A group of friends/colleagues pose at the sacred tree

A six-in-one tree

Regular readers of this blog will know how much I love going to markets. So I was delighted when our stay at The Little Boabab in Abéné included a village walk. It would give us a chance to explore the local craft and food markets, and to visit the community’s amazing sacred tree.

We set out early in the morning with our guide, Saikou. Saikou is from The Gambia, but he has lived and worked in the Casamance (southern) region of Senegal for about five years. His English is great (The Gambia is English-speaking) and he knows Abéné well.

Welcome to craft market

Market welcome with the sacred tree

Beaded statue

Our first stop was the craft market. Because we arrived quite early in the morning only a few shops were open, but it was great to see the range of carvings, including plenty of masks. I’m not all that keen on masks. I love seeing them used in dance performances and other ceremonies, but I don’t need to see them hanging on my walls. Not sure where that attitude has come from.

The actual food market was next. It was a special treat to visit with Saikou because he let us know that photos would be okay. This was a welcome change. The further north we have travelled in West Africa, the less likely people have been to be pleased to have their photos taken. You can’t imagine how many photos have been captured in my mind’s eye, but not on camera. Darn.

The final stop was at Abéné’s Bantam Wora, or sacred tree. It’s actually six huge kapok or cotton (fromager) trees that have fused together.

People in the Casamance believe fromagers are sacred. They are thought to be possessed by a genie that can bring good fortune if offered kola nuts, biscuits, milk, bread or other delicacies. For example, women with fertility problems or young men wishing to win an upcoming football match will go and make an offering.

Before arriving, we were told that we would have to make a financial offering to the women who spend their days around the tree. We dithered about that at first. Senegal has huge paper money notes, and none of us really knew how to contribute. Luckily Adam, one of our drivers, was with us and offered a blanket donation.

The tree is ginormous. It could easily be six, eight or 10 trees fused together. A youth group (maybe university students) was there when we arrived. A group shot of them shows just how large the base of the tree is.

Taga (left) and Saikou

The colourful bar at The Little Boabab

The Little Boabab is the most heartwarming and welcoming place we’ve visited in West Africa. It also has a huge touch of sadness (read on). Nestled in the village of Abéné in the Casamance (southern) part of Sénégal, The Little Boabab is the love child of Simon and Khady.

Years ago, Simon Fenton, an English journalist, fell in love with West Africa and Khady, a Sénégalese woman, who spoke only faltering English back then. Together they realised a dream and started to build The Little Boabab.

Sadly, I wasn’t lucky enough to meet Simon. About 18 months ago, he was killed in a car accident when travelling between Abéné to Ziguinchor. The mere thought of it breaks my heart. My own father was killed in a car accident when I was 18. You can read about him here.

When we arrived at The Little Boabab and met Khady, I gave her a huge hug and said that I ‘sort of’ understood the grief she was going through. I lived through the loss of a father, but how could I possibly understand the loss of a husband, and especially in her circumstances? She has two gorgeous and energetic young boys—Gulliver and Alfie.

Gulliver (left) and Alfie are ready for school

We stayed two nights at The Little Boabab. We enjoyed delicious meals, a comfy bed with mosquito net, a guided village walk and an incredible dance performance. It’s also where the dancers managed to get Poor John on his feet.

Little Boabab is a full-service, solar-powered campground. They provided all meals, and I was lucky enough to barge my way into the kitchen to help on our second night. I learned how to stuff bone-in chicken thighs and drumsticks.

Helping in the kitchen at The Little Boabab

Expect more posts about Little Boabab and surrounds.

Simon wrote about his experiences. You can buy his books Squirting milk at chameleons: an accidental African and Chasing hornbills: up to my neck in Africa here. I was lucky enough to buy mine at The Little Boabab.

Poor John living it up at The Little Boabab. He looks like he is having fun

Richard crosses the bridge

Stephan climbs to the bridge entrance. There’s a similar entrance on each end

West Africa is a land of amazing contrasts! Bridges are a good example. You may remember that we ‘fell’ through a log bridge a few weeks back. That was a first for our co-drivers, Jason and Adam, as well as for all the passengers. We’ve also crossed plenty of modern concrete bridges—no risk of falling through those. And on occasion, we’ve detoured through a stream (it is the dry season) rather than cross a bridge that is being constructed or repaired.

