We were striding toward a departure gate yesterday in Sydney’s Kingsford-Smith Airport and suddenly I realised my old friend was gone?

No, not Poor John, but my 10-year-old watch!

Oh crap! This was a blow. We were heading off for six weeks in India and the trusty watch I bought in 2003 had vanished.

Poor John reckoned I’d left it at check-in or put it my pocket after I noticed it was out by a couple of minutes and took it off to reset it. But I clearly remembered checking the time at least 10 minutes after resetting it.

I reckon the pin on the watchband fell out and the watch simply followed it to the terrazzo floor.

Poor watch, and I never even thought to give it a name! I bought it on around-the-world travels when I searched and searched and searched for a water-resistant watch with decent-sized numbers. I found this one in Chichester in the UK. Cost me 27 pounds.

Since then I’ve worn it travelling overland through at least 60 different countries on all seven continents. It didn’t do much except tell time. If I had to write a missing watch notice it would say—‘gold-coloured watch, has largish face, second hand and stretchy wristband, keeps good time’.

It started getting a little unreliable before our last overland trip in South America. It would run fine for a while and then suddenly lose an hour for no apparent reason. We changed the battery but the behaviour continued.

It took me a couple of weeks to figure out that it only lost time when I took it off for longer than about 10 minutes—yes, I wore that watch to bed even though it didn’t light up in the dark. I tested this theory a few times and was really quite sure this was the reason, because it wasn’t a movement-operated watch.

Poor John just laughed at this theory and urged me to buy a new watch, which I did a couple of days before we left for South America. I put the old watch on notice and the new watch in my backpack. It stayed there for the whole trip, and my old gold number ran just fine.

Last week it lost an hour when I inadvertently left it on the bed for most of a morning, but otherwise it had been completely fine for months.

Yesterday it jumped or was accidently pushed from my arm! I’ll never know if it smashed to the floor or bounced and was picked up by a new owner. I wonder if it will run for them?

Poor John said, I don’t suppose you thought to bring the new watch?

Well yes, I did, and pulled it out of the backpack where it had lain for months and put it on.

It’s fashionable—a wide red wristband with a buckle, silver finish—and so far the time seems accurate. The numbers are big enough I should be able to read them from across the street. Plus, there’s a second hand and a light.

But I reckon a watch this big should be like Poor John’s and tell me the temperature, altitude, direction, day of the week, month and where I am in the world.

Maybe I’ll buy one of those next time.

P.S. I discussed my watch-losing-time-when-off-the-wrist theory with the woman who sold me my new watch. She figured it was as good a theory as any. 😛

Poor John and I made a very timely stop in Sydney this weekend on our way to India.

Sculpture by the Sea is on until 10 November, with scores of exhibits displayed on the coastal walk that stretches between Tamarama to Bondi beaches. It is the largest free outdoor sculpture exhibition in the world.

We walked down to Bronte Beach early this morning to start our tour before the hordes appeared.

I’ll do another general post on this event, but I simply had to devote an entire post to the most amazing sculpture of the lot.

Created by a Lucy Humphrey, Horizon is a huge, mirrored sphere perched high on the rocky ledges overlooking Tamarama Beach. It’s probably about five feet in diameter, and it’s rounded surface captures the movements of the sea below and the sky above.

It’s absolutely breathtaking and we stood for a long time, savouring the ever-changing views.

Ms Humphrey is one of three winners of a Helen Lempriere Scholarship. These annual scholarships are open to all Australian sculptors who enter a work in Sculpture by the Sea. Each winner receives $30,000, which can be used to advance their career through study or research.

And now I’ll let the pictures do the talking.

Apologising in advance if this is too much information for some people, but this has to be shared for the womenfolk.

Ever since I wrote a piece the other day on what to take on an overland trip, my ancient bra has been reminding me that I didn’t give it enough attention.

Bras remind you by being extremely uncomfortable. Suddenly the shoulder straps cut into or slip down your shoulders, or the flab under your armpits decides to ooze out over the bra sides, or an underwire cuts its way to freedom and stabs you in the chest. All most unpleasant reminders.

So let’s talk underwear and travel.

If you are a normal size—whether bust or waist or bum—you can stop reading now because you will be able to buy bras and other undies anywhere in the world. You’ll also be able to buy a bikini top off an umbrella at the beach in Brazil.

But assuming that you have your own unique size and shape, please read on. I’m busty, so this post will favour my own uniqueness-of-shape.

