Do-gooder, what could be wrong with a few pics of a bus fire’. But I was pretty sure I had a couple of decent pics so put the camera to the side and watched the fire crew hack their way through the seats at the back of the bus and then spray foam all over the disaster.

I was pleased to see that the captain (er, bus driver) stayed with his ‘ship’ until he was forcibly told to go. All the passengers were gone (left not deceased), by the time we noticed the commotion.

When we finally walked away, there was still a bit of fire under the bus, but we hung around the bazaar long enough to know that it never blew up. Not sure that it will ever run again either.

Tehran’s main bazaar might not be one of the most beautiful markets in the world, but you can buy almost everything you need.

It’a one of the world’s largest bazaars with about 10 kilometres of covered shopping and plenty of outdoor stalls too.

Poor John and I spent half a day wandering the labyrinth of corridors getting ourselves lost and then found—and finding lots of unexpected gems as we explored.

For starters, we replenished our supplies of dried fruit and nuts, and I found a headscarf that didn’t make me look too frumpy. It’s black, red and gold and has sort of an Aboriginal design. I might even wear it in public in Australia.

It’s compulsory throughout Iran for women to wear a headscarf—or even the full shapeless chador rig with or without face covering, which is way too hot in summer and not expected of foreign women. I brought two scarves with me from Australia, but neither quite covered my head, hair AND neck, so a better version was required.

I was also tempted by, but resisted buying, some fabric or a large men’s shirt (to cover my bum). In addition to a headscarf, a woman who doesn’t wear a chador seems to be expected to wear a jacket that is long enough to cover her bum. Good grief, I’d brought black trousers and black, long-sleeved (but not very long) tops, and figured I’d wait until someone complained about my outfits before I bought yet another layer of heat in summer. No one ever said a word.

We also ignored the touristic trinkets. There are plenty of wonderful temptations, but after years of travel, we already have too much of this stuff at home.

The evening gowns were most impressive and most unexpected, but I resisted buying one of them too—not really right for camping. I’m still wondering who buys these shapely, slinky, low-cut numbers festooned with beads, sequins, ruffles and glitter. I saw plenty of women in chador lingering before the displays of gowns, and I asked in several shops as to when and where people might wear such get-ups. But the language barrier was too great to get an explanation. I can only imagine that headscarves, long jackets and chadors are not required in the privacy of one’s home, and that a dinner party among ‘consenting adults’ would be the perfect place for a plunging neckline.

So skipping the party clothes, I was especially pleased to be able to resurrect my watch. You may remember that my trusty watch of ten years fell off my wrist—and was lost forever—in Sydney’s airport late last year. Luckily, I had a convenient spare in my backpack. It’s a Timex and, while it’s been mostly okay, it’s also been a nuisance.

I love the watch’s beautiful big face, large readable numbers and sweeping second hand. Plus when I push the winder spindle in the middle of the night, the face lights up and I know how many hours I have until I have to crawl out of my sleeping bag.

All these good points reminded me that when I was a child, Timex’s promotional slogan was ‘takes a licking and keeps on ticking!’ I vividly remember the watch being tied to the blade of an ice skate and being whizzed around the skating rink, and then shown to still be keeping good time.

Clearly, I didn’t get that watch! Within a few months of normal wear, the face edges had chipped. I can live with a few chips, but not when the shards lodge under the face and stop the ticking. I could shake the watch to re-distribute the shards and get the hands going again, but I was always wary as to whether the time shown was accurate.

Then one of the pins holding the watchband in place fell out. Hmm, and I hadn’t even gone to the ice skating rink in Dubai! But Dubai is the land of copies, so I packed away the Timex and purchased a cheap Rolex copycat that was way too dressy for my wardrobe of camping clothes. Maybe I should have looked more closely at the evening gowns in Tehran.

That said, the Tehran bazaar came to the watch rescue. Early in our wanderings, Poor John found a proper clock shop. They couldn’t replace the face, but they were happy to provide a pin for the band—for free!

Later in the day, we found a proper watch shop and—yes—for a mere $5 they could replace the face by the next day. Our challenge was going to be to find the shop again, which we did—eventually.

So I’ve got a watch again that doesn’t need sequins to go with it. Sadly, the frequent and extreme changes in temperature (from boiling hot in the desert to the air conditioning that’s available occasionally in hostels) have caused the watch face to crack, so I’ll need to go replacement shopping again in one of the Stans. I’ll keep you posted.

