Never enough gold furniture

In a matter of a few weeks, we’ve gone from hot, dry West Africa to hot, wet Vietnam. We arrived two days ago.

Our daughter, Petra, who lives in Ho Chi Minh City, told us not to join the ‘landing visa’ queue on arrival. ‘You already have electronic visas, so go straight to immigration.’

Unfortunately, the guy at immigration thought otherwise. He ignored our e-visas and sent us, along with many others, back to the queue for visas on landing.

Two hours and US$50 later we managed to collect our luggage—two bags sitting on their own next to carousel 2. The fact that the cashier for visas managed to disappear for long periods of time added to the delay. Luckily the airport had wi-fi, so I was able to let Petra know about the hold up. And Poor John reminded me it wasn’t as bad as the last time we entered Vietnam when we were stuck overnight at the border.

Anyway, Petra was puzzled and annoyed by this change of system. It had worked perfectly well for others in the past. She discussed the matter with her work colleagues and speculated that it was because immigration hadn’t reached its financial quota in July.

Nope, her colleagues were confident that it was because ghost month had begun and ‘it’s bad luck not to pay your fees because the spirits of your ancestors will get you’. Below I’ve added a short explanation about the annual Ghost Festival observed in much of South East Asia.

After leaving the airport long after dark, we were pleased to find one of the two taxi companies Petra had recommended. She said the ride would take about 30 minutes and the fare should be about 140,000 dong (or less than A$10). One guy pretended to be from a recommended company, but his offer of a $25 fare exposed him as a fake.

Our taxi got us to Petra’s place for 139,000 dong. I managed to take a couple of pics along the way, including one of a furniture showroom/workshop where two fellows were adding gold paint to chairs.

Yesterday was a chance to settle in. We explored the nearby markets and treated ourselves to pho (the famous Vietnamese noodle soup) and a watermelon juice (less than A$5 each).

We’re in the Mekong Delta now and it’s pouring with rain.

Ghost Festival

The Ghost Festival is held during the seventh month of the Chinese calendar. It also falls at the same time as a full moon. During this month, it is believed that the gates of hell are opened and ghosts are free to roam the earth where they seek food and entertainment. These ghosts are believed to be ancestors of those who forgot to pay tribute to them after they died, or those who were never given a proper ritual send-off.

In Vietnam, this festival is known as Tết Trung Nguyên. It is a time to pardon the condemned souls who have been released from hell. The ‘homeless’ should be ‘fed’ and appeased with offerings of food and, presumably, the extra $50 for visas we already had.

Pho and watermelon juice

Let’s be honest—life in Africa can be tough, really tough.

In the course of our travels, I’ve met people who don’t have jobs but who want to work. Others have been employed, but don’t have enough money to send a brother or sister to school. Some find it hard to look after a parent who is blind or unwell. And way too many are generally unwell.

There are people who have lost family members to AIDS or horrific road accidents. We came down a mountain road to find an overturned/crushed ute (pickup) that had been fully loaded with passengers. It had toppled over a missed curve. Hard to believe that anyone survived.

Yet, in the face of all this hardship and heartache, Africans still manage to smile.

So this post is about the many smiles we saw this year. As I go back through photos, I’ll probably find more, but these are here to brighten your day.

P.S. We are back in Australia now, but heading to Vietnam later this week to visit Petra, the daughter who lives there on a diplomatic posting. You can expect a mishmash of postings that cover Africa, Vietnam and everything in between.

In the comments on my last post, fellow blogger Sharon Bonin-Pratt asked what we ate most of the time on this most recent African trip.

Overland travel and camping in Africa means we were almost always shopping in local markets (proper supermarkets are rare outside the big cities in West Africa).

Generally, the markets have tinned goods and fresh items that are in season and abundant. In all our African travels—now and 10 years ago—the most widely available fresh ingredients have been tomatoes, onions and eggs, eggs and more eggs.

You don’t want to know how many eggs I’ve eaten over the three months of this trip. Oh okay, I’ll confess. We usually bought eggs in trays of 30 and usually bought two trays a day—for just over 20 people.

Nassian was an exception—they didn’t have any eggs. This village was our first food shop in the Ivory Coast. Luckily it wasn’t my group’s turn to shop and cook, so I was free to tag along and take photographs. Frankly, I love markets and could bore you with pics of every market I’ve ever visited.