————————–

I usually travel with four or five pairs of knickers and two bras, although I took three bras on our 12-month overland that covered Africa, a bit of the Middle East, and a final side-trip to England.

On that trip, I took the oldest bras I owned. I figured they’d die on the trip and I’d be able to replace them somewhere along the way. At least one survived and I was wearing it today and it’s the bra that reminded me that I should kill it now.

But the other two died en route, and I was delighted to be able to replace them during our two weeks in the UK at the end of the trip. I have no idea if I would have been able to replace in any other the other 30 countries we visited over those 12 months. I never needed to look, but I did see plenty of bras dangling from big umbrellas throughout Africa.

But in the UK, Marks and Spencer had a great lingerie department staffed by keen and competent people. The lass who served me knew her business. She measured me and advised on size, shape and fit. I bought four bras and a couple of pairs of matching knickers. It was the first time in my life I’d ever bought knickers to match a bra. I highly recommend shopping for bras at Marks and Sparks (our nickname for them) if you ever have the chance.

But that was almost four years ago, and those four bras are getting tired and weary, and the knickers have given up completely.

So I’m back in the bra market, which is proving to be a sad place to be. 😦

I was already in the bra market last year when we were in Ecuador. So when I saw a lingerie shop in Quito, I popped in—full of hope.

Got any underwire bras with a D or DD cup and so-many-centimetres around (some things should stay private), I asked?

Her look of shock and concern was such that I might as well have asked if she would hand over her first born.

But she reluctantly rummaged around and came up with an ugly brown C-cup option. This should be good, madam, she said!

No, it won’t be okay, I said, adding that if I put in on, I might never get it off or ever breathe again.

She thought I was being difficult. I knew she was being sales-oriented and hopeful, so Poor John and I bowed out and went on our way.

I tried a lot of other lingerie shops in South America, but never found anything that would come anywhere close to fitting me. I was surprised because there are plenty of women on that continent who are my size or bigger.

So I started my search again in Australia last week. I thought it might be easier or more satisfactory. I was wrong, sort of.

I was in a huge shopping mall and stopped in a shop that was a branch of a national lingerie chain. I was thrilled to see that the saleswoman was bustier than me. Not a little bustier, but hugely bustier. You’re exactly the person I was hoping for, I said.

I tried on a few bras, but nothing came close to fitting. Rather like being back in Quito except that the saleswoman spoke English and really knew her business. After I tried on a few rejects, she told me quietly, and on the side, that none of the bras in this shop would fit me. She told me where to go—a small independent specialty lingerie shop—saying it was the only place that could fit her too.

Obviously, we busty gals need to stick together. And we certainly cannot leave finding a bra that fits to chance.

So if you are bustier, buy your bras when and where you can. They most certainly are not something you can hope to find everywhere else in the world. Ask questions and directions, and let anyone who is helpful know how much you appreciate their efforts.

I still haven’t made it to the specialty shop, and still haven’t made a purchase. I did try briefly in a huge department store that was having a huge sale. Poor John was tagging along and looking a little lost, but not unaccompanied. The saleswoman came up and asked if HE needed help. He said no, but pointed to me. And she smiled, shrugged and walked off. Got to love attentive SALES people.

P.S. Knickers are rather easier to find, but I still take what I need from Australia. All my traveling ones are made of merino wool. They’re lightweight, comfy and dry quickly.

P.P.S. Feminine products can be a problem too. Unless you know the language of the country you’re in, you can’t always tell what you’re buying. Take supplies with you.

New flash

Yesterday, while we were delayed for many hours in the New Delhi airport, Poor John pointed out a Marks and Sparks outlet with a wall of bras on display. The saleswoman was most helpful and brought out the ONLY bra that might be right. It was perfect and I bought it—$30. I am a very happy camper.

I was completely astounded by the incredible number and variety of butterflies fluttering around Iguazu Falls.

We first saw them on the Argentine side of the falls. We arrived early in the day when the butterflies are resting on plants and railings of the walkways that lead to the falls.

As the sun dries their wings, they start to fly about. Sometimes many types come together in what are called assemblies, with literally hundreds of individuals in close proximity.

Most of these photos were taken on the Argentine side. The railings in the background are mostly from the Paseo Garganta del Diablo, a 1-kilometre-long trail that takes visitors directly over the falls of the Devil’s Throat, the highest and deepest of the falls. We saw a lot of other wildlife on our walks through the falls, but I wanted to devote this post to butterflies only.

