Everyone who follows this blog must have an inkling that I’m a sucker for local supermarkets, farmers’ markets, fresh produce, spices and such.

So yesterday when we passed the Red Mountain Supermarket in Dubai—with windows full of temptation—I simply had to go in.

Poor John is a good sport about these side trips, and even points out likely targets.

We had to wait a while to get in. There were five or six customers blocking the entrance and no amount of ahem-ing on our part was going to get them to budge. They were having a chat (actually a rather long discussion) on who knows what. A couple of customers stranded outside was of no concern to them.

But finally they moved on—and we moved in.

Oh my, what a wonderland for me. Nuts, spices, dried fruits, lollies, colourful packaging, and not a grocery to be found. You know what I mean—no processed food, no milk, no baby goods, no kitchenwares.

So I thought you liked to see a bit of what we saw and meet some of the staff. They were friendly, helpful and quite happy to have their photos taken.

Sydney Harbour is a unit of measure—rather like Belgium and Olympic swimming pools—as in how many Sydney Harbours does it take to fill up a whatever you pick?

But once you get past that thinking, the harbour is a fabulous body of water and a magnificent landscape that changes with the weather and the time of day.

And the Sydney Harbour Bridge, fondly known as the coathanger for its arched shape, is an important focal point for the busy harbour. It’s the largest (but not longest) steel-arch bridge in the world.

Lots of New Year fireworks get set off there (I must record that one day) and the bridge climb is a popular activity for Australians and foreigners alike.

I keep meaning to buy Poor John a bridge climb (they aren’t cheap) for a birthday or Christmas present (shh, don’t tell him), but I never know exactly when we’ll be around. Note to self: plan ahead.

Anyway, last week Poor John and I were on a ferry on the harbour, travelling to Cockatoo Island to see one venue of the Biennale of Sydney’s contemporary art exhibition.

Usually we head east on the harbour, but Cockatoo Island is west, near the junction of the Parramatta and Lane Cove rivers. So we went west and under the bridge. It’s the first time we’ve gone that way in a very long time.

I thought you might enjoy seeing some of the images I captured, including two shots of moonrise taken from the wharf at Cockatoo Island.

If you’re ever in Sydney, take yourself out to the island. It’s a great place to explore—you can even stay the night and go glamping (glamour camping).

We were in Sydney earlier this week—on our way to joining another overland jaunt following the Silk Road and cruising through the Stans—Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

We timed this stop in Australia’s biggest city well because we were able to spend a whole afternoon exploring Cockatoo Island and the Biennale exhibits located there.

The Biennale of Sydney is a non-profit organisation that presents the largest and most exciting contemporary visual arts event in Australia.

A biennale comes around once every two years and this year it involves five major locations across the city, as well as some one-off special-event sites. Another day we visited the biennale exhibits at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (more about that later), but ran out of time to visit Carriageworks, Artspace or the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia.

Each biennale—they started here in 1973—lasts for three months, and this one ends in early June. Amazingly, all the shows are open to the public at no charge.

There are lots of related events with artist talks, forums, family days and guided tours. One of our daughters recently did a Biennale Boot Camp, which combined a tour of the Cockatoo Island artworks mixed in with some heavy-duty exercises.

Poor John and I took it a bit easier, walking from exhibit to exhibit, but got a mini workout at the playful artwork built around old gym equipment, created by Gerda Steiner and Jörg Lenzlinger. They should feel highly complimented because I think it’s the first time Poor John ever got anywhere near a weight machine.

Sydney presented the Asia–Pacific region’s first biennale and, along with similar events in Venice and São Paulo, is one of the longest running exhibitions of its kind in the world.

Since its start in the 1970s, the Biennale of Sydney has showcased work by almost 1600 artists from more than 100 countries. Today it ranks as one of the leading international festivals of contemporary art.

The Biennale of Sydney was also the first to focus on Asia and the contemporary art of our region, the first to show Indigenous art in an international contemporary art context, and the first to present an online presence.

So stroll along with us for some of the highlights at Cockatoo Island.