The Nassian market was quite basic, but still sold an array of food, clothes, tools, toiletries, fabric, towels, fans, luggage and more. Potatoes were on sale, which was rare at this time of year. Two local fellows even bought a live goat.

Carrying a goat

Goats to market

I was delighted to see an Orange phone shop across the road from the market. I bought one of their SIM cards in Bondoukou when we first entered the country, but I ran out of time to get in activated—too many people in the queue in front of me. So after photographing the Nassian market, I made a beeline to the fellow sitting out the front.

He didn’t understand any of my French or even any of my charades trying to explain what I needed. Turned out he didn’t work there and was just sitting in the shade of the large umbrella. I suppose he spoke the local language, but not French. As it turned out, I never managed to activate the SIM for the Ivory Coast.

Most of the pics don’t have captions, but you’ll see what’s going on.

P.S. Do you ever have the good fortune to shop in a local/farmer’s market?

Weighing potatoes

Elephants in 2009

Elephant 2019

Elephants gather at the edge of a main watering hole, 2019

Africa is famous for its wildlife, especially the big five—lions, elephants, leopards, cape buffaloes and rhinos. But the big five are most common in the south of the continent. We saw all of them there when we travelled overland through Africa back in 2009.

This year we travelled up north, in West Africa only. It’s that bit of Africa that bulges out on the left side. There aren’t quite so many animals up there, but there are more than enough to satisfy wildlife lovers.

Kob antelope (the West-African subspecies Buffon’s Kob) 2009

In 2009 and again this year, we visited Mole National Park, Ghana’s largest wildlife refuge. Mole (pronounced Mo-lay) is home to 93 species of mammal, including elephants, hippos, buffalos and warthogs. It’s an important preserve for African antelopes, such as kobs, waterbucks, bushbucks, oribis, roans, hartebeests and two kinds of duiker.

The park is also popular with primates. There are black-and-white colobus monkeys, green vervets, patas monkeys and olive baboons (also called Anubis baboons).

On both visits, we saw plenty of baboons and made a point of steering clear of them. They are aggressive, hungry and thieves. While the park has motel-type accommodation and a restaurant, we chose to camp. That meant we shared the area with hungry, opportunistic baboons. You can’t leave food or even a tube of toothpaste in your tent because they’ll break in and take it.

Back in 2009, a baboon came in through the skylight of the van we were riding in. He was after a chocolate bar one of our companions was holding. The driver beat him off with a club that he carries for just that purpose.

Baboons in the campground waiting to steal something (2019)

A field of baboons, 2009

Beyond mammals, Mole has 33 species of reptiles and 334 species of birds. Sadly my telephoto lens conked out early in the trip, so the birds in my pictures are the size of a flea.

You’d think seeing all the wildlife and landscapes would be enough, but there were two unexpected events at Mole.

Gary being interviewed by Ghana TV. Elephants in the water in the background (2019)

First, a TV crew turned up at the park (mostly because of the second unexpected event). Gary, who we have been lucky enough to travel with repeatedly in Africa, India, and London to Sydney, was interviewed about his experiences in Ghana. Turns out he was interviewed for TV on a previous visit to the country. He must be a media magnet.

Second was meeting the 2018 Miss Ghana Tourism Ambassador and her two princesses. Apparently these three women are travelling the country to promote the most popular destinations. Elorm Ntemm is the ambassador. The two princesses are Maud Kunorvi (1st) and Ama Owusuaa (2nd).

The 2019 Miss Ghana Tourism Ambassador will be crowned in August.

Elorm Ntemm (centre), 2018 Miss Ghana Ambassador, and princesses, Maud Kunorvi (left) and Ama Owusuaa (right)

A bit more about Mole

Mole dates back to 1958. That was when land was set aside for a wildlife refuge. In 1971, the small human population was relocated from the area, and the land was designated as a national park.

The park is poorly funded to prevent poaching, but professional and armed rangers guard the animals.

The Mole and Lovi rivers flow through the park during and after the rainy season. The park gets about 1000ml (40 inches) of rain a year between April and mid-October.