Poor John and I really appreciate everyone’s good wishes for our safe travels.

I suspect you all worry that we’ll be robbed at gunpoint, taken hostage in some remote location, tossed into prison on some trumped-up charge, or mistaken for terrorists or criminals, as I was when I crossed in to Turkmenistan in 2011.

Your concerns are misdirected. In all seriousness, the most likely disaster waiting-to-happen starts with our attempt to cross the road.

Oh sure, all these countries have zebra crossings—those white stripes painted on the road to indicate is where you should cross. But in this part of the world, a zebra crossing is really a rough indication of where you could take your life in your hands should there be a slight pause in traffic.

Every now and then motorist surprise us. Yesterday as we hovered at kerbside in Bukhara, one of Uzbekistan’s top tourist destinations, a car actually stopped at the zebra crossing. Shamed by this act of selflessness, fellow motorists across three lanes of traffic actually stopped at the crossing, allowing us to briskly walk across the road, rather than duck and weave through the maze of vehicles.

But generally we wait for a gap in the flow of traffic. Then we proceed slowly with a hand extended towards oncoming vehicles. We figure that motorists don’t really want to hit us, but they don’t want to stop either. We try to make it easy for them to see our intentions, so they can slow down a bit and swerve around us.

So hone your skills on assessing speed and distance, and learn to proceed slowly with your eyes locked on the traffic.

And if all else fails, you can do what we had to do once in Indonesia—hire a rickshaw to take us across an eight-lane road.

P.S. By the way, the crossing shown in these photos (in Iran) was NOT done against a red light. The green pedestrian light was on for all three pics.

Tehran is overrun with palaces, but the showpiece has to be the Golestan complex of palaces, museums and halls near the centre of town.

Surrounded by an ancient wall, this combination of buildings, mirrors, stained glass, tiles, mosaics, marbles, woodcarvings, enamels, gardens, fountains and more is the city’s oldest monument.

Poor John and I spent almost half a day exploring Golestan’s lush gardens and lavish buildings.

They have a cunning, money-making admission system. We paid 150,000 rials (better known as 15 tomans) or about $5 to get in. Then we paid an extra 50,000 rials per individual building we wanted to visit. There’s a big map to choose from, but the lack of explanation makes it hard to pick. Luckily, we only had to specify a number of buildings and not give exact names.

In the end, a local guide standing near the ticket counter suggested which buildings to skip, so we bought tickets to visit five of the nine on offer.

Golestan Palace is one of the buildings that made up the city’s historic citadel (Arg), which was built in the 1500s. In the late 1770s, the palace became the official residence and seat of government for the royal Qājār family. In 1865, Haji Abol-hasan Mimar Navai had it rebuilt in its present form.

The palace’s most characteristics features and rich ornamentation date from the 19th century. They incorporate traditional Persian arts and crafts as well as elements of 18th century European motifs and styles.

In addition to being used as the governing base of the Qājāri kings, the palace also functioned as a recreational and residential compound and a centre of artistic production during the 19th century.

During the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty (1925–79), the palace was used for coronations and formal royal receptions. The family built their own formal residence at Niavaran. In fact, Reza Khan (Pahlavi senior who reigned from 1925–41) had much of Golestan demolished because he thought the old structures might stand in the way of modernisation.

Marble Throne

Such a pity he felt that way. After all, his coronation was in the famed Takht-e-Marmar, or Marble Throne.

Built more than 200 years ago, the Takht-e-Marmar and its surrounding terrace are adorned by paintings, marble carvings, tile work, stucco, woodcarvings, enamels and lattices.

The actual throne sits in the middle of the terrace and is made from yellow marble from the Yazd province. It was designed and created by the Qājār court’s main painter and several master artists. It is said to include 65 pieces of marble.

Shamsolemārah, Building of Sun

The Shamsolemārah, or the Building of Sun, is considered the complex’s most significant and beautiful structure. The ruler Nassereddinshāh had seen pictures of multi-storey buildings in Europe and decided he had to have his own. The Shamsolemārah’s two tall towers made it Central Asia’s first ‘skyscraper’.

Karimkhān’s Sanctum

Then there’s the Karimkhān’s Sanctum, a verandah with three arches and a small marble throne. This was supposedly a favourite spot for Nassereddinshāh, and where he spent private time smoking his hookah. His tombstone is here.