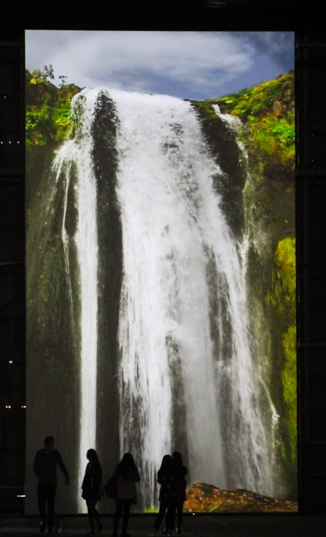

Besides the gym equipment, my favourites were the waterfall by Eva Koch the village by Randi and Katrine of Denmark, the bubble shapes by Mikala Dwyer, and many more that were sound-oriented or impossible to photograph.

The gym equipment is just plain fun—pull down to make a bubble machine work, pedal to get a skeleton to dance, hoist a leg up to bang the drum and push forward to fan yourself.

The waterfall is thunderously overwhelming. It’s a gigantic video and sound projection set up at the end of a long, tall, narrow building. You approach from perhaps 75 metres away and are immediately struck by the realism. The sound helps. It gets louder and louder as you approach. Libby, who did the Cockatoo Island Boot Camp, says she was told the soundtrack includes cascading water as well as the beating of horses’ hooves.

The village is in another long, tall space. My pics don’t quite capture the lighting or mood, but the buildings have an ancient, dark and rather sinister quality about them.

Dwyer’s bubbles are all about lightness and light. Placed in the corner of a low, darkish industrial building, the taller-than-me ‘bubbles’ captured a glow from the setting sun when we were there.

This biennale continues until 9 June. Go if you can. And in case you didn’t know, you need to take a ferry to get to Cockatoo Island (wharf 5). It’s a great way to see Sydney Harbour.

Stop back soon to see some of the biennale works shown at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

P.S. Just letting everyone know we have had three days in China with no access to the blog. I suspect my connections in the days ahead may be limited. Wish me luck

News from Nigeria has been bad over the last few weeks. More than 200 school girls were kidnapped from a boarding school in the northeast of the country. And another bomb went off in Abuja, the nation’s capital. Nineteen people have been confirmed dead—and that’s on top of the 75 who died a few weeks ago in another explosion in the busy Nyanya bus station.

It’s especially sad because I have some affinity with Abuja. It’s a purpose-built capital city, like Canberra (my home) in Australia and Brasilia in Brazil. Plus a couple of years back, we spent about nine days in Abuja getting visas needed to continue our travels through Africa.

Created in the 1960s to replace Lagos as the capital, Abuja is a huge country town (rather like Canberra).

There’s no real town centre—which we were told was intentional—so there is no place for people to congregate for riots. That’s a disturbing premise for town planning. But the city’s urban spread clearly doesn’t protect the place and its residents from terrorist attacks.

My heart breaks for the people who have to live through this sort of violence, fear and trauma.

Luckily, my memories of Abuja are quite a bit tamer and cheerier. One of my most vivid recollections is of the huge market that was a longish taxi ride from where we were staying—camping in the ‘backyard’ of the Sheraton Hotel. More about that soon.

I visited the market three times in nine days and reveled in the marvelous array and excellent quality of foodstuffs I was able to buy. And the stallholders were so friendly, helpful and informative. Language wasn’t even a barrier. I bought a couple of items I didn’t recognise and, through miming, was able to determine whether it should be cooked or eaten raw.

Gwynne, one of our travelling companions, bought a pair of tennis shoes—a little large but still okay—and Poor John bought a couple of aprons because he was tired of getting food and soot all over his clothes every time it was our turn to cook.

I unwittingly managed to irk one of the butchers. I visited the meat section on a day that wasn’t our cook group’s turn to make dinner. I told one of the butchers that I’d be back and buy from him on ‘my day’.

Of course, a few days later I wandered up and down the aisles but couldn’t spot him, so started to buy from someone else. Obviously, my foreign face was pretty easy to recognise and my original butcher chased me down (I was a few aisles away) before I spent my money in the ‘wrong’ place. Butcher no. 2 wasn’t very happy, but you can’t please everyone.

The opportunity to shop in local markets is one of my favourite tasks on an overland truck trip. We’re organised into cook groups, and take turns shopping and preparing meals. While I’m glad I don’t cook for a group every day, I could visit a farmer’s market every day. In fact, I try to food shop almost every day wherever I am.

What are your shopping habits?

P.S. If you are a food lover, be sure to visit my cooking escapades.

We’ve had a couple of glorious weeks on Australia’s South Coast, marking the Easter and Anzac Day holidays. I’ll write more about Anzac Day another time, but I wanted to show you one of the gorgeous coastal walks we took during our stay.