An armed ranger on duty in Mole, 2009

The park in 2009

About the pics here

This post includes pics from 2009 and 2019. Ten years ago, we visited in the month of May. That was after the rainy season had begun, although I don’t remember it raining while we were there. This year, we visited in March, at the very end of the dry season. You can probably immediately figure out what year a pic was taken, but I have added dates for your convenience.

Ants on the march, 2009

Elephants enjoying a bath, 2009

Korhogo was one of those overland stops with a bit of everything. We saw cloth being woven and decorated, granite being chipped, bead making, wood being carved, a typical village, and some amazing traditional dancing.

We’d been told that the dances were quite athletic, but you can never be exactly sure what that means. Turns out the star attraction is the Boloye, or the Dance of the Panther. The name stems from the fact that dancers wear costumes that are reminiscent of panther fur. And the dance is definitely energetic.

An airborne dancer

Airborne again

Historically, the Boloye was a sacred dance of the Sénoufo (Senufo) community in the Ivory Coast. It used to be performed only at funerals and possibly at initiation rites, but now it’s more widely shown. It must be highly regarded because photos of this type of dance were featured on tourist posters throughout the region.

We saw the dance performed in the village of Waraniéné.

The event started with an ad hoc dance by children. It went on for about 15 minutes with the assembled band providing music. Eventually, some of these kids will be part of the main attraction, but that day they were improvising. It was great fun to see their moves.

One thing you might notice from the pics of the kids dancing is that people carry babies on their backs. We saw that all over Africa—this time and 10 years ago. Women, children and sometimes men wrap a cloth around their waists to hold their babies securely on their backs. It’s a fantastic way to do hands-free carrying. I’m surprised it has never caught on in the West.

But back to the main performance.

The all-male band had about 15 members. That said, a few other men wore the same blue and white shirts and black and white beanies as the band members, but seemed to have more of a managerial role.

I’m pretty sure the instruments were the shekere, a gourd covered in netting and wooden beads, and a larger drum, that looks a bit like a kora but doesn’t appear to have 21 strings. I haven’t been able to find a name for the latter instrument.

Our guide shows us a shekere up close

The band plays and sings

I’m guessing that most of the costumes were made of cotton, and you can see that they were dyed in earthy colours, as well as black. Their ankles were decorated with grass or wool (not sure which) and they had twigs for hands.

There were nine masked dancers, presumably all male. I believe the small one was a child. They entered single file and did an introductory routine (shown in the first video). You can see how they greet/acknowledge each of the band members, as well as the audience in general. You’ll see one dancer shoo a couple of children away from the ‘dance floor’.

The youngest performer

The most elaborate costume

All the dancers then sat on the ground off to the left and performed one by one. In the last video, you can see how they greet/acknowledge their fellow dancers before each performance. You’ll also see just how athletic these guys are.

Each dancer did at least three routines and while some were more complicated and athletic than others, they were all excellent and well timed. I was especially impressed by how well the dances and music complemented one another. Clearly these are routines that are well rehearsed.

Our guide demonstrates a musical instrument

Whenever Poor John and I arrive in a new town, we seek out a local museum. Sometimes there’s more than one. Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, has two important museums—one featuring national culture and the other featuring the history of trains in the country (more about that in another post).

Inspiration for the national museum began in 1953. At that time, Governor Sir Robert Hall encouraged the formation of the Sierra Leone Society. He then challenged its members—mainly colonial expatriates and the Creole elite of the city—to establish what later became the national museum.

The magnificent Cotton Tree

We found it easy enough to find the National Museum. It’s in the old Cotton Tree Telephone Exchange in the centre of the city, and has been there since its opening in 1957. It was supposed to be a temporary location, but it’s still there. The telephone exchange was named after a large cotton (kapok) tree that is still nearby.

The museum isn’t overflowing with exhibits. Sierra Leone has suffered considerable conflict over the last decades, but in recent times a Reanimating Cultural Heritage project has digitised more than 2000 museum objects and documented traditions and raised awareness of their significance.

One of those was the photo of Bai Bureh. In 2013, the museum displayed the only know photograph of this Temne guerrilla leader, who started a war against British rule. I wrote about him here.

Two of the museum’s most comprehensive exhibits feature tribal masks and ceremonial costumes.