Chādorkhāneh, tent warehouse

Given that we are camping most of the way from Tehran to Beijing, I was rather taken by the Chādorkhāneh, or warehouse for royal tents during the Qājār period. Apparently, Qājār clan members loved the great outdoors and living in tents. I bet they loved having their servants trot along to put up the tents and cook and serve meals.

Emarat-e Bagdir, Wind Breaker

But the Wind Breaker (wind catcher) Building is certainly one of my favourites. Also known as Emarat-e Bagdir, this was the second structure in the Golestan Palace complex.

The four wind catchers that rise overhead capture the breeze, making the building cool during the hottest months of the year. But I like it because it’s just so darn beautiful. I could have wandered in the darkened rooms for the rest of the day.

Mirror Hall

A final stop was in the Mirror Hall. Photos aren’t allowed, but an iPhone on silent works wonders. I reckon the guard knew what I was up to, so I limited my bad behaviour to a couple of snaps.

P.S. Many thanks to the webmaven for telling people our news until we could get online again.

Just a quick update from the webmaven. I should also start by apologising for the slackness of this message as neither of us could remember the password to the blog.

Peggy has been travelling through Iran and recent reports have her alive and well in Turkmenistan – famous for the obscure laws of its “President for life” (he’s dead now), including one banning beards! But that’s pogonophobia for you! Thankfully Poor John shaved his beard off in the late 80’s, an act for which I never forgave him.

She has asked me to post to let you know she hopes to be online soon to regale you with her many tales.

In the meantime you can read up on Turkmenistan’s eccentric previous dictator on his wikipedia page: Saparmurat Niyazov

The Art Gallery of New South Wales was the second (and only other) Biennale of Sydney venue we got to last week. I’ve already written about Cockatoo Island.

I hadn’t been to this gallery for ages and ages, and it was great to see the contemporary biennale exhibits as well as the special Afghanistan: hidden treasures from the National Museum, Kabul, which is on show until 15 June 2014.

The Afghan works are breathtaking and I’ll cover them separately, so today’s post is limited to the biennale and a selection of other works permanently held by (or on loan to) the gallery.

Biennale works

We first came upon a series of 19 photographs of people in their birthday suits—but elaborately embellished. Created by Deborah Kelly with support for probably 100 collaborators, this work is entitled No human being is illegal (in all our glory).

Each work measures 2.1 x 1.12 metres. They are displayed in a long, narrow corridor so it was impossible to photograph the collection in its entirety.

One of my favourites was We all need forgiveness by Bindi Cole of the Wadawurrung people. Each panel of this video and sound projection was revealed over time, with each person saying the words I forgive you. The cycle lasted several minutes, and the exhibit was popular with many.

My other favourite was Majority rule by Bidjara artist Michael Cook. This series of seven black-and-white photographs uses the same Australian Indigenous male protagonist over and over again. The photos reminded me of the sometimes used, and often denigrating, expression of ‘but they all look the same’.

There was a little bonus/task at the end of the biennale exhibits. The task—we were asked to complete a survey. The bonus—we’re in the draw to win two tickets to anywhere in Europe compliments of Etihad Airways. We can dream!

Other works

Margaret Olley is one of Australia’s best loved artists. A prolific still life painter, she died in 2011 at the age of 88. Remarkably, she was the subject of two Archibald Prize winning paintings; the first by William Dobell in 1948 and the second by Ben Quilty in 2011. Both were on display side-by-side, with Quilty loaning his to the gallery. They are so entirely different.

I have a special reason for loving Olley and her work—she was the queen of mess. The Sydney Morning Herald even used her as an example in an article of mess versus tidy. Her Paddington home was described as a ‘masterpiece of mess’ and the clutter was typical of her eye for still life.

As a permanent tribute to her talents as well as her mess, part of Olley’s home studio has been painstakingly dissected and reassembled at the Tweed River Art Gallery in Murwillumbah.

There are also some fantastic Aboriginal bark paintings and graveposts. The thunder spirits was painted by Munggurrawuy Yunupingu from the Northern Territory in 1961. The graveposts were completed in 1958 by six Tiwi artists from Melville Island.

And finally is Brett Whiteley’s The balcony 2 of Sydney Harbour and the Sydney Harbour Bridge. I should have added the other day to my blog post on the harbour and bridge. While I haven’t seen the harbour from that balcony, I have stood on the edge of the front yard of that house in Lavender Bay and gazed down on the water. I promise to go back and take you there.

In the meantime, check out my cooking on page 32.