Argentina is well known its excellent wines and we had a chance to try them first-hand when we camped in Cafayate in the north.

While Mendoza is the country’s biggest wine producer—making about 75 per cent of the annual output—Cafayate is a more intimate and relaxed way to visit wineries.

Soon after arriving at the campground, Poor John and I headed in to town and the Museum of Wine. Located in an old winery, this museum is a tribute to the wines of the area. It opened fairly recently and it used to be free to enter. Admission now is rather expensive, especially considering that you don’t even get a taste of wine, but it was still interesting to read about the region and see the old wine-making equipment.

They are quite proud of the fact that, at 1750 metres, Cafayate has some of the highest vineyards in the world, which they claim helps them to produce more complex wines. They also credit their 340 sunny days per day.

Torrontés is one of their claims to fame. This grape variety, brought from Spain many years ago, is used to make a white wine that fools you. It smells sweet and fruity—almost like apple juice—but has a lovely dry finish.

I got to taste it the next day when we visited the Nanni Winery. Cynthia offered four wines for tasting—torrontés, a rosé, a red (tannat) and a late harvest white.

I usually don’t care for sweet or dessert wines, but that late harvest white blew my socks off. It reminded me of the sensational icewine I tried in Toronto. I didn’t buy a bottle, simply because I knew it would be impossible to keep it cold, but I can still savour the taste.

I did buy a bottle of the tannat, which is tucked away in my locker for a special occasion.

Everyone did some wine-tasting on our second day in Cafayate. Those who hired bikes to travel farther afield were challenged by a 6-kilometre hill they had to ride up. They swear the ride down made it all worth it, but I have my doubts. 🙂

There’s a quick and surefire way to upset an overland driver? Just call his/her pride and joy—their baby—a bus instead of a truck.

The bus versus truck usage has been an issue on all of our overland journeys. I’ve seen drivers—even big guys—cringe, gnash their teeth, sweat, cry and convulse when the B-word is mentioned in relation to their baby. It grates on me too.

It’s a truck, not a bus, is the ongoing cry.

Actually, it confounds me how people can make the same mistake over and over again. We’ve all learned to say please and thank you without missing a beat. Surely it’s not that hard to learn to say truck instead of bus?

Amusingly, our current overland journey has had a small ‘penalty’ for saying the B-word. Offenders get to carry/wear Hippy until someone else utters the forbidden three-letter word.

I’m guessing that at least three-quarters of the passengers on this trip have escorted Hippy at least once. Some seem to have him all the time.

No doubt about it, Hippy is adventurous! He’s done a variety of extreme sports, been to fancy restaurants and provided modesty on the salt flats of Bolivia—always smiling his special smile.

But his rambunctious nature has been harmful to his health. We’re on our second blow-up Hippy. I wonder how many Hippy brothers Sammy has tucked away in the cab of the TRUCK because we’re due for a new one?

As expected, neither Poor John nor I have had a turn with Hippy. We learned all about truck versus bus terminology in Africa—and the lesson has stuck. Thank goodness.

When you spend a lot of your time riding around in trucks, events such as birthdays and public holidays are a chance to bring out our creative and rowdy sides.

Halloween was a perfect opportunity for us to reel out of control. Our hostel in La Paz, Bolivia, was just around the corner from fancy-dress street and not far from alcohol street, so a Halloween plan was soon in place.

Everyone had to draw a ‘victim’s’ name from a hat, and then buy a costume for that person to wear on Halloween. Our spend limit was 50 Bolivianos, or about $7.

You don’t need to know details of the draw, except that I got Colin’s name. He’s our driver and he’s ginormous. I might be exaggerating, but I reckon he’s 6 foot 12—and fancy-dress street caters for the kiddies.

In the end, I found the right mish-mash of ingredients— a generously-sized black cape, a golden party hat and a foam Sponge Bob. Now you might wonder why this was the perfect combo, until you remember that our truck is nicknamed Sponge Bob.

My challenge was to turn foamy Bob into wearable art. Luckily, I hoodwinked Colin into loaning me a shoelace, so I could turn Bob into ‘fashionable’ neckwear.

We resisted wearing our costumes as we crossed the border from Peru to Argentina, but we decked out for a trip through the shopping mall to buy groceries.

We donned them again when we went to town for a Halloween dinner at an Argentinian steak restaurant. We drew lots of stares, smiles, wolf whistles and laughs from all ages.

The next day we went back to behaving like grown-ups—sort of. Besides, our next party date was less than a week away—Guy Fawkes Day on 5 November.