One person crossing at a time

But we visited a very rustic bridge not far from Nzérékoré, in southeastern Guinea. It was made entirely of vines and bamboo. It was fascinating to see its construction up close, and to have the chance to cross on foot—one at a time.

The bridge is brilliantly sturdy and I’m sure it could carry more people at once, but we respected the villagers’ instructions. Our guide—the bridge is in a forest and was about a 45-minute walk from where we parked the truck—said the bridge is as old as anyone can remember. I’ve read accounts that say it was built more than 100 years ago.

In addition to providing safe passage across a river, the bridge has spiritual significance for the people. Two years back, it was closed for renovations and repairs. That year the overlanders weren’t even allowed to approach the bridge. I heard differing comments about why. Some say that repair work is done by spirits, while others say it is done by trusted elders who don’t want the secrets of construction shared. Keep in mind that my French is fairly sketchy, so the ‘real’ story could be something entirely different.

Word gets out when foreigners are around. By the time we got back to the truck there were several people selling avocados and other fruits. I bought 10 large avocados for about $3. They were nicer than any we’d seen in the markets. Too often the fruit we buy turns to mush within a day or two. These weren’t ripe yet and several cook groups managed to use them over the coming days.

I also got a fun pic of a woman’s toes. She’d painted them along the lines of the Guinean flag. Fashion in the forest!

Avocados for sale

Ellen is dwarfed by the sheer size of the bridge

A typical African windscreen (windshield)

Poor John gets in the front

Not long ago in Nzérékoré, Guinea, West Africa, I was reminded of a lift we were given in Barnaul in the Altai district of Russia. Five years ago, Elena and her husband kindly offered to give us a ride to a bank so we could change Kazakh money to Russian roubles.

She explained in English that they had just come from the police station where they had been completing paperwork. She went on to say ‘Go ahead, get in the car. If you aren’t afraid!’

That phrase ‘if you aren’t afraid’ pops into my mind every time I get into an African taxi. Yesterday we rode in three taxis in Dakar, Sénégal. All three had cracked windscreens (windshields), at least one door that didn’t open from the outside or inside (scoot across), windows that didn’t open, and two of three drivers who had no idea where they were going.

Petrol cap and door missing

Back end of a station wagon taxi

The first driver couldn’t read and didn’t speak English or French, only Wolof (the local language). We didn’t realise all that until we reached our destination and even the fellow at the hotel (who spoke four languages) couldn’t communicate with him. He had to run up the road to find someone else who spoke Wolof.

But the most memorable taxi ride of this trip so far has been the one in Nzérékoré. Dee, Ellen, Poor John and I wanted to go to the large artisan complex on the edge of town. Of course, the taxi driver had no idea where it was, but we had a scribbled map. Hahaha

As with every African taxi I’ve ever ridden in, the windscreen was cracked. But there’s more.

Ellen scoots across and avoids the hole in floor

Doors worked on only one side of the car and had to be yanked open, there was a large hole in the back seat floor, the petrol door and cap were missing, The back end and car ceiling had lost their fabric coverings, and the taxi had to be pushed to get started.

Of course, we weren’t afraid, but we laughed ourselves silly and all got in. The driver made the mistake of turning off the engine when he dropped us off (yes we found the complex), and had to be pushed again to get started. The taxi home was about the same, but didn’t need to be pushed.

Getting a push after we get out

We found the artisan complex

Freetown, Sierra Leone—apartment building or house?

On the outskirts of Freetown, Sierra Leone

My last post focused on the simple thatched huts of West Africa, but I don’t want you to think that is the only housing available.

Thatched huts are common in villages, but towns, cities and even larger villages have all sorts of more modern and elaborate homes. Some are really over the top, with fabulous paint combinations or tiled exteriors. Poor John reckons the tile is to minimise mould in the rainy season. Makes sense to me.

House with shop to the left

Some of the homes shown are built over shopfronts or other businesses. Others are apartment buildings.