I reckon Australia has some of the most beautiful beaches in the world, and the South Coast has some fantastically scenic walking paths on the ridges running along the coastline.

Today four of us (and a dog) set out from Mosquito Bay, which is on the north end of the small community called Malua Bay.

I’m not sure how far we walked, but the booklet we use to find these walks—Coastal walks around Batemans Bay by Allan Tarry—predicted the round-trip stretch we did would take 110 to 140 minutes. We did it in 110 and stopped often to admire the views, take photos and let the dog have a run.

From Mosquito Bay we strolled on to Lilli Pilli Beach. There’s a bit of up and down and some roots to avoid, but overall a pretty easy walk. Then it was on to Circuit Beach. That’s another easy path except for the steep-ish downhill steps at the very end. Luckily there’s a rope ‘railing’ to hang on to.

Our last leg was to Wimbie Beach. While that stretch is classed as ‘difficult’, I couldn’t detect much difference.

On the way back, Libby and Daniel stopped for a swim at Circuit Beach. Poor John and I walked back to the car and drove round to collect them. Then we headed to Batehaven for a meal of fish and chips from Berny’s.

There aren’t any pics of the food, but there are some of the views. It was quite cloudy, so I might have to come back again on a sunnier day.

Oh, and a few words of praise for Allan Tarry. His booklet covers 39 walks between Pebbly Beach to the north and Broulee to the south. Sometime after it was published, a stretch of one walk was deemed to be on private, rather than public, property. Someone, most likely Tarry, updated every entry in handwriting.

Countries around the world celebrate Arbor Day by caring for and planting trees. Internationally, the first ever Arbor Day was organised in 1805 in the small Spanish village of Villanueva de la Sierra by the local priest and an enthusiastic community.

The custom, which was celebrated yesterday (April 25) in the United States, began in that country—in my home state of Nebraska—in April 1872. That’s when tree enthusiast and newspaper editor, Julius Sterling Morton, organised a day on which a million trees were planted.

Morton became well known in Nebraska for his political, agricultural and literary activities, and President Grover Cleveland appointed him as Secretary of Agriculture. Morton is credited with helping that department change into a coordinated service to farmers, and he supported Cleveland in setting up national forest reservations.

Which brings me to Halsey National Forest, or perhaps more accurately the Nebraska National Forest, in the state’s rolling sandhills. Established in the early 1900s, this forest was, until recently, considered the largest hand-planted forest in the world, with about 25,000 acres of trees planted since 1903.

Poor John and I visited Halsey (I still call it that) last year when we drove northwest from Kearney to visit Valentine and Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge.

It took me back 40 years when I last visited to photograph the heartbreaking ravages of a major fire that destroyed, if I recall correctly, about 40 per cent of the trees. I don’t have any of those photos now, except in my mind’s eye, but it was gratifying to see the vast expanses of forest there today.

We climbed up the current Scott Lookout Tower, which was renovated a couple of years ago. It’s only 70 steps to the top, but it gives great views over the forest. And it made me proud to remember that Arbor Day in the US started in Nebraska.

Dates for celebrating Arbor Day vary around the world and usually reflect the time of the year that is good for planting trees.

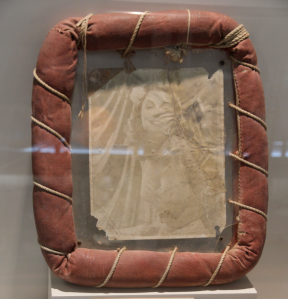

My mum loved to swim—she was even invited to train for the Olympics in the 1930s—so it’s not surprising that she loved watching Esther Williams, Hollywood’s swimming star.

I have no idea how many Esther Williams’ films I’ve watched and, thanks to Turner Classic Movies, my daughters have watched them too. With elaborate synchronised swimming routines choreographed by Busby Berkeley, these films were true extravaganzas.

But there’s another mini extravaganza linked to Esther Williams and I wonder if my mum had ever heard of it—I hadn’t until I visited the Royal Australian Navy Heritage Centre on Garden Island in Sydney.

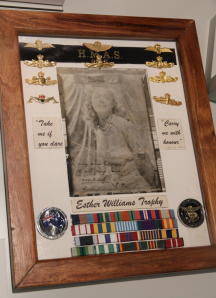

It’s the ongoing saga of the Esther Williams Trophy, and the quest to ‘rescue’ and hold her.