P.S. Here are some pictures from the day. The four chickens are here. I came as the Giant Pumpkin.

In a rash moment, I said yes to tandem paragliding in Mendoza.

What was I thinking? Mendoza is Argentina’s leading wine-growing region and I could have signed up for any number of wine-tasting tours.

But I can drink wine all over the world, but paragliding in the Andes doesn’t come around very often. Besides the price, 400 pesos a person, couldn’t be beat. At our exchange rate that amounted to $60 for an hour of nail-biting fun and breathtaking scenery.

So eight of us took off with Mario and Diego of Paragliding Parapente for a new adventure.

And what a great day we had!

For each of us, the adventure began in an ancient Russian 4WD vehicle. Once loaded with two experts, two novices and all the gear, the little red beast made a 25–30 minute drive up a rugged Andean ridge to get to the ‘departure lounge’.

We heard in advance that the ridge was scary, and it was. Rocky and narrow, with drops that were close and sheer. After the ride up, everyone was more than delighted to be coming down on a glider.

Mario, who I think owns the company, is confidence inspiring. He’s been paragliding for 20-plus years and has more than 3000 hours in the air. From the outset, he explained that it was possible that not everyone would be able to glide. It all depended on the weather and winds.

It was also impressive to see the checks and double checks done as I got ‘suited up’. Nice to know that nothing is left to chance.

That said, the Mother Nature had her way when it came to take-off. Mario explained the procedure. Bend forward, legs straight, take four or so steps backward and then run forward.

I was hitched up to Diego (the Hunk) and before we even had a chance to think about making a proper exit, a gust of wind swept us into the air. Diego got in a few steps, but I was instantly airborne. I felt like Mary Poppins with a giant umbrella.

The ride down was amazing. Wonderful scenery—I could see all the way to Chile—viewed from 1750 metres. The mountain colours ranged from deep rust to charcoal to all shades of brown and green. I confess that I didn’t take my camera. I just wanted to enjoy the experience, without succumbing to my tendency to take too many pics.

Others did have cameras so stay tuned and I’ll do another post on the scenery.

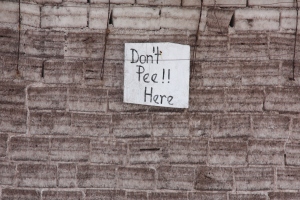

Every wall is a potential toilet, so warnings are common and often ignored. This sign is on the back wall of a hotel.

Even at its thinnest, perhaps especially at its thinnest, toilet paper is an unavoidable topic of conversation on an overland journey. Well, maybe not unavoidable, but certainly a matter of day-to-day concern.

Just yesterday there was a brief panic because our truck had RUN OUT of toilet paper. Now before any other overlanders faint dead-away from that comment, I have to assure you that this truck DOES NOT provide toilet paper. In fact, no overland company in its right mind would even fleetingly consider providing toilet paper.

Toilet paper is a personal thing. Quantities of toilet paper are a personal choice. I’m not going to confess how little toilet paper I can get by on, nor am I going to tattle on those who use two, three, four or even five times as much paper as I do to deal with a bit of wee.

So while an overland truck provides breakfast and dinner when passengers are camping (and sometimes lunch on long-drive days), it would never attempt to provide toilet paper for the masses.

This trip, our toilet paper supply actually comes from those masses. Early on, there was leftover money from some activity, and people used it to buy toilet paper—lots of toilet paper. Now it’s expected and a third purchase of the beloved paper was made today.

Poor John and I didn’t contribute to the first purchases—or if we did, we did so without realising—but we’ve happily anted up for the second two, for the bargain price of about 20 cents a person. There’s always a chance we’ll run out of our own supply.

And there’s the key—our own supply. In Africa and from London to Sydney, everyone had to buy their own TP (I feel I can use the abbreviation now that we’re on such familiar terms).

On those travels, the TP was often an industrial weight version in lurid hot pink, purple, blue or green. There were 20–50 sheets on a loosely-wound roll, and we went through it like mad even when we were being thrifty. When we stayed in hostel or hotels, most people would pinch a roll or two from their room or the shared toilets, but I would never take a roll—20 sheets, yes, but a whole roll, no.

Turkmenistan’s TP was a steely grey and like coarse sandpaper—my bum remembers it well and I saved a piece to show to disbelievers. I carry it in my camera case!