I thought you’d like to see a variety of the accommodation I snapped from the truck window. We’ve seen a few presidential palaces, but photos weren’t allowed.

P.S. Not many captions.

Shops below

Old-fashioned house in Sierra Leone

Tiled exterior in Labé, Guinea

Bundles of grass in front and to the side of four huts

The roof is framed and the grass bundles are on the right

Overland travel gives us a great chance to observe daily life in towns, villages and the countryside.

As we’ve moved from country to country in West Africa, one of the most noticeable differences is the style of housing and construction. Some differences are slight while others are more varied. Northern Guinea and Guinea-Bissau were the first places where I saw simple roofs being repaired for the rainy season. Maybe this is now happening in all the countries we’ve already visited.

When I first saw the bundles of grass in the two Guineas, I assumed they might be feed for animals, but it didn’t take long to realise this was roofing material for buildings covered in thatch. I don’t know how much the grass costs or how much it takes to cover a roof.

Grass for roofs

Roofing materials stored off the ground and a style of fencing I hadn’t seen before

I thought you might enjoy seeing the various stages in the process.

As an aside, we took a two-hour boat trip through extensive mangroves in The Gambia. Our guide, Omar, is rushing to get his house built (or at least enclosed) before the rains begin in June. He is using corrugated iron for the roof. He needs 10 packets of the stuff—I don’t know how big a packet is—at 1800 Gambian dalasis per packet. That’s equal to about 330 euros for all 10 packets. So far, he’s purchased four packets of new roofing material and hopes to find cheaper secondhand materials for the rest. We tipped him generously.

Roof in progress

Finished roof

Just a quick post before we hit the road again. I don’t have many shots like this because we’re travelling at a speed that means my pics are out of focus.

Here are a couple to show you how many people (and their stuff) can fit in/on a single car. No captions needed.

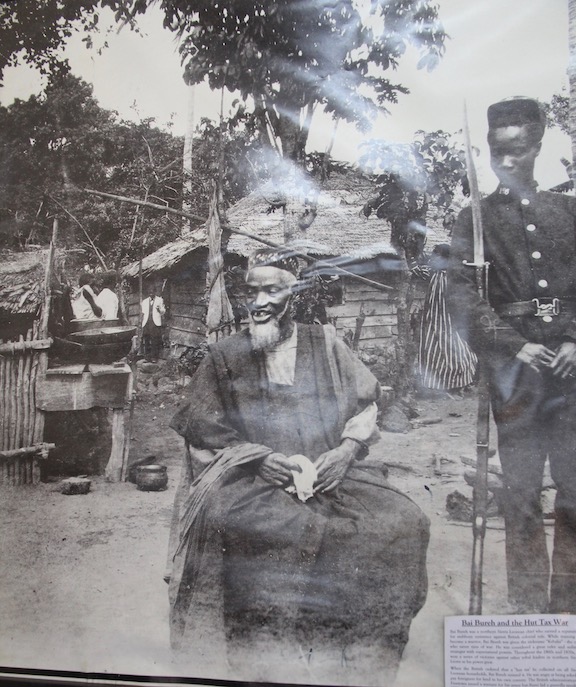

Bai Bureh, the Hut Tax rebel

We learned the story of Bai Bureh at Sierra Leone’s National Museum in Freetown. As a chief in the northern part of the country, he earned a reputation for stubborn resistance against British colonial rule. It’s not surprising.

When he trained as a warrior, Bai Bureh was given the nickname Kebalai—one who never tires of war. He was considered a great ruler and military strategist with supernatural powers. Throughout the 1860s and 70s, he won many battles against neighbouring tribal leaders.

Perhaps this drum was used as a call to arms

His biggest fight began when the British ordered that a ‘hut tax’ be collected from every Sierra Leonean household. Bai Bureh was furious that a foreigner asked him to pay tax on his land in his own country. His refusal to pay caused the British to issue a warrant for his arrest. In 1898, Bai Bureh led a guerrilla revolt that became known at the Hut Tax War. Although his men held the advantage for some time, Bai Bureh was eventually captured and sent into exile. He returned in 1905 and reinstated himself as chief of Kasseh.

You have to love his style and attitude.