If you ever get to Iguazu, go in the morning, take your time and watch where you step.

P.S. I’ve been able to identify only a few of these magnificent butterflies (and probably a moth or two). I found a website that shows there are almost 800 different types of butterfly at Iguazu Falls, but there were pictures of only about 30. Let me know if you can ID any of them.

P.P.S. A big thank you to Roberto R. Greve, a butterfly researcher, who has kindly identified many of these. Most appreciated. Click on or roll over a pic to see added info.

People often ask me what I usually take on an overland trip.

Almost two years ago, I wrote a post on what I took for the six-month jaunt from London to Sydney. We travelled across great swathes of remote Asia, so I carried more than I probably needed, just to be sure.

So now, having done road trips in Africa (twice), Asia (once), South America (twice) and Australia (lots), I realise that I can buy almost everything I need along the way, so there really is no longer the pressing need to take a three or four-month supply of things.

For our most recent South American trips, with one lasting six months, I took a 65-litre Berghaus backpack with its attached 15-litre daypack. I also took a 15-litre MacPac daypack and my camera case, which held a 600D Canon with two lenses. Poor John takes a similar size backpack and daypack, but no second daypack. So he gets to carry the camera. 🙂

Last time, my Berghaus combo weighed in at 14.5 kilos. Tucked away in it was seven packets of TimTam biscuits (1.2 kilos) for presents, a glass jar of Vegemite (500 grams plus weight of jar), a plastic tub of peanut butter (375 grams plus tub) and 6 paperback books. So my actual gear probably weighed less than 12 kilos.

It weighed 14.5 kilos when I headed home, but a lot of that was Libby’s skirt.

What to take to India

We’re heading out soon on a six-week road trip in central India, focusing on national parks and plenty of camping. We’re also spending a few days with a dear friend in Delhi, so I am taking at least one dressier outfit.

Here’s what I’ll be taking for that trip. I’ll note anything I’d do differently for a much longer trip. Tents and all meals are provided for this trip and I haven’t yet decided whether to take much/any Vegemite.

• 1 three-season sleeping bag (need a four season for more extreme temperatures)

• 1 Therm-a-Rest sleep mat—buy the best, you won’t regret it

• 1 merino sleeping bag liner for the cold (take a silk one too if it will be super hot)

• 1 travel pillow

• 1 pair rubber thongs—flip-flops, not underpants

• 1 pair runners/sneakers/whatever you call them

• 1 pair sandals or dressy flats

• 2 bras (3 for longer trips)

• 4 underpants

• 2 pairs long pants, one with zip-off legs (3 for longer trips) (no jeans because they take forever to dry)

• 2 pairs shorts (3 for longer trips)

• 2–3 sleeveless or short-sleeve merino tops

• 3–4 long-sleeve merino tops of varying weights

• 1 thermal leggings

• 1 skirt

• 1 blouse

• 1 sarong (indispensable, follow link to see why)

• 1 bathers/swimmers/swimsuit

• 1 belt (to hold up my shorts)

• 2–3 pairs sport socks

• 1 pair thermal socks (2 for longer trips)

• 1 travel towel

• 1 Goretex rain jacket with hood

• 1 travel umbrella

• 1 pair lightweight but warm gloves

• 1 lightweight but warm beanie

• 1 head torch with 1 set spare batteries

• 1 electric toothbrush, extra brush and charger (indispensable)

• 1 tube Colgate Sensitive toothpaste (this is something I take with me)

• 2-month supply of blood pressure tablets

• small selection of antibiotics, water tabs, cough lollies etc

• handful of plasters (bandaids)

• minimal toiletries (easy to buy replacements)

• 1 small notebook (easy to buy replacements)

• 1 Swiss Army knife (with scissors)

• 1 heavy-duty nail clipper

• 1 sunscreen

• 1 bug repellent

• 2–3 pens

• 1 soft-pack tissues

• 1 sewing kit (with rubber bands wrapped around it)

• 1 packet zip-lock bags

• 3 waterproof bags in various sizes

• 1 Canon 600D camera with 2 lenses, case and charger

• 1 Kindle and charger

• 2 plug adaptors (both 2-pin round)

• 1 external hard drive (for back-ups)

• mobile phone, iPod, MacAir laptop (in Hard Candy case) and chargers.

Some basics

All my merino tops are black. My shorts and pants are khaki. People probably wonder if I ever change clothes, but I swear I do every couple of days.