According to a placard in the museum, the distinctive helmet-style masks are worn by members of the Ndoli Jowei, the ‘Dancing Sowei’, an exclusively female Sande or Bondo initiation society. Traditionally a senior member of the society wears the mask and a black raffia costume, which disguises the wearer’s identity, during the annual initiation of girls. Today a Ndoli Jowei appears (and dances) at a wide range of social events. It is thought to be the only masquerade figure that is actually performed by women anywhere in Africa.

A classic Ndoli Jowei mask is made of lightweight wood and dyed black. It has an elaborate hairstyle, small face, delicate features, pursed lips, downcast eyes and scarification marks on the cheeks or near the eyes.

While a lot is probably known about the ceremonial costumes, but I’ll be darned if I could find any placards that explained them. Our guide didn’t know much either.

But the photos show the construction. The materials are diverse and great fun. There are shells from small to large, dusters, brooms, grasses, horns, teeth, toothpicks, cloth, fishnets, gourds and more.

One particularly elaborate costume has what I think is a stylised ram’s head. It’s heavily adorned with hundreds of shells and long grasses, as well as two dusters for hands. I had to laugh when I saw the timber toothpick holders, complete with toothpicks. I used to own one of those. Another featured a crocodile head and numerous large shells.

I can’t imagine how many hours it took to construct these garments, and I wish I knew who wore them and under what circumstances. Some of the displays had a name at the base, but even searching online hasn’t explained much.

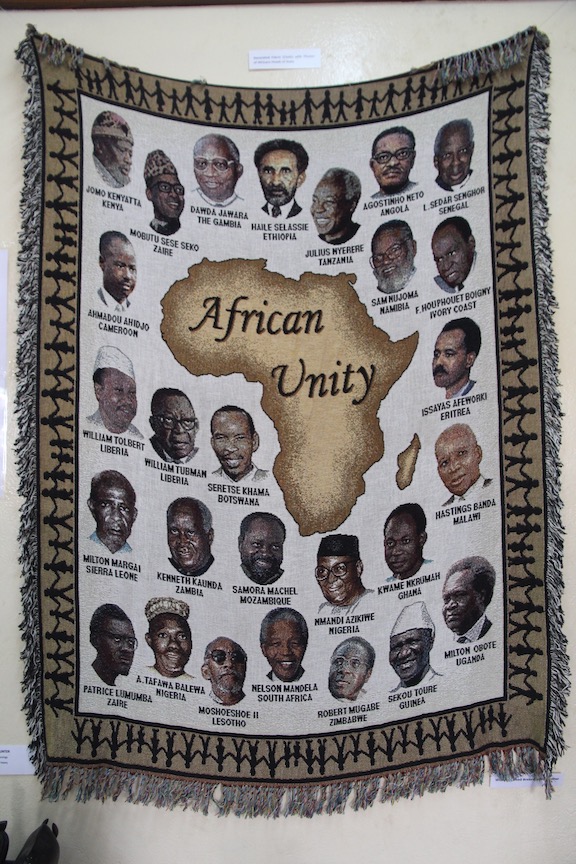

There are loads of other interesting items—household goods, work tools, musical instruments, games and charms. There’s a map of the continent of Africa carved, sadly, on a tortoise shell and a banner showing African leaders from the days of Nelson Mandela.

Work tools

Banner of African leaders

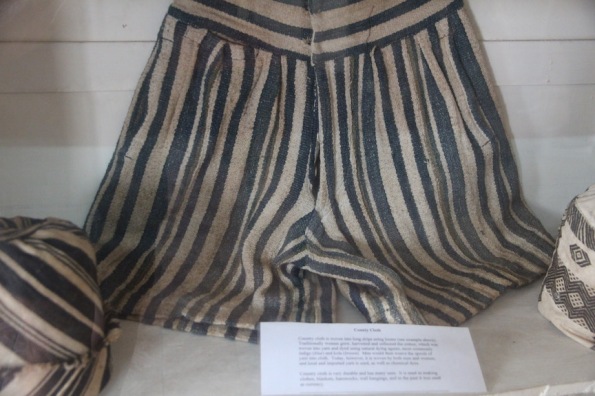

I have a weakness for fabric—I bought more than 10 metres of fabric on this trip—so was interested in what’s called ‘country cloth’. Traditionally women grew, harvested and dyed the cotton (usually in blue or brown), while men wove the cloth. Today it’s done by both.