But the best TP was sold in Yaounde, the capital of Cameroon. Poor John found it in a supermarket near our campground. He bought a pack of four. What made it so good? It was soft, thick (at least 2-ply) and rolled super, super tightly—plus there was no inner core, just sheets and sheets of paper.

The packaging claimed each roll was equal to four normal rolls. But I reckon it was more like one to eight. And through economical use and occasional acquisitions from a hostel, we made it last for seven months—almost until the end of the trip.

I’ve brought two rolls on this trip, and we’re still on the first. We’ve stayed in so many hostels, it’s been easy to keep the supply topped up, 20 sheets at a time. I’ll let you know if I have to buy more before we get to Rio at the end of the year.

P.S. I’m going to do a piece on toilets too. Stay tuned.

Poor John is a whizz at researching the places we ought to visit wherever we go, so I tend to let him plan our itinerary on most of our sightseeing days.

Peru was no exception and the Larco Museum in Lima was high on his list, so we set out one morning by taxi. It was a longish and expensive (by Lima standards) ride via the suburb of Miraflores, but the driver was pleased that we were going to this amazing showplace.

Brought together by Rafael Larco Hoyle, the collection first went on display in 1926 in another part of the country.

Larco (although as a descendant of my own line of Hoyles in North America, I prefer the Hoyle tag, which was his mother’s) was passionate about archaeological research and preserving Peruvian artifacts from diverse cultures.

His enthusiasm was influenced by his father, who began acquiring northern Peruvian pre-Columbian pottery in 1903 when the young Larco was a toddler.

Like his father, young Larco bought collections—especially of pottery. But he also began extensive explorations and excavations in remote parts of Peru. Apparently, his family and friends entered into the chase and enjoyed taking part in fieldwork. So much so that today the museum has more than 40,000 complete pottery vessels and thousands of metal, textile, wood and other artifacts.

I was gobsmacked to see all of the Larco treasures. They are beautiful, diverse, well-displayed and awe-inspiring. The sheer volume of pottery and gold adornments is overwhelming. And the pieces cover at least six or seven different ancient cultures. It was a big bonus to be able to photograph the exhibits because the Larco Museum has fine examples of works that I couldn’t photograph in many other museums in Peru.

It was also a special treat to get a look inside the museum’s many storage rooms. These spaces hold countless, floor-to-ceiling glass cases of pottery pieces. Many depict the actual faces of men who were most likely sacrificed in ancient times. Each face is different, and all are beautiful and heartbreaking.

There’s also a large collection of erotic pottery, with some quite playful and many having sassy facial expressions. These displays no doubt contribute to the fact that the Larco Museum is one of Peru’s most visited tourist attractions. I took quite a few pics of the erotic specimens, but they’ll have to wait for the sealed section of the blog. 🙂

The museum structure and its beautiful gardens are worthy in their own right too. The exhibits are housed in an 18th century vice royal mansion that was built over a 7th century pre-Colombian pyramid.

Poor John and I decided to splash out on a meal in the deluxe restaurant there. He had grilled scallops (nine on a plate) and I had an exotic salad. Not cheap, but delicious, and I resisted taking photos of the meal itself.

Our drive from Chivay to Colca Canyon to see the condors included stops in several Peruvian villages.

There’s no doubt these villages are geared up for the morning tourist trade. We set out from Chivay about 6am and reached the first village, Yanque, not long afterwards.

Yanque was up and ready for our arrival with a group of schoolgirls (accompanied by several village dogs) in the main square doing a dance to celebrate—our arrival, I suppose.

The churches were open too and we visited ones in Yanque, Achoma and Maca.

In all the churches, it was interesting to see the statues of saints decked out in local dress, including hats typical to the region or the dominate culture. One female saint had four names embroidered on the skirt of her red gown—Rod, Charly, Samuel and Walter. I’m guessing either she or her gown was donated by them or in their memory.

The kiddies and their llamas were out in force too. Tourists, especially those with limited time in the country, find such villages are great places to have their pictures taken with a decorated llama and kitted out child. Luckily, we are in South America long enough to find other, less staged opportunities.

Every village had an army of souvenir sellers too. All the gear is pretty much the same—belts, bags, scarves, hats, gloves, knick knacks and soft toys—but the array colours always draws my interest.

The legitimate early risers were the farmers. They were out plowing. The countryside around Chivay and the Colca Canyon varies from flat to very hilly. It was interesting to see the mix of lush broad, flat fields and the heavily terraced hills that are planted to potatoes.

After running the gauntlet of villages—we arrived about 8:30am, along the thousands of others, to see the magnificent condors of Colca Canyon.