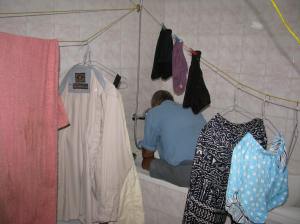

Obviously, with such a limited wardrobe, I need do laundry along the way, or ‘send it out’. I have to be careful because my merino clothes will shrink if run through a dryer, so I tend to do my own washing at every opportunity.

I’ve done laundry in bathroom sinks, bathtubs, showers, buckets, washtubs and in rivers. I never take any white clothes and I try to avoid buttons. Snaps are good.

When we’re in a little hotel or hostel, I always ask where the clothesline is. There’s almost always one—somewhere.

Every overland truck I’ve ever been on has had a clothesline and often a selection of clothespegs. I’ve always been able to buy laundry powder and a scrub brush en route. I think it was on the border between Mauritania and Burkina Faso that I got rid of the last of my small change by buying six small sachets of laundry soap.

Sunscreen and bug repellent are sometimes hard to find or are super expensive, so it’s worth taking a good supply. Same goes for women’s hygiene products.

On the other hand, most toiletries are for sale everywhere, so if you don’t have a brand preference, you’ll always find something appropriate. I take small bottles of shampoo, conditioner and body wash. I use large bottles at home and decant into small bottles that I buy at a hardware store. Cosmetic stores and pharmacies charge way too much for what they call ‘travel bottles’. My main must-take item is Colgate Sensitive, which is sold everywhere in Asia but almost nowhere in South America. That said, Bolivia has the cheapest toiletries in South America. Buy up big when you’re there.

My toothbrush confession

Electric toothbrushes are an anomaly. I can’t live without my electric toothbrush and I rarely have to do so.

One of mine (an Oral-B) conked out in Namibia during our 11-month overland in Africa. This was a serious setback, but I managed to buy a replacement the next day in a smallish shopping centre in South Africa. Eighteen months later that one conked out in Kazakhstan and I bought a replacement the next day in a huge market.

Last year and at Poor John’s suggestion, I upgraded to a schmick Phillips that is dual voltage and holds a charge for three weeks. I took both two bases to South America, but forgot the charger on the most recent jaunt.

The only thing that could have been worse would have been to forget my passport.

Seriously, my electric toothbrush is an important part of my life. My mother drummed the you-only-have-one-set-of-adult-teeth-in-your-life mantra permanently into my head.

So I went toothbrush hunting in Rio. I spent hours and days hunting and finally found, in a small shop in a huge shopping centre, a battery-operated one for $22 and an electric one for $140. These were the only motorised toothbrushes of any kind I found on the entire continent.

Reluctantly I bought the battery-charged one and then followed Poor John’s advice. He’s a true lateral thinker and offered a brilliant suggestion. I had two bases, each with a three-week charge for two brushings a day (or a total of 84 brushings of two minutes each). We were going to be away for 75 days (or 150 brushings), so Poor John said use the battery-operated version in the morning and the heavy-duty Phillips at night.

You know it worked. I even got back to Australia with a couple of brushings left in the Phillips.

You can bet I’ll never forget the charger again. I firmly believe you can buy most things in most places in the world. Electric toothbrushes fall outside that theory.

P.S. Remind me to tell you how I worked around losing my camera-battery charger out of the back-end of a 4W-drive vehicle as we bounced across the Sinai desert.

P.P.S. Sorry if I got side-tracked on the toothbrush. Happy to answer questions on what to take.

P.P.P.S. And if you’re feeling hungry, please check out my food blog Cooking on page 32.

We’re not big gift buyers when we go on our overland trips. We don’t even buy much for ourselves.

It’s really a matter of logistics. You may have plenty of room in your locker on an overland truck, but there’s always that problem of wedging your purchases into a backpack to get them home.

Luckily our daughters are used to getting tiny, lightweight presents—exotic necklaces and earrings, handmade Christmas decorations, aprons, fridge magnets and more earrings (including lots of really deluxe ones).

So earlier this year, when we were heading out on our second South American overland in less than a year, I realised that I’d run out of ideas. I decided to throw out at least one possibility.

Libby, who works in the world of art and museums, is especially interested in wet specimens (you know, icky stuff floating in jars) and textiles.

Textiles had to be the go. I remembered the colourful skirts we saw on women throughout Peru, as well as the ones we saw being worn on an island in Lake Titicaca.