The cloth is woven in long strips. It’s durable and is used to make clothes, hammocks, blankets, wall hangings, and, in the past, as currency.

Country cloth shorts

Country cloth

Poor John is second from the left

Regular followers of this blog will know that Poor John almost always walks with his hands clasped behind his back. It’s his signature pose. I’ve written about it here and here.

People who have travelled with us in the past get a kick out of sending me (not him) photos of other people doing the same. They also like to copy his pace.

This African trip was no exception. Most of the truck group went out to dinner one night in Yamoussoukro, capital of the Ivory Coast. I think Poor John was completely unaware of his following.

I wonder if any of them are keeping up the tradition? I wonder if any of you walk this way? I do sometimes.

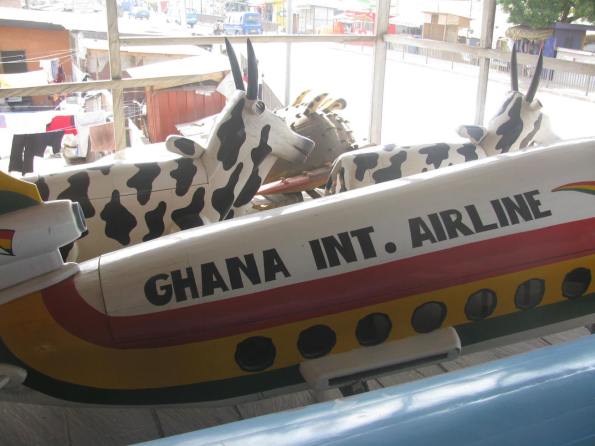

An airplane coffin in 2009 (cows in the background)

An airplane coffin in progress in 2019

One of the first posts I wrote regarding our travels this year in Africa was about a meal we had in the Ghanaian town of Teshie.

But food is not the main reason a person heads to Teshie. Nope. It’s the elaborately carved and hand-painted coffins that draw people from all over Ghana, in fact from all over the world, to this town. Some want to buy these ‘fantasy’ coffins and others just want to see them.

Back in 2009, we made a special trip to Teshie just to visit the workshops. But once is never enough for a place like this, so three of us (Poor John, me and fellow traveller, Dee) grabbed a taxi and headed east from Accra.

Coffin showroom from the street, 2009

Entrance to coffin showroom

It was amazing to discover how little some things change. The main workshop is in the same place and looks much the same as it did 10 years ago. Just like in 2009, we were told it was okay to go round the back and up the stairs to the showroom, so off we went. I was surprised to see a child-size fish coffin that had been there on our first visit. Maybe it’s a new one but, judging from the weathering, I reckon it’s been kept for display. Each coffin is made to order.

The custom seems to have started sometime between the mid-1940s and the mid-1950s, and reflects a local attitude to the afterlife. The Ga people, an ethic group in Ghana and Togo, believe death is not the end and that life continues in the next world in the same way it did on earth. So the right send-off is important. (As an aside, West Africans spend a fortune on funerals. I saw banks with signs offering loans for homes, cars, education and funerals.)

The Western world was first introduced to these masterpieces at an exhibit in 1989 in Paris at the National Museum of Modern Art (Musée National d’Art Moderne).

A coffin usually depicts the deceased person’s profession, hobby or passion. Sometimes it indicates their status in the community.

In addition to the little fish we saw back in 2009, we saw an airplane for a pilot, a cow for a farmer, a pencil for a teacher and many more. This time we saw a flour bag, a vegetable, a camera, a truck, a spider and an eagle. Some were complete, some were in progress and some were ancient.

There was also a gorilla’s hand, but this wasn’t a coffin. It was a ‘throne’ made for a village chief. If I understood correctly, the chief was carried in it for a parade.

By the way, we saw a few more coffin-making shops on the side of the road as we drove through West Africa. Not sure which country, but I’ll try to let you know.

A throne for a village chief

Looms are hand and foot operated

Women decorating Korhogo cloth

Back in early March, we were in Korhogo in the Ivory Coast (Cote d’Ivoire) in West Africa.