P.S. All pics were taken in Sierra Leone’s National Museum in Freetown. The main pic features Bai Bureh. The other two are of his possessions or those of his followers. Stay tuned for a post on more museum items.

I think these were weapons

Paying our respects to the chief and his wife (outside his house)

The chief poses with his mother

Africa’s big cities can be as cosmopolitan, crowded and commercial as those in other parts of the world, but many of her villages are set in another time.

Over the last two months, we’ve travelled more than 6000 kilometres through six West African countries. In addition to staying in a few hotels and hostels, we’ve camped in the middle of nowhere, in school grounds, in hotel gardens and in villages.

Villages are certainly the most fun and most educational. This is because we get to interact with people and have a close-up look at their lives. That means peeking inside houses, sampling local dishes and learning smatterings of a local language.

It’s not unusual to meet people who speak three or four languages—in West Africa that’s English and/or French plus one or two native languages. Later I’ll introduce you to Hassan who speaks six languages.

But today is a trip to Byama (spelling?) in rural Sierra Leone. It’s about 2 miles from Kambama, the village we stayed in after the truck fell through the bridge.

Mohamed, our host in Kambama, walked a group of us to Byama and introduced us around town. Our first task was to visit the village chief and pay our respects. That’s what you do whenever you enter a small village.

We met him, his pregnant wife, his mother and some extended family. We also met the school principal and his two wives (yes two). The school is in Kambama, but the principal and teachers live in Byama.

Then we were guided through the village and encouraged to take pictures. Byama and Kambama do not have electricity or running water. Both do have village wells that are pump-it-yourself operations.

As in most villages, we were swarmed by children at every step. They love to stroke your skin, feel your hair, shake hands, clap, have their pictures taken and try out some English words.

It’s good to be reminded that we are the unusual ones and that we have been welcomed into their realm as guests and not as intruders.

Our visit to Byama was one of the activities offered by Kambama village, and we each paid about $5 for the excursion. The next day, a few of us did a similar stroll through Kambama. Interesting how villages are the same, but different.

Children looking at pics of themselves

Laundry undercover in case of rain

The school principal shows off some plant cultivation

Kitchens are simple affairs in Byama

Schedule of fees. Ten thousand francs (10,000) is worth about 1 euro

Many of you have asked after Jason and his health. After a night on a drip in a rural hospital and plenty of medications, he’s back in good form. It’s a great relief to us all.

He confessed that he’d missed a couple of doses of his Doxycycline, a daily anti-malaria tablet. That’s never good, but it’s a reminder to all of us to be diligent about taking whatever meds we have been prescribed.

I once heard that regardless of whether a person is taking prophylactic (preventative) medication or not, about one in 10 people will get malaria anyway. Ugh.

So yesterday we had another malaria scare or two or three. Adam (our other leader/driver), Thijs and Dee were all feeling poorly and some of their symptoms pointed to malaria.

We arrived in Dalaba, in the Fouta Djalon region of Guinea, in the late afternoon. It has several clinics and a hospital. All three were taken by taxi to a clinic but the doctor was away (or something) and they ended up at the hospital.

Malaria test

At this stage, it seems no one has malaria. but I thought I’d share an exchange between Dee and her brother-in-law. It gives you an idea about the differences between hospitals and medical practices in the West and West Africa.

Dee: Good thing is that I don’t have malaria. Test and advice all for around $25.

Brother-in-law: Dee, these tests have variable sensitivity and specificity. If I were you I would find a doctor and get him to request more appropriate blood tests that include microscopic examination of blood cells, we use the term thin and thick film examination. There should be a reliable laboratory service available somewhere.

Clinic

Dee: Thanks for your advice and I love your optimism re tests etc. The pic shows the room I was assessed in. Did I mention that there was no electricity as the generator didn’t get started until after 6pm and there was no water as the whole town has no water plus the fact that the ‘doctor’ who assessed me had completed three years of his studies and was waiting on money to complete the next three. So as you can gather things are a bit tricky regarding a doctor’s referral etc etc.

Brother-in-law: Wow, I can only begin to understand. The West takes so much for granted.

All photos are by Dee.