The trophy came to life in 1943 when Lieutenant Lindsay Brand, serving on HMAS Nizam, received a studio publicity photo of Ms Williams. A fellow officer grabbed Brand’s photo and wrote ‘To my own Georgie, with all my love and a passionate kiss, Esther’ across it.

Soon a competition was on between Royal Australian Navy units (wardrooms) and other fleets throughout the Pacific. There were five strict rules attached to the ‘captured’ trophy.

1. The battle trophy is to remain unsecured and in full view.

2. The trophy may only be removed by force (preferably of the brute variety) or by exceedingly low cunning and vile stealth.

3. Use of enlisted personnel (ratings) in any fashion is prohibited.

4. The only other restriction is against firearms and clubs.

5. Unsuccessful suitors are to be given haircuts and lodging (cells).

Perhaps the most brutish of raids was when officers of the USS Boxer attempted to retrieve the trophy from the HMAS Warramunga. Three Americans and one Australian ended up in hospital, but I haven’t been able to find out where ‘Esther’ landed.

There’s more than one Esther William Trophy. The original was battle damaged and withdrawn from use in the 1950s. A ‘battle’ or ‘fighting’ copy was created and used thereafter.

Both were retired to the Royal Australian Navy Heritage Centre after Ms Williams died in 2013. It was at her request that they be decommissioned after she died.

Commander Jason Hunter of HMAS Stuart escorted the trophy on her final voyage from Fleet Base West, presenting her to Commander Australian Fleet, Rear Admiral Tim Barrett. When receiving it, he said, ‘The Esther Williams Trophy has moved around the fleet on a regular basis. Since 1943, she has been more than just a picture to put on the bulkhead, she has provided a sense of camaraderie, something to strive for, while injecting a little fun and rivalry between units.’

It’s believed that over 70 years of existence, the trophy circulated among more than 200 ships and establishments including those of the Royal Australian Navy, the Royal Canadian Navy and the United States Navy.

I think the coolest aspects of all this—besides the fact that it is so beautifully displayed today—is that Esther Williams herself knew of the trophy and thought it great fun and that Brand did not know (until 50 years later) of his inadvertent role in the whole thing starting.

Here’s another great story about ‘chasing Esther’.

I’ll be back soon with more about the displays in general at the Heritage Centre, which is well worth a visit.

If you’re in Canberra over the next two weeks, be sure to drop in to see the current exhibition at the Canberra Glassworks.

The Tree, curated by Clare Belfrage, features 25 established and emerging Australian glass artists. Each artist was asked to create a piece that reflects our relationship with trees—from their beauty to their place in mythology to the ways they are exploited.

The exhibition continues through 8 May, and the Glassworks is open Wednesdays through Sundays from 10am to 4pm. Admission is by a gold coin donation.

I’m sharing pics of a few of my favourite pieces, but go see the artworks for yourself. The Glassworks also offers classes, demonstrations and workshops. And plenty more exhibitions are coming up.

Poor John and I were lucky enough to visit the Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge when we travelled northwest across central Nebraska from Kearney to Valentine.

Established in 1912 by President Theodore Roosevelt, this 19,000-acre refuge is part of a national network of land set aside specifically for the preservation of birds, bison and elk. So far, more than 540 refuges have been established.

The Fort Niobrara refuge is doing its job. More than 230 species of bird are found there, along with 350 bison and about 100 elk. The Niobrara River runs through the refuge, bringing plenty of water and nourishment for all the ‘beasts’.

We saw a meandering herd of bison in the refuge. Based on what I’ve read, I think we were there in the mating season—June to August. The bulls weren’t showing signs of aggression, but they were with the herd. Apparently they are solitary during other months.

Bison were also featured at Woolaroc in Oklahoma. I’m pretty sure Woolaroc has some bison on site, but we didn’t see any on the hoof. But there’s an excellent display of information about the bison’s history and plight.

The bison info is heartbreaking. No one knows exactly how many bison there were before the main slaughter began in the 1800s, but estimates range from 30 to 200 million. Travellers in the Great Plains were always impressed by the numbers of bison they saw, and guesstimates reckon there were still 60 million in 1800 and 30 million in 1830.

Bison hides and bones were big business in the later 1800s and the biggest year was 1874, when more than seven million pounds of bones were shipped to eastern markets.

It makes me proud that Nebraska is doing its bit to keep bison on the planet. Oh, and we loved seeing the prairie dogs too.