We figure there’s no sense going to these far flung places if we don’t have a good look around, so we took advantage of a full day of guided visits to several touristic destinations. I’ve already written about the bead-making and granite chipping sites, but today I wanted to tell you about two fabric sites.

Frankly, I have a weakness for cloth and textiles in general. It is the souvenir I am most likely to bring home with me—that or some cooking gadget—and these two sites were especially appealing.

I hadn’t realised that Korhogo cloth is world famous. It’s up there with bogolafini (mud cloth) from Mali and Kente cloth from Ghana. I own some of both from previous travels in West Africa.

Korhogo cloth got going in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Back then, American Peace Corps volunteers encouraged the Senufo people to explore new styles of clothing production. They already made fila cloth and that provided inspiration for Korhogo cloth.

The cloth is made of hand woven and hand spun cotton. Men and women cultivate the cotton (we saw huge piles of cotton as we travelled through the country). Women spin it into yarn and prepare the dyes, while men weave and decorate the fabric. The looms are foot operated. We also saw women embroidering pieces of clothing.

Some finished cloth is made into garments and household accessories, such as bedspreads and tablecloths. Other pieces are turned into artworks. The paintings are done using specially fermented mud and plant-based pigments that darkens over time.

Our first stop was at a place that abounded with cotton, looms and men weaving fabric. Around the perimeter there were women adding embroidery to works already completed. Lots and lots of clothing or household items were on display. In fact, even the trees were festooned with fabric. Of course I bought something…er, somethings.

Later in the day, we visited another site where people were painting or embellishing cloth. For example, one fellow was splattering paint (or mud) on pants. Two fellows were adding designs to rectangles of fabric.

Designs usually depict human forms or animals that are important in Senufo culture and mythology. I resisted buying anything at this stop. Although looking at the pics , I am now suffering from regret.

I couldn’t resist sharing a lot of pics (not all have captions). Too much gorgeousness to look at.

Splattering paint or mud on Korhogo pants

Korhogo cloth in the mud cloth style

Have a look

It hasn’t been easy to follow and comment on other blogs while we’ve been travelling, but every now and then I have a decent internet connection, and I check out as much as I can. I laughed myself silly when I read Ortensia’s post about taking her dog to the vet. As one of the commenters said it ‘was like a scene from a comedy film’. Check it out if you need a good laugh.

I got the impression that the young fellow on the left was an apprentice

He gets a turn to paint

Laundry draped on rocks

Laundry hung between buildings and draped on bushes

I love getting comments on my blog and a recent one (by Susan over at onesmallwalk)

Great market, such colorful displays. But it was the laundry in the breeze

that makes me want to visit—Susan.

has prompted me to do a post devoted to laundry in Africa.

Frankly, I love seeing laundry being dried around the world. The colours, the fabrics, the breezes, the ingenuity.

Hotel bedding spread on the ground and on a line

Laundry draped on a fence

The ingenuity? There’s plenty of ingenuity. It’s important to remember that not everyone in the world has a clothesline or a clothes dryer. In fact, not everyone can afford clothespins (pegs in Australia). So getting clothes washed and dried requires a certain amount of creativity.

We understand that. On camping trips—heck on almost all of our trips—we carry a bag with laundry soap, clothesline, pegs and a universal plug. It’s usually quite easy to find a sink but not always easy to find a plug. Trust me, a wadded up sock doesn’t keep water from oozing quickly down a drain.

Interesting to note that Liberia was the first time we saw clothespins (pegs) being widely used. The photos here are from several West African countries.

Laundry on bamboo poles and clotheslines

Laundry on bamboo poles

So here is a collection of pics that show how West Africans get clothes dried.

The rooftop and balcony pics at the bottom show clothes that belong to us and other people on our truck. I found these drying spaces quite by chance. Some of us camped in tents and others opted for cheap rooms. Most of us put in laundry—nice to have a break from doing your own washing.

Laundry drying outside a shop

We were told that the upstairs was unfinished. They said the rooms weren’t complete or furnished. The snoop in me thought I’d go up and have look. The rooms were as described and the laundry was in full sight.

As an aside, I’ve written many posts about laundry and there will be more to come. Here’s one from Burkino Faso and another from India.

So how do you get your laundry dry?

That’s my pale green shirt in the foreground

Plenty of clothes fit on a rooftop