Lib, hon, do you want an embroidered skirt from Peru? Oh wow, did her eyes light up.

And so the search began.

As soon as we arrived in South America, Poor John joined the effort by constantly reminding me to look for a skirt.

In spite of this conscientious nagging, I didn’t even think about skirts for the six-plus weeks we were in Brazil. I was after a Peruvian skirt and I’d have a couple of week to look there.

I began the search as soon as we crossed the border. I traipsed through markets, using scribbled sketches and hand signs to try to explain what I wanted.

We visited the huge market in Pisac. I asked our guide’s sister, who runs a stall there, where I could find an embroidered skirt. She rolled her eyes and shrugged. And then it dawned on me.

The women in Lake Titicaca had said they decorated their own skirts. And these masterpieces are developed over their lifetimes.

Hmm, now what? I hadn’t even seen a plain skirt that needed decorating.

I started making the rounds of all the shops in Cusco and finally found a magnificent skirt in an elegant shop that specialises in works by local artisans. We’d shopped there on our first visit, buying the girls lovely, but small textile pieces.

Poor John saw the skirt first, on display in the window. I saw the price tag—US$400. Now I have to admit that this skirt was worth every cent. The design was elaborate and the work was exquisite. Not a stitch out of place, beautiful colours, a truly breathtaking item.

But Libby would have shot me if I’d bought it. I knew she would prefer a rustic skirt that would give her some insight into basic Peruvian textiles and their design and construction.

I asked the saleswoman where I might buy such a skirt. She confirmed that most women make their own, although admitted that she—as a working woman—had bought hers in her village.

So I thanked her and took a picture of the skirt.

We were told about a large handicraft marketplace, so decided to walk down there and see what we could find. Mostly plain and poorly made skirts were hanging outside the first couple of stalls.

Okay, making headway. At least ready-made skirts existed. We cruised up and down the acres of aisles and stalls, all selling much the same stuff.

We finally made it to the very back of this warehouse-like structure, where there was a small café. The waitress invited us over in English. No, we didn’t want anything to eat or drink right now, but is there anywhere we could find a skirt?

She pointed across the aisle from us and said, I think that woman has skirts.

She led us over, explained the quest and the next I knew we were being shown a fabulous skirt, just exactly what I was looking for. It was wool, huge and heavy. The workmanship was painstaking, but simple.

The skirt weighs almost 4 kilos and the waist is large enough to fit the circus fat lady. I told the saleswoman that Libby was quite small, but she showed me how the skirt could be one-size-fits-all. Nothing like a huge built-in belt.

So after some cursory haggling, I bought that skirt.

And it’s truly perfect. As soon as I presented it to Libby back in Australia, her museum voice asked if I’d declared it in customs. Well no, I said, it’s only wool.

Only wool! Mum, she said, wool is like lollies to moths and other insects. And she promptly stuffed it in a couple of plastic bags and crammed it into her freezer for a couple of weeks.

So I had to wait until it came out of the freezer so I could share this story.

P.S. Petra got a well-thought-out gift too—a cookbook on ceviche. It explains the history of this classic South American dish and is loaded with recipes. It’s written in both English and Spanish, which should come in handy for someone who is planning to teach languages to high school students.

I promise to share the page-32 recipe from that book on my cooking blog.

Approaching the Inca Bridge. See what looks like a little gap in the lower centre? It’s actually 6 metres across

Once you get near Machu Picchu, you hear about all sorts of Inca trails.

The biggie, of course, is the Classic Trail that so many people walk (actually they mostly climb steps) for several days to arrive, before sunrise, at the Sun Gate entrance to these ancient ruins. Trust me folks, the Sun Gate is overrated. It just sounds impressive, and you can’t really see the sun rise from there.

Then there are the 4-to-5-day Lares and Salkantay Treks. Poor John and I did the Lares Trek (tough but highly recommended) the first time we visited Machu Picchu. The second time we took the train and found lots of other fascinating ruins to visit during the four days that we weren’t scrambling across rough terrain.

But almost everywhere you go in Peru, guides point out bits of Inca trail that crisscross all over the empire.

It’s not surprising because in the 100 years prior to the Spanish Conquest of what is now Peru, the Incas built more than 22,500 kilometres (14,000 miles) of road. The roads were up to 5 metres wide and were often paved. Very steep sections were bounded by stone walls to keep people from tumbling over the edge.