A couple of hours later, we went back to Chivay through all the same villages. The places were deserted and everyone had gone home. Obviously, tourist duty was over and it was back to normal life.

Today’s adventure is to the Bolivian salt flats near Uyuni. Old clothes are recommended. All my clothes are now old, so that should be no problem.

Not sure how much I’ll be posting over the next few days. We were in Potosi two nights ago. The hostel (in fact the whole town) had no electricity. I loved the fact that the anticipated outage was reported in the newspaper that came out AFTER the power went out.

In Uyuni, the hostel allows four people online at a time. Given that there are about 50 people staying here, a person’s turn comes around RARELY.

We head to Argentina first thing tomorrow morning, with a couple of nights of camping. I’ll be back as soon as I can.

Arequipa is Peru’s second largest city and in all our travels, it is the first place where we have been able to take a ‘Reality Tour’.

Almost everyone on our overland truck signed on for this interesting half-day tour that shows you aspects of a major city that are often ‘hidden’ from tourists.

Our itinerary started with a trip to the local market, followed by a visit to a wawawasi (child care centre for marginal families) and its attached comedor (where women cook hundreds of meals a day), and finally on to the sillar mine. These sites are in the shanty towns and/or outskirts of Arequipa.

Wherever we go, Poor John and I manage to visit most markets as we travel along, but we’re always looking forward to seeing a new one, and to seeing what new items might be on offer.

The Arequipa market had a couple of firsts for us. We saw the first pet stall—it wasn’t actually selling pets, but food, toys and other supplies. We’ve seen a lot of dogs in South America, but very few cats, and the products leaned towards dogs.

We saw stalls with up to 20 varieties of potatoes for sale. Usually we see no more than 10. Although thousands of types of potatoes are grown in Peru, most are reserved for home consumption. Oodles of varieties of cheese were on offer too.

We also saw the butchering and fish shops being run by women—again. I’ve found out why that is here, and will do a separate post on women butchers and fishmongers.

Our guide explained that the Arequipa market was designed by Mr Eiffel (of Eiffel Tower fame). It is large, bright and airy and, as usual, I took too many pictures.

Our main reason for visiting the market was to buy goodies for the child care centre and the sillar miners (our next two stops).

Pens, pencils, paper, puzzles and the like were on the list for the kiddies, along with fresh fruit. It’s a way to contribute to the centre and to thank them for sharing their space and time with us.

Preferred thank yous for the miners are bottles of water, bunches of bananas and bags of coca leaves (to chew for energy). Coca is popular throughout South America. And although it is the source for the production of cocaine, the leaf is invaluable at high altitude. Poor John and I chewed it several times a day as we did the Lares Trek.

But on to the centre where we met classes of engaging 3, 4 and 5-year-olds. It’s obvious they love having visitors. Each age group sand songs for us, and we reciprocated with tunes like the ‘Teensy-weensy spider’. The children are also learning English, and proved that they know more of our language than we do of theirs.

After spending time with the children, we walked along the compound and met the four women who make 700 meals every weekday. About 150 of these meals are served to people who come to the centre. The rest are delivered to families in need within a radius of about 5 kilometres.

Considering the output, the kitchen is tiny and the women who are cooking are about the same size as the pots.

Then it was on the sillar mine, which is open-cut and is supposedly 18 kilometres long.

Sillar is volcanic stone. It is extracted in a traditional way, and later used to build houses, fences and other structures. Most of Arequipa seems to be built of it.

We arrived around lunchtime and it took quite a while to find miners who had not yet knocked off for their midday meal.

The two we did find were most happy to demonstrate how the sillar is cut.

They start with a largish block that is then broken into smaller pieces with a hammer and chisel. The reduced pieces are halved and those halves are then trimmed to size with a mini sledgehammer. Apparently sillar is quite easy to work with at first, but it becomes harder as time passes.

Miners make about 200 blocks a fortnight and sell them for about $2 a piece. Each block weighs about 40-45 kilos.

The mine appears to be unsupervised and that anyone who wants to mine can do so, but we were pretty sure there must be some regulations that govern the extraction. That said, it was eerie when we arrived. There was no entrance and no gate. We just drove in. In addition to a lack of security, there wasn’t much in the way of occupational health and safety.

We were also surprised to see that the acres and acres of small chips of sillar go unused—they’re not even further broken down for gravel.

The outing was fascinating in every way, and I hope more cities think of adding reality tours. We need to get out of our comfort zones.