The Incas used these roads to move their army and goods about and to protect the empire. Young men ran messages to and from the capital, Cusco. Llama trains collected food from farms and moved it to cities and to storehouses along the road. It is said that some storehouses could hold enough food and supplies for 25,000 people.

On our second visit to Machu Picchu, Poor John and I took a stroll on one of these roads. This particular one was narrow—more of a track—and probably served as a secret entrance to the ruins.

The path is fairly level, paved with stone and clings to the side of a mountain. Some stretches have been cut into the cliff face and edged with low stone walls. It’s a huge drop for anyone who loses their footing.

It gave us an entirely different view of Machu Picchu. We could see the river and community below, and get a better view of mountains in the distance. There’s plenty of lush cloud-forest vegetation as well as lichens on the cliff face.

And best of all—you come to the Inca Bridge. Well almost to the bridge. There’s a barrier a couple a hundred metres from the bridge—designed to protect us from ourselves and stupidity.

The Incas intentionally left a 6-metre (20-foot) gap in the bridge as a security measure. The drop below the gap is almost 600 metres (1900 feet)—more than enough to make the trail impassable to an outsider. When necessary, the gap could be bridged with tree trunks.

From the barrier and for quite a while before we reached it, we could see the tree-trunk bridge and the trail extending far beyond on the cliff face. In the pics here, take note of the faint line of vegetation that runs to the right along the side of the mountain. That growth marks where the path continues—only the most foolhardy would attempt it now.

Some time ago, a tourist crossed the bridge and had a ‘go’ at trekking on. Sadly, they fell to their death. 😦

Officials are careful now to avoid a repeat of such a catastrophe. A rustic timber barrier has been erected to prevent people from going down a very steep stone staircase and approaching close to the actual bridge. Plus there is an attendance system where the trail begins. As we entered, we had to sign a ledger and note the time we arrived. It was the same when we left. From this check point, we could look back at the terraces on Huayna Picchu.

The trail isn’t overrun with traffic, and I highly recommend making the effort to visit this breathtaking spot. It takes no more than an hour to go and come back, unless you dawdle, which of course we did.

There are probably a bazillion pictures of Machu Picchu online, and now there will be more.

Poor John and I have been lucky enough to visit these ancient Inca ruins twice in less that 12 months, and we’ve been completely impressed both times.

Last year we spent three days scrambling almost 30 kilometres on the up-and-down Lares Trek to get there. This time we cheated and took the train.

There’s a lot of uncertainty about Machu Picchu and its reason for being. It’s often referred to as the Lost City of the Incas. Some say it was a sacred religious site and perhaps where human sacrifices were ‘groomed’ for their doom. But more recent research has led most archaeologists to believe it was an estate for the Inca emperor, Pachacuti.

Most likely we’ll never know the real truth, but that doesn’t keep us from enjoying the remarkable structures and landscapes that create Machu Picchu.

So here are some of her details (I always think of locations as female).

Introducing Machu Picchu

First off, Machu Picchu is one of South America’s most important and most visited archaeological sites. Only 2500 visitors are allowed every day (and only 400 to adjacent Huayna Picchu), and there would be many more if the rules allowed it.

It wasn’t always so heavily visited.

A friend, who lived many years in Brazil and Chile, visited Machu Picchu twice in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Back then, he and a couple of busloads of people travelled from nearby Aguas Calientes, which sits below the complex, to the entrance.

Machu Picchu (meaning old pyramid in the local Quechua language) is the name of the archaeological site and the mountain that rises behind it. The mountain looms over a loop in the Urubamba River, and is surrounded by that river on three sides.

Built about 1450, the city is located on a saddle between Huayna Picchu and Machu Picchu. Its three main structures are the Intihuatanai (Hitching Post of the Sun), the Temple of the Sun and the Room of the Three Windows. They are part of what archaeologists call the Sacred District.

The Sacred Plaza, which is near the main temples, is 2453 metres above sea level. This lofty position means the city is often misty, and its wet season extends from October to April.

The site is divided into two sectors—urban and agricultural. The urban sector has two levels with the Sacred District sitting higher than the warehouses. Up and down the hill, and across the way on the sides of Huayna Picchu, are scores of terraces for crops.

The main buildings have the classical Inca architectural style of polished dry-stone walls. Doors and windows are trapezoidal and tilt inward from bottom to top, corners usually are rounded, inside corners often incline slightly into the rooms and L-shaped blocks are often used to tie together outside corners of structures.

The Incas were masters of this technique in which blocks of stone are cut to fit together tightly without mortar. In many places, the fit is so perfect that not even a blade of grass can be inserted between stones.

Peru is prone to earthquakes so this style of construction allows the walls to move slightly and resettle without collapsing.

No matter how well it is built, Machu Picchu was abandoned after about 100 years—no one knows exactly why—but it happened about the time of the Spanish Conquest. It’s possible that the residents died of smallpox brought by the invaders.

The invaders may have brought disease, but at least they didn’t bring their scouts to the region. Unlike most Inca structures, Machu Picchu was never found or visited by the conquering Spaniards, meaning it remained reasonably intact. (The Spanish had a habit of dismantling existing structures to make churches, houses and other buildings.)

In 1911, Hiram Bingham, an American historian and lecturer at Yale University, brought the first news of Machu Picchu to the outside world. He continued to visit and excavate at the site until 1915.

Over time, local intellectuals began to object to Bingham’s work, and local landowners accused him and his team of stealing artifacts and smuggling them out of Peru, which is exactly what they were doing.

There was a long-running dispute between the Peruvian Government and Yale University, which held the artifacts. An agreement was reached in 2010 and, by late 2012, Yale had returned all of the massive collection—thousands of items—to Peru.

In 1981, Peru declared more than 300 square kilometres surrounding Machu Picchu as a ‘Historical Sanctuary’. Two years later, UNESCO designated it as a World Heritage Site, saying it was ‘an absolute masterpiece of architecture and a unique testimony to the Inca civilization’.

A few years ago, Machu Picchu was also voted one of the New Seven Wonders of the World in a worldwide internet poll.

Our visit

On both visits, we’ve arrived at nearby Aguas Calientes the night before our trip around the ruins. There are no roads to Aguas Calientes—you can reach it only by train or on foot.

Our hostels have had comfy beds and brilliant hot showers, meaning they know how to cater for people who may have trekked a couple of days to get there.

Not that we ever got much sleep in the hostel. Odon, our guide on both occasions, always reminded everyone how important it is to reach Machu Picchu before the gates open at 6am. Of course he’s right because it gives you an hour to look around before the sun rises and everyone else swarms in.

He also reminded us to bring a small daypack (big packs aren’t allowed) with water and snacks. You aren’t supposed to eat in Machu Picchu, but there are a few places where it’s allowed and Odon pointed those out later. He told us that on-site prices are ridiculous—a bottle of water is US$10 and lunch is US$49.

So by 4am we were standing in the queue for the bus with everything we needed, including our paperwork—our round-trip bus tickets, the entrance tickets and our passports.

The timing was good. We weren’t going to be on the first bus, but definitely on the second. As an aside, it pays to stay in a hostel near the bus stop, so you can take turns running back to grab some of the free breakfast that gets served from about 4:45. Shops near the bus stop also sell food and drinks.

Buses start setting out about 5:30 and take about 20 minutes to climb the narrow, steep, zigzagging road to the top.

Odon knows Machu Picchu well. He’s been guiding there for about a decade, plus he, like all guides in Peru, has had formal training.

Both times, he led us through the sprawling complex, explaining as we went, with our destination being a prime spot to watch the sunrise. We were especially lucky on our second visit with clear skies. Machu Picchu is prone to clouds and mist.

After sunrise, we had about another hour with Odon, and then we were left to explore on our own.

On our first visit we headed to the Sun Gate. I confess that about 20 minutes short of it and after struggling up what seemed like a million steep uneven steps up, I sent Poor John ahead to finish the job. I’d already spent three days on uneven terrain, and while I’m fine going up, I’m crabby coming down.

He Who Walks Everywhere covered that last distance in about 20 minutes—there and back—while I would have taken at least 40. And he assured me that I hadn’t missed anything special. I’m sure he was quietly delighted that he didn’t have to listen to me whinge all the way back.

We tackled the Inca Bridge on the second visit. It was fantastic.

I’ve been researching, fiddling with and writing this all day and I’m keen to share it.

I’d been in Cairo for about a month when I was invited to my first wedding. It was a lavish affair with lots of people, joy, laughter, music, food, belly dancing (a talent which comes naturally to all Egyptians) and loads of colour.

Egypt really isn’t known for her colour—unless you’re in the ancient tombs or fond of the dun brown dished up by the Sahara Desert—but she sure knows how to dress up for an important occasion.

Back in 1976, when I first arrived, many of Cairo’s festivities were liberally decorated with tent hangings. These enormous appliqués—with their bold colours and geometric designs—were used to create the walls and ceilings of celebratory spaces.

Even then, I knew tentmaking was an ancient craft. I’m guessing it started with nomads who wanted to bring colour and texture to the interior of tents pitched in the midst of desert landscapes.

But these days, handmade tent hangings are being replaced with acres of el-cheapo pre-printed fabric, and that change and a lack of appreciation for the skill needed to create the appliqués are killing the art form.

In the late 1970s there were about 45 master tentmakers on Sharia Khayamiya, the tentmaker street in old Islamic Cairo. Today there are fewer than 20.

But master quilter and friend, Jenny Bowker, is working hard to ingest new life into the craft and find new markets that will foster a healthy future.

And the folks in Canberra are lucky she’s sharing her crusade with us.

As part of celebrating Canberra’s 100th year, Jenny, the Canberra Quilters and other donors have joined together to bring two master tentmakers from Egypt to Australia for a program of displays, demonstrations and classes.

The fun started last weekend, when master tentmakers Hany El Sayed and Ekramy Hanafy wowed the crowds at the Egyptian Embassy’s Open Days. Both men learned their craft as children, and how they are passing the skill on to their own children.

Ekramy explained how a tent hanging comes to life from initial pattern to colour selection to construction to completed product, and Hany described the appliqué he created to mark the revolution of 25 January 2012 that saw Hosni Mubarak ousted from power.

The Open Days included a display of about 40 appliqués, including some of Jenny’s magnificent quilts inspired by her life in Egypt from 2005–09.

I feel blessed to have seen these displays and equally blessed to own about 12 small tent hangings purchased when I lived in Egypt in the late 1970s.

Jenny feels somewhat hopeful about the craft. The American Quilter’s Society has signed a three-year contract with 18 remaining tentmaking shops to provide works for international exhibitions.

Thank you Jenny for all yours efforts on behalf of the tentmakers of Egypt. If anyone is interested in knowing more about Jenny and her amazing work, please check out her website, including the images of her incredible quilts.

More exciting news was shared in a comment below. A film, titled The Tentmakers of Chareh El Khiamiah, being produced. Find out more at their website.

Nothing like a cannons-blazing rendition of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture to bring everyone to their feet for a standing ovation.

And that’s exactly what a packed house did today at the concert presented by the Canberra Symphony Orchestra with the Band of the Royal Military College, Duntroon.

Two hours of gifted musicians playing strings, brass, woodwinds, percussion and keyboards was pure magic. In fact, that’s what the event was called, The Canberra Weekly Matinee Magic, Strike up the Band!

According to Nicholas Milton, the orchestra’s personable chief conductor and artistic director, the collaboration between the two musical groups was supported generously by Nick Samaras, founder and publisher of the Canberra Weekly, a free magazine.

The concert opened with a rousing fanfare, followed by Gershwin’s Strike up the Band. Then on to Coates’ Dam Busters March.

The rest of the first half featured Strauss’ Thunder and Lightening Polka, Walton’s Crown Imperial (played the way it was originally written), Sousa’s Washington Post, Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance No. 4 and, finally, the Respighi’s moving Pines of Rome.

No doubt about it, we could hear the troops marching in throughout the Pines of Rome and, during intermission, everyone agreed it was the standout number of the first half.

If you believed the program, there were only three numbers after the interval—Suppé’s Light Cavalry Overture, Sousa’s Stars and Stripes (complete with piccolos) and the incredible 1812 Overture with accompanying ka-booms.

Most likely you know some of the ending—da-da-da-da-da-da-da-boom-boom!

There weren’t real cannons, but it sounded like it. And then the standing ovation. The applause, cheers and foot stomping were almost as thunderous as the cannons.

And they got the desired result—encores. The Gershwin medley included I’ve Got Rhythm, one of my favourites. Then there was the final number, the rousing Radetzky March, which had everyone clapping to the music (which is what you have to do for that piece).

Milton, who is a gifted violinist as well as the agile conductor (he’s a lot of fun to watch), tried to convince us that they hadn’t rehearsed this march, but I think he was fibbing. What a great note to end on—literally.

If you are anywhere near Canberra on 30–31 October, make a diversion to see the orchestra and a 300-strong choir perform Carmina Burana. The performance is a centenary gift to Canberra from the Embassy of Federal Republic of Germany. I recommend booking early.

I’d be there, but we’ll